Song of the Week: “Square One,” by Coldplay - “Is there anybody out there, who is lost and hurt and lonely, too?”

In 2012, five days after she graduated from Yale University, a talented and thoughtful young woman named Marina Keegan was tragically killed in a car accident. In the wake of her death, the last essay she had written for the Yale Daily News, “The Opposite of Loneliness,” went viral, eventually lending its title to a posthumous collection of the essays and stories she wrote in university.1

That viral essay begins:

We don’t have a word for the opposite of loneliness, but if we did, I could say that’s what I want in life. What I’m grateful and thankful to have found at Yale, and what I’m scared of losing when we wake up tomorrow and leave this place.

It’s not quite love and it’s not quite community; it’s just this feeling that there are people, an abundance of people, who are in this together. Who are on your team. When the check is paid and you stay at the table. When it’s four a.m. and no one goes to bed. That night with the guitar. That night we can’t remember. That time we did, we went, we saw, we laughed, we felt.

After an unusually quiet Christmas break and a solo weekend spent anxious and doom scrolling, this week has been one of the happiest and richest and most energizing weeks I’ve had in a very long time.2 It has been the opposite of loneliness.

On Sunday, I spent 2.5 hours helping my friends Robert and Joe plan their upcoming wedding. On Monday, I spontaneously Facetimed my friend Betta (one of the people who was home sick after NYE) for three hours. On Tuesday, a planned Zoom call with Taylor and Livvy and Ivan lasted till 1 am, and left me buzzing with thoughts and ideas. Last night, I ran an errand with Jillian and then we went out for tacos and talked about everything and nothing until most of the other tables were empty. And today, I spent the afternoon at a work happy hour celebrating a coworker who’s leaving for a new job.3

But all of that somehow paled in comparison to Wednesday: I had four meetings at work, grabbed a quick cup of tea with a friend who was still in town for the holidays, picked up a call from my dad that became a 2.5 hour conversation, and capped it off with a planned call to my old college friend Steve, who I reconnected with at Livvy and Ivan’s anniversary party last month.

I know that many people would be exhausted by that level and intensity of constant conversation - and believe me, this is not what a normal week looks like - but for me, the opposite happened. After each successive conversation, I felt more energized, more optimistic, more secure. It felt like being on a dance floor spinning with a partner, propelled and held up by our own centrifugal force. It felt like hearing voices joining in a chorus.

So anyway, it’s Wednesday night, and I’m sitting at my dining room table watching Steve walk around Manhattan while he tells me about the last decade of his life, which has included time in Cambodia and in Berrien Springs and an MA at Yale Divinity School.4

We talk about his current work as a Seventh-day Adventist chaplain for university students in NYC, and his new Substack, and how jealous I am that he took a class at Yale with Willie James Jennings, whose work made a huge impact on my dissertation.

I am especially curious, however, about his Yale Divinity School application. I’ve applied to sixteen graduate programs over the years, and for me the most challenging part was distilling my interests and experiences and questions into an original, appealing 1-2 page essay that might only receive a minute of a committee’s time. Did he talk about the non-violent resistance he was so interested in when we were students? The work he did in Cambodia?

But instead, he tells me about loneliness.

Epidemic

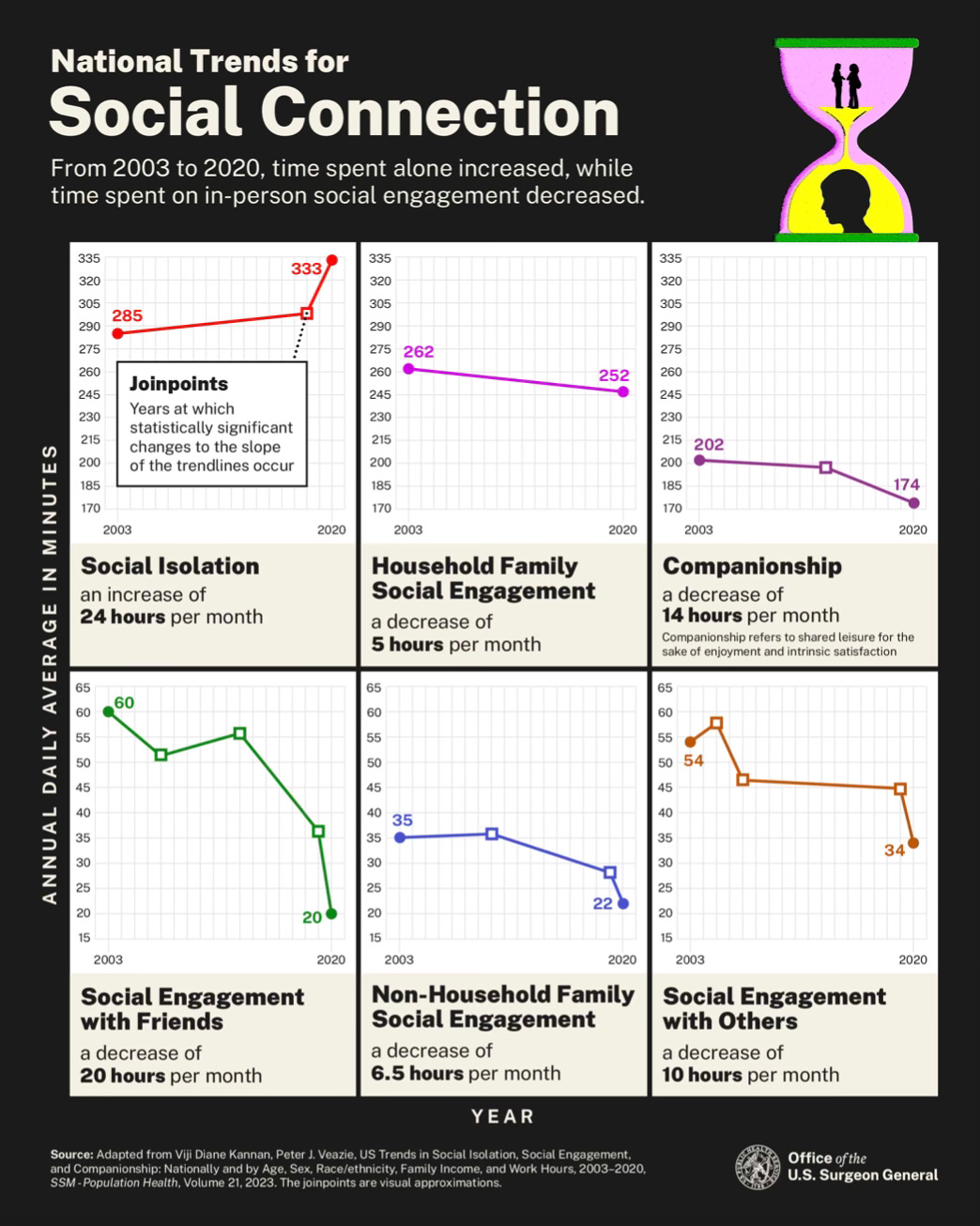

After our conversation, Steve sent me a copy of his personal statement. It opens with a quotation from a 2017 article from the Harvard Business Review by U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy about the American “loneliness epidemic.” Murthy cites research from 2010 indicating that more than 40% of American adults identify as “lonely.” A 2023 Surgeon General’s report demonstrates that things have only gotten worse in the last fourteen years.

By every metric, loneliness is a more pressing problem than it has ever been in modern history. People have less close friends and confidants. They are more likely to move frequently and live farther away from family. They are less likely to trust the people around them or believe that they have much in common. And all of us - not just teenagers - are spending far, far too much time online.

Of course, the pandemic was a deeply lonely time for everyone in the world, forcing us to be apart from most people we loved, as well as losing those small friendly interactions that give life its richness and texture: a compliment from a stranger waiting in line, a joke with a barista, a funny story from your hairdresser.

But most of us are back to our ordinary lives - back to riding transit and going to work and bringing our groceries home without wiping them down with Lysol - and loneliness is still getting worse.

In that report that Steve quoted, Murthy is focused mainly on the health effects of loneliness. In addition to the self-evident mental health impacts - lonely people are far more likely to be anxious, depressed, and antagonistic towards others - loneliness is also linked to numerous physical health conditions. In fact, the research suggests that loneliness has the same negative effects on lifespan as smoking fifteen cigarettes a day!

Murthy is not being glib in referring to it as a public health epidemic. But loneliness is also, I think, an incredibly important factor in the rise of online radicalization and misinformation.

Insiders

A few months ago I watched a documentary about the Flat Earth movement called Behind the Curve. Though the film does feature perspectives from scientists, it doesn’t focus on debunking or mocking what Flat Earthers believe. Instead, it just observes them spending time with each other. They get together for pizza and discussion. They do ill-begotten science experiments to gather proof. The climax of the documentary is an international conference, where local celebrities give talks and people get to hang out with friends they’ve made online.

In an interview with Vice, director Daniel J. Clark explains why he made the rhetorical choices he did when he decided to make a documentary about the movement. “From the beginning, we knew we wanted to not make it a piece that was in any way making fun of Flat Earthers or people with conspiracy theories,” he says. “We knew we wanted to make it a very empathetic movie and understand how and why people might believe this.”

While Clark is very clear that he thinks Flat Earthers are wrong, he also argues that mocking people only causes them to hold more tightly to their beliefs. “The further you antagonize someone, the more secure they become in their position.”

Watching the documentary helped me understand for the first time how people got sucked into a movement like Flat Earth - and why they stayed. To begin with, the average person - regardless of political affiliation or beliefs - is not particularly scientifically literate. Many of the people featured in the documentary, while sweet, were a little awkward or intense. You could see how they had struggled to fit in through the years, how hungry they were for connection.

And then here comes this community that tells them that no, they’re not the weird ones. They’re special and right. Everyone else is wrong, and possibly out to get them. So they push their concerned family away, or they get rejected by them for being “crazy.” And now their only community is this one. And yeah, they spend a lot of time sharing pseudoscientific videos about horizons and shadows. But also, every week, they go out for pizza.5

The Flat Earthers’ beliefs might seem kooky and harmless on the surface (the flat surface), but of course, one does not believe that scientists, government officials, and millions of others are lying to them every day without the erosion of trust in other aspects of their lives. It’s easy to jump from a belief in the Flat Earth to far more sinister beliefs: about medical care, about race, about the necessity of violent action.

I told you, before, about the podcast Rabbit Hole, which looks at the ways that YouTube frequently serves as a gateway to online radicalization. While the podcast examines several individuals and subcultures, I was struck by the fact that all of them were united by intense social isolation and desperate loneliness.

The main subject of the podcast is a young man who was watching YouTube 14 to 16 hours a day. Gradually, his YouTube algorithm - which began with videos about self-help and exercise - fed him more and more radical videos until one day it gave him explicit neo-Nazi recruitment materials. He was lonely, and angry, and wanted to know why his life didn’t feel successful or fulfilling, and they gave him a simple narrative and a villain to blame.

A few episodes later, Rabbit Hole profiled a group of QAnon conspiracy theorists. Without fail, all of them started in a place of loneliness: following a move, or a loss, or resulting from a persistent awkwardness and difficulty fitting in.6

I had generally thought about QAnon followers up to this point with a mixture of disgust and disdain, but I had never heard a recording of them talking before. The journalists included a recording of a weekly video call where the participants chatted about their recent theories and “discoveries.” Mixed in among discussions of blood drinking and secret cabals, however, were achingly normal little interactions.

Participants in the call - many of them older - used expressions like “yabba dabba doo” and “fuzz my butt.” One man stopped mid “analysis” of a message from Q to return a text because “I try to always respond to my wife.”

“What was going on inside these QAnon Facebook groups,” says host Kevin Roose, “like, all this constant commenting and liking and sharing: these actual friends were forming. It was meaningful social interaction.” And so well-meaning, dorky people end up believing and acting on deeply sinister and antisocial ideas, because it makes them feel a little less alone.

We are pack animals, and we desperately want to belong to a pack. Unfortunately, for so many people, the belonging quickly becomes more important than what that pack does.

Curing the Terrible Disease

In 1974, the American writer Kurt Vonnegut gave the commencement address at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Vonnegut - often considered one of the greatest American writers of the twentieth century - was at the height of his career. He was 51 years old, and had published his most famous novel, Slaughterhouse-Five, five years before to enormous success.

And yet, when asked to give the commencement address at this elite institution, the focus of his speech was much the same as the editorial that young Marina Keegan would write to celebrate her graduation decades later.

Though Vonnegut talks about a lot of other things - communism, the environment, scientific progress - the core of his message is this: “What should young people do with their lives today?” he asks. “Many things, obviously. But the most daring thing is to create stable communities in which the terrible disease of loneliness can be cured.”

For my friend Steve, writing that essay for his application to Yale, the daring thing to believe in was church. “”In wondering what the Church can contribute to American society - how it can really help - the stickiest answer, to me, is healing our loneliness,” he wrote. “The Church, functioning properly, excels at this.”

That “functioning properly,” of course, is vital. Many people have been hurt by churches, or been told “all are welcome” and then discovered that invitation came with a heteronormative asterisk. And many people will never feel comfortable or safe inside a church’s walls. But it is still a helpful antecedent.

When my friends Livvy and Ivan first moved to Boston, they complained to a new acquaintance that they felt like they weren’t being invited along to things. “What things?” the woman replied. “None of us are doing anything.”

So they decided to start doing things themselves. Taking inspiration from the dinners of our Adventist childhoods, they began hosting a weekly Friday night dinner party called “Sabbath Dinner” where they shared simple food with guests, lit candles, and led structured reflections on the good and hard things that had happened that week, as well as the things they anticipated in the week ahead. And they invited people from throughout their lives - people from work, and from the climbing gym, and later, people they met on the elevator of their apartment building in Denver. When we lived in Colorado, we’d make the trek down to Denver from the Boulder area, and spend a couple of hours eating cinnamon buns and letting the weight slide off our shoulders and opening our hearts to strangers whose faces were made soft and warm by candlelight.

The work that Vonnegut describes - the work of treating the terrible disease of loneliness - isn’t easy. It’s vulnerable and awkward and sometimes it works, and sometimes it just struggles along. The first time Livvy and Ivan tried to host a potluck in Boston, they made baked potatoes for twenty people and then no one showed up.

But you can start small. You don’t have to throw a party or complete a weeklong marathon of phone conversations. You can spend less time watching other people live seemingly glamorous lives on Instagram, less time sucked into Reddit threads about how everyone who doesn’t agree with you is a monster and we’re all doomed, and more time just existing in your community. You can sign up for a workshop at your local library, or join a knitting group, or make small talk with the old folks on the elevator in your building. You can practice trying to love your neighbor - your real neighbor, the one across the street or down the hall - as yourself.

Willie James Jennings - the theologian Steve took classes with that I love so much - wrote a book called After Whiteness, which works to imagine what education might look like if extricated from the historical forces of white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalism. At its best, he argues, educational spaces are places for intellectual communion. “And in [such] thinking together,” he writes, “we begin to see what we had not seen before: we belong to each other, we belong together. Belonging must be the hermeneutic starting point from which we think the social, the political, the individual, the ecclesial, and most crucial for this work, the educational.”

Belonging: not to an “us,” opposed to a “them,” but simply to each other. Flawed, strange, awkward, human, and imbued with inherent worth. We have to be there for each other. It is the only cure for the terrible disease of loneliness.

When it comes to loneliness, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

I skimmed through the entire collection once, and at the risk of sounding like a terrible person, I was underwhelmed. There are flashes of brilliance, but mostly I was left frustrated and sad that this clearly sincere and talented young woman never got to hone her craft and mature as a writer.

Taylor is in the process of renewing his passport, which - even expedited - means he can’t cross the border for at least 2-3 weeks. Also, every participant at that New Year’s Eve party last week except for me immediately got sick after, so social plans were thin on the ground around here for a bit.

Unsurprisingly, the week I just described is also why today’s Syllabus is setting a new record for lateness.

It is a weird coincidence, I swear, that both of these stories involve Yale. I suppose once you reach a certain critical mass of socializing for a week parallels and connections are bound to occur, kind of like how if a group of any random fifty people are brought together there is a nearly 100% chance that two of them will share the same birthday.

In an episode of the podcast Oh No! Ross and Carrie, which examines pseudoscientific conspiracies and fringe beliefs, a group of Flat Earthers joke that they love pizza because it represents the true shape of the earth.

A few years ago, I had an Uber driver who spent the entire drive telling me QAnon conspiracy theories. Near the end of the conversation, I discovered - to my complete lack of surprise - that this kind-faced older man’s wife of more than thirty years had died suddenly a few months earlier.

Absolutely spot on! With your permission, I’m going to share this with a bunch of my friends here in Anacortes. We’ve been talking about how to reach out to the lonely in our community. It is truly an epidemic.