“What Are You Doing New Year’s Eve?” by Ella Fitzgerald - “Wonder whose arms will hold you good and tight / When it's exactly twelve o'clock that night”

This past Tuesday night, I celebrated New Year’s Eve in the same place I did the previous two years: The Adventurer’s Guild, a Dungeons and Dragons-themed board game café here in Kitchener. In the hours leading up to midnight, my friends and I laughed over silly party games, shared platters of nachos, and ordered drinks with names like “The Jean-Luc” and “The Whiskey Sauron.” 1

At midnight, however, our celebration took the same shape as it has nearly every year of our adult lives: we counted down to midnight, yelled “Happy New Year!”, kissed, toasted with bubbly, and muddled our way through the first verse of “Auld Lang Syne.”

I can’t tell you where I spent most Easters or Thanksgivings of the past fifteen years, but every New Year’s stands out, despite the repetition. There’s the night we braved a snowstorm to watch the fireworks from Livvy and Ivan’s high-rise apartment in downtown Denver. The time we donned sequins and lipstick to sit on our pandemic pod buddies’ couch in 2020, the same way we had nearly every weekend that year. Or the year when Jillian and I rang in the new year five hours ahead of our families, at a neighborhood pub in London while on a backpacking trip through the UK.

Perhaps it’s because of the holiday’s insistence on happening at an exact time. You can celebrate Christmas with family a week early or late if schedules and circumstances require it, but no one is counting down to midnight on January 5th.

Or perhaps it’s because New Year’s Eve feels more international than any country’s independence day, more inclusive than a holiday with religious origins. We are all here together, on the same planet, moving through time.

Or perhaps it’s because New Year’s Eve is our only major holiday of the threshold: the finale of one year, the cusp of the next.

By this point, the traditions of New Year’s Eve are so familiar that - much like the passing of time from one year to another - they feel inevitable.

But, of course, that wasn’t always the case.

The God of Doorways

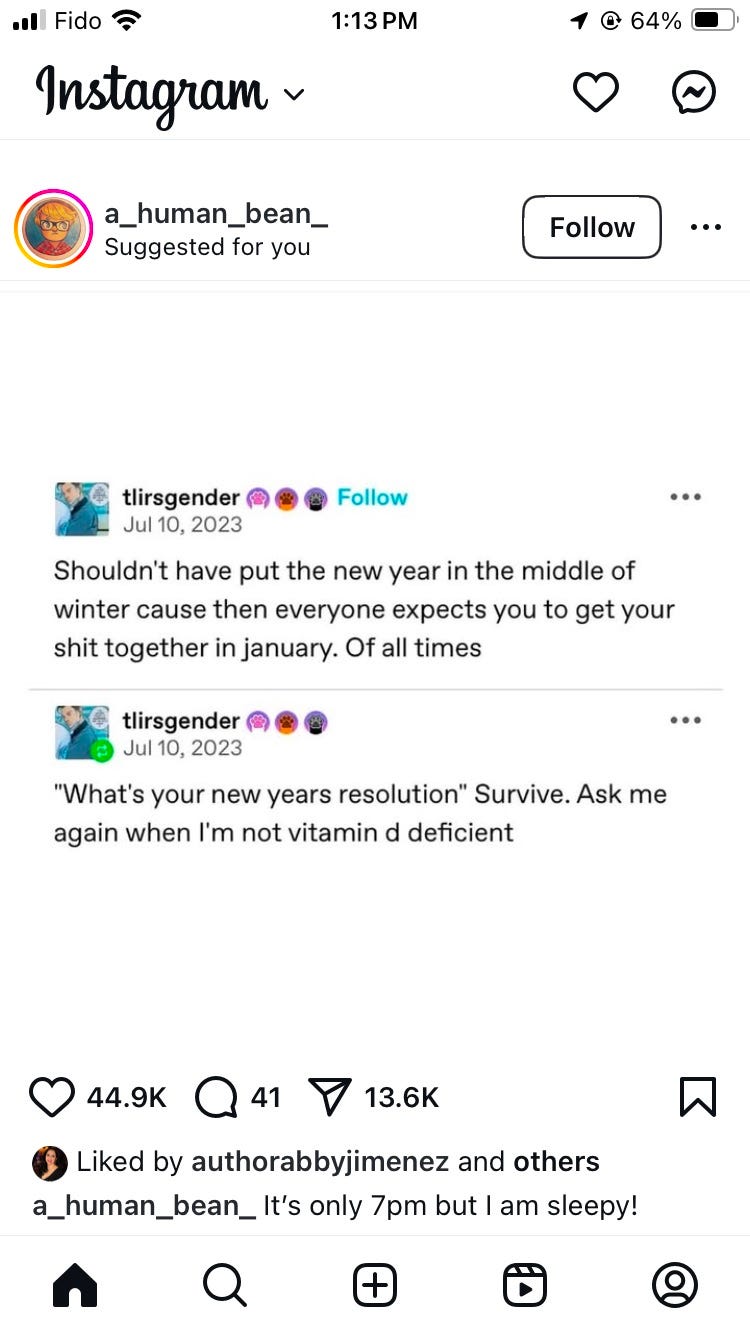

Every year, like clockwork, social media is filled with posts by people complaining that the new year starts in January. Take, for example, this one that popped up in my feed this week.

After all, despite the fact that the entire world recognizes the Gregorian calendar that runs from January to December, other cultures celebrate their traditional new years at other points in their seasonal cycles. Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, takes place in late summer or early autumn in the Northern Hemisphere. Chinese New Year, which marks the end of winter and the beginning of spring, is celebrated in conjunction with the new moon that appears between January 21 and February 20.

So why is New Year’s Eve December 31st? Why not ten days earlier, to mark the winter solstice and the return of the sun? Why does the new year not begin with the return of spring (as it does in Stardew Valley)?

The short answer? We’re not sure.2

Though the Gregorian calendar was established in 1582, it mostly adjusted for an incorrect calculation in regards to year length and leap years. The Gregorian calendar employed the same order and structure of months as the Julian, or Roman, calendar.

Some of our months still bear their Latin names in English: September (7), October (8), November (9), and December (10). Others are derivations of the original Latin: March comes from “Martius,” named for Mars the god of war, and January from “Januarius,” named for Janus, the two-faced god of doorways and beginnings.

When Julius Caesar established the Julian calendar in 45 B.C.., standardizing the lengths of the months and accounting for leap years, he maintained the existing Roman tradition of the year beginning in January. The ancient Romans of the time, however, were unclear as to why the year started then. As historian Denis Feeney writes in Caesar’s Calendar: Ancient Time and the Beginning of History, “The Romans themselves were not sure why their civil year began in January, and the names of the months after June (going from Sextilis to December) made it easy for them to imagine that originally their calendar and civil year must have begun at the more ‘natural’ beginning time of the spring, with March as the first month” (204).

The Romans and their contemporaries had various stories explaining why the calendar began in January, attributing it to the legendary king Numa Pompilius (successor of Romulus), to the government of the Second Decemvirate, or to a 3rd century magistrate who published the calendar in the Forum. Many explanations pointed to Janus’s status as God of beginnings, or the proximity to the winter solstice, but these were introduced to explain an existing tradition, not to justify a new change.

Regardless, much like today’s social media posters, the Romans seemed a little bummed that they were ringing in the New Year in the middle of a cold and dark season.

The Roman poet Ovid, for example, begins his Fasti with a question addressed directly to the god Janus: “Please tell me why the New Year begins with frosts, when it should better have begun with spring?”

Dropping the Ball

When I was a kid, celebrating New Year’s Eve at my Aunt Rosemary’s house - in an era before smartphones and easily coordinated world clocks - we always watched the ball drop in Times Square on TV. While cities around the world have their own high-profile New Year’s parties - I spontaneously spent a memorable NYE with my brother and my cousin freezing in the crowd at one in Niagara Falls - New York City is the gold standard.

An estimated one million people gather in and around Times Square every year to listen to performances by popular musicians, dance, and hopefully kiss their sweetheart on live TV.3

Since 1991, balloon designer Treb Heining has led a team of one hundred volunteers in dropping over 3,000 pounds of custom made, biodegradable confetti from surrounding buildings into the square.

And - of course - at exactly 11:59:00 p.m., a glittering ball begins to descend a pole to usher in the new year.

In 1904, the New York Times moved to its current office location in what became known as Times Square. Newspaper owner Adolph Ochs invited citizens to celebrate New Year’s Eve in front of the fancy new headquarters by putting on a dramatic fireworks display at midnight. After a couple of years of this, however, the city banned his fireworks show as a hazard, so he responded with a new plan: a dramatically lit ball illuminated with electric lights would descend a pole at midnight instead.

The first ball drop was on December 31, 1907, and has taken place every year since except for 1942 and 1943 (due to wartime blackouts). The ball itself has changed style (and added glitz) several times over the years, and is often engraved with wishes for the new year, or remembrances of the past one. On December 31, 2001, for example, 195 of the 504 crystal facets of the “Hope for Healing” ball were engraved with “the names of the countries and regions that lost citizens, the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, the four airline flights and the names of uniformed rescue organizations that lost members in the 9/11 tragedy.”

It might surprise you, however, to discover that Adolph Ochs did not invent the ball drop. Rather, he was drawing on an archaic form of time keeping with naval origins. In the nineteenth century, countries around the world commonly used “time balls” perched in easily visible places to signal to nearby ships the exact time. The first and most prominent of these was the bright red Time Ball atop the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England. Beginning in 1833 - and continuing to this day! - the red ball would climb to the top of a pole at 12:55 p.m. and then descend precisely at 1:00 p.m., allowing ship captains on the River Thames to adjust their chronometers accordingly.

Today, however, most people seem to associate New Year’s Eve more with the drop than with the ball, as evidenced by this incredible Wikipedia list of various items dropped in communities around the world. Though it contains many gems - Tallapoosa, Georgia, for example, lowers a stuffed opossum named Spencer - my favorite is one that Taylor remembers personally.

In Plymouth, Wisconsin, less than twenty minutes from where he grew up, they drop - what else? - a wedge of cheese.4

Fondly Kissing

It’s easy to forget, as I look forward to celebrating ten years (!) with Taylor this year, that New Year’s Eve used to make me feel almost as lonely as Valentine’s Day. The new year, after all, is punctuated not only with a cheer but with a kiss, as illustrated memorably in this scene from Friends:

While kissing at midnight doesn’t have to be romantic, not having someone to kiss in a room full of couples can be terribly lonely. That’s the reason why, at the end of my favorite romcom When Harry Met Sally, Sally wants to go home early. And that’s partially why Harry’s midnight declaration of love and accompanying kiss is such a perfect end to the film.

Much like the New Year beginning in January, we don’t know why we kiss at New Year’s - but we probably got it from the Romans. Most contemporary articles investigating the subject point to Saturnalia - the Roman winter festival of celebration and debauchery - as the predecessor of the drunken revels that so often mark New Year’s Eve. And, much like the Times Square ball drop, the modern tradition of kissing on New Year’s first appears in New York. According to an 1863 New York Times article, the tradition of kissing at midnight was introduced by German immigrants:

As the clocks ring out the hour of midnight, all this festivity pauses for a moment, to listen, and as the last stroke dies into silence, all big and little, old and young, male and female, push into each other's arms, and hearty kisses go round like rolls of labial musketry, with the exclamation "Prost's Neujahr!" (Hail the New-Year!) Gentlemen and ladies in the bloom of youth heartily approve this custom, and their venerable predecessors likewise seem to relish it, if 'twere only for the sake of "Auld Lang Syne!"

I find it fascinating that this 1863 article connects the New Year’s Eve kiss to “Auld Lang Syne,” because When Harry Met Sally does the same thing. Right after he and Sally kiss, Harry launches into one of his characteristic rambles.

“What does this song mean? My whole life, I don’t know what this song means. I mean, ‘Should old acquaintance be forgot.’ Does that mean that we should forget old acquaintances? Or does it mean that if we happen to forget them, we should remember them, which is not possible because we already forgot ‘em?” Sally just smiles and shakes her head, indulging him. “Anyway,” she concludes, “it’s about old friends.”

What Sally had forgotten, feeling single and lonely on New Year’s - and what I forgot all those years as well - is something that those German immigrants remembered. New Year’s doesn’t have to focus on midnight romance. It can just be about being with people you love.

Auld Lang Syne

I have one more unofficial New Year’s tradition, one that is far less common. Every new year since December 2019, either in the waning hours of December or the first couple of days of January, I listen to the “Auld Lang Syne” episode of The Anthropocene Reviewed.

As John Green explains, Auld Lang Syne is a very old song - a peculiar and fitting thing to sing every year as we welcome in the future. The first draft of its modern lyrics were scrawled in a 1788 letter by the Scottish poet Robbie Burns, writing to his friend Frances Dunlop. But we know that the first verse - “Should old acquaintance be forgot / And never brought to mind? / Should old acquaintance be forgot / And auld lang syne” - is at least 400 years old. Indeed, Burns - who today is credited with at least three of the song’s verses - later said that he “took it down from an old man.”

The song’s title comes from a Scots phrase that literally translates to “old long since,” but is better understood as “for old time’s sake.” In other words - we sing “Auld Lang Syne” because we see no more fitting way to welcome a new year than by honoring the ones that have come before.

For Green, that means remembering his friend Amy Krouse Rosenthal, a writer who died of ovarian cancer in 2017. She is one of the people he thinks of, he explains, when he recalls the third (usually unsung) verse of “Auld Lang Syne”: “We two have paddled in the stream, from morning sun till dine, but seas between us broad have roared since Auld Lang Syne.”

…I think about the many broad seas that have roared between me and the past--seas of neglect, seas of time, seas of death. I’ll never speak again to many of the people who loved me into this moment, just as you will never speak to many of the people who loved you into your now. And so we raise a glass to them--and hope that perhaps somewhere, they are raising a glass to us.

I will leave Green’s beautiful and grief-filled reflections on his friend for you to discover for yourself; suffice to say, I do not cry annually to this essay because of my deep and abiding love for etymology. But I want to tell you about the ending.

During World War I, he explains, exhausted and cynical soldiers turned the tune of “Auld Lang Syne” into an absurdist song about the futility of their suffering. “We’re here because we’re here because we’re here,” they would sing.

Sometimes, in events she organized, his friend Amy would ask the audience to sing that lament with her, transforming its meaning without changing a word.

And although it is, of course, a profoundly nihilistic song written about the modernist hell of repetition, singing that song with Amy, I could always see the hope in it. It became a statement that we are here--meaning that we are together, and not alone. And it’s also a statement that we are, that we exist, and it’s a statement that we are here, that a series of astonishing unlikelihoods has made us possible and here possible. We might never know why we are here, but we can still proclaim in hope that we are here. I don’t think such hope is foolish or idealistic or misguided. I believe that hope is, for lack of a better word, true.

And then Green invites his listener to sing with him, and he begins to sing, waveringly, in a quiet and reedy voice. And, through my tears, I always sing quietly with him.

I only have one resolution this year, a year already tinged with anxiety and disappointment and separation: I want to send birthday cards to all of my friends. Because I am so thankful that I continue to be here, and that they are here also, and despite the fact that “seas between us broad have roared,” I remember with gratitude all the ways that they have loved me into this moment.

Happy New Year. I’m so glad we’re here, together, too.

When it comes to New Year’s Eve, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

The Jean-Luc includes Earl Grey tea, and the Whiskey Sauron is topped with a fiery eye made out of a lemon slice and a maraschino cherry

Kudos to redditor WelfOnTheShelf,who saved me a lot of the legwork on this research.

If the crowd alone isn’t enough to deter you, consider this: participants aren’t allowed to drink alcohol or carry backpacks, the temperature is an average of 34 F/1 C, and people frequently wear adult diapers because they have to stand in place for hours without being able to use the bathroom

Bafflingly, at 10 p.m., to “keep the event family friendly.” As a result - as seen in this video - when the cheese wedge reaches the ground people mostly just yell indiscriminately.

Your New Year’s Eve traditions sound meaningful. I don’t celebrate unless I have others to celebrate with. Getting old and stodgy I guess.