Song of the Week: “Library Magic,” by The Head and the Heart - “I'm just glad to go through it all with you as a friend.”

I don’t remember a time before I loved the library.

Some of my earliest memories are of going to the public library in London, Ontario, with my mother. It was a marvelous library, filled not only with books, CDs, and VHSs, but also with musical instruments, tools, and toys that patrons could check out. My mom, who had her hands full running a home daycare and taking care of my newborn brother, would check out videos for me about world folklore or how baby animals grew, and I spent hours enthralled learning about the amazing world around me. I thought the intro to the Eyewitness videos was the coolest thing I had ever seen.1

A year later, in first grade, our teacher was having our whole one-room school “read around the solar system.” The goal was to read nine chapter books, one for each planet on the bulletin board, and then receive a prize at the end. At the beginning, I confirmed with my teacher that if I completed the solar system multiple times I would receive multiple prizes, and I was off to the races.

With a love for a challenge that continues to this day, I read stack after stack of chapter books from the library, looping through the solar system four or five times and endangering my teacher’s stash of stickers, bouncy balls, and other coveted treasures.

Throughout elementary and high school, the library was my second home. I got my first library card of my own at age seven, on a field trip to the delightfully-named Terryberry branch of the Hamilton Public Library. When the beautiful Caledonia Public Library re-opened in a new community center a few blocks from my house, it was the first place I learned to walk to alone.

Throughout my childhood, my voracious appetite for books was more than my parents could have ever kept up with financially: I often read ten or fifteen books a week. Thanks to the library, I could feed my endless hunger, devouring junk food like The Babysitter’s Club and The Boxcar Children a shelf at a time while also eventually falling in love with incredible authors like Cornelia Funke and Terry Pratchett.2

Some of my favorite memories are of the nights when, because my dad had a late meeting or church visit and couldn’t join us for dinner, my mom, brother, and I would have “reading suppers.” After school, we’d stop at the library and each of us would take our time browsing through the stacks until we’d picked out a pile of books that had caught our interest. In the car, we’d show off our finds to each other, then back at home we would eat our dinner in companionable silence while reading, the kitchen silent except for the scrape of our forks and the gentle susurrus of turning pages.

Decades later, despite building a large home library of my own, my love for public libraries has not waned.

When I was working as a tutor, I checked out audiobooks on CD and listened to novels about Shakespeare and baseball and growing up queer and Latino while driving all over the city. During the pandemic, I finally and begrudgingly fell in love with ebooks thanks to the Boulder Public Library’s enrollment in the Libby app, and spent hours escaping into fantasy and romance novels without having to leave the house.3

And today, I visit the wonderful Kitchener Public Library several times a month, to research my family history in the archives section, to get an iced latte or vegan sausage roll from the in-house cafe, to check out an old BBC series on DVD, or - of course - to do research for the next issue of Syllabus.

My entire life is a testament to what PBS’s Arthur told me all those years ago, during that second-grade field trip to the library: having fun isn’t hard when you’ve got a library card!

Instructive to the Community

While people and institutions have been amassing private collections of books for as long as there have been books, public libraries are a relatively new development.4

While there are isolated instances of churches, universities, or governments making archives and book collections available to the public since at least 1400, libraries as we know them today did not exist until the mid-nineteenth century. These libraries - publicly funded and available to everyone - emerged in tandem with the Industrial Revolution, as societal reformers advocated for the rights and education of workers.

English working class advocate Francis Place, for example, campaigned for “the establishment of parish libraries and district reading rooms, and popular lectures on subjects both entertaining and instructive to the community might draw off a number of those who now frequent public houses for the sole enjoyment they afford.”

While communities around the world gradually introduced library collections, allowing books to circulate and dramatically improving literacy and access to knowledge, one person stands out as instrumental in the history of public libraries: Scottish-American steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie.

Though Carnegie became one of the wealthiest men in the world because of greed, exploitation, and industrial monopolies, he is mostly remembered today as a philanthropist: in the last 18 years of his life, he gave away more than 90% of his fortune, the equivalent of $6.5 billion today.5

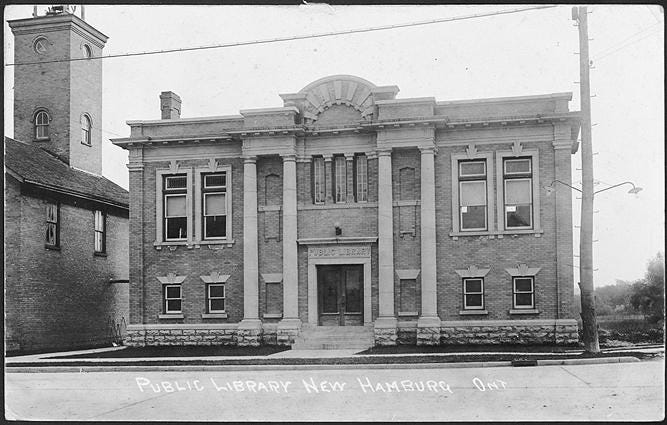

In addition to funding iconic buildings like Carnegie Hall and sponsoring 7,000 church organs, Carnegie and his foundation built 2,509 libraries between 1883 and 1929: 1,689 in the United States, 660 in the United Kingdom and Ireland, 125 in Canada, and 25 more in Australia, South Africa, New Zealand, Serbia, Belgium, France, the Caribbean, Mauritius, Malaysia, and Fiji.6

By the time Carnegie died in 1919, almost half of the United States’s 3,500 libraries were Carnegie libraries.

Carnegie specifically funded libraries because he believed that free and open access to information was essential for people to improve their lives and be good citizens. While their architecture varied in accordance with local preferences, the libraries shared a few common features reflective of Carnegie’s beliefs: there would be a grand doorway at the top of a staircase to represent the elevation provided by learning, and a lamp post near the entrance to represent enlightenment.

Carnegie’s libraries also had practical features that set them apart. His libraries were the first to include dedicated spaces for children as a matter of course. The donations also included a provision insisting on public support: cities had to pledge to contribute ten percent of the building cost per year to the library to pay for personnel, collection growth, and other operating expenses. Finally, Carnegie’s libraries had to be open to the public without requiring any kind of paid subscription beyond taxes, to ensure that they were accessible to everyone.7

As Patricia Lowry writes, "To this day, Carnegie's free-to-the-people libraries remain Pittsburgh's most significant cultural export, a gift that has shaped the minds and lives of millions."

The Room of Requirement

Today, public libraries are both ordinary and ubiquitous, something we often take for granted. It is easy to lose sight of what an incredible gift they are to all of us: as community gathering places, literal shelters from the storm for the housed and unhoused alike, workshops for creativity and technological literacy and citizenship and genealogy, and treasure troves of knowledge both general and deeply specific. As Albert Lee tweeted in 2020, “If public libraries were invented today, they’d be decried as radically socialist, economically unfeasible, and the certain end of the book publishing industry.”

Indeed, as Detroit librarian Annie Spence reflects at the beginning of the wonderful This American Life podcast episode “The Room of the Requirement,” public libraries are unique among contemporary institutions:

I always say that it’s the only place - well, it’s one of the last places you can go that you don’t have to buy or believe in anything to come in. You can just come, and we’ll help you, no matter what your question is. We’ll try to figure it out with you.’

While “The Room of Requirement” tells several wonderful stories about public libraries, my favorite is the one shared by Lydia Sigwarth.

When Sigwarth was a child growing up in Dubuque, Iowa, she and her family were temporarily homeless because her parents couldn’t find a place they could afford to house all nine members of their family. To escape the cramped family member’s basement where all of them were living together, Sigwarth’s mother would take the kids to the public library for hours every day, to give them their own space to relax and explore.

“I remembered that time so fondly, that I was like, oh, that was the year we lived in the library,” Sigwarth reflects. “It was the best time ever. I just remember the feeling that it gave me, of belonging.” Years later, as part of the episode, the This American Life staff reconnected Sigwarth with Mrs. S(tephenson), the children’s librarian that made her feel so special and cared for when her family was going through a hard time.

“This was my home for that year, and I felt like I belonged. I belonged, and I was safe here,” Sigwarth tells Mrs. Stephenson. Though the older woman is gracious about the praise, she also insists that she did not do anything exceptional. “It’s everyday life for the library…It’s what we do.”

It is also what Lydia Sigwarth herself does every day today too: she became a children’s librarian herself, and provides a safe and welcoming space for families like her own at the library in Platteville, Wisconsin.

Under Attack

Public libraries are, in many ways, at the center of community and democracy.

They welcome immigrants and language learners, help people find jobs and do their taxes, and teach basic life skills like budgeting, cooking, and home repairs. They provide social events for senior citizens and story time for babies and kids. In library maker spaces like the one at my local library, anyone can play musical instruments or use a recording studio, 3-D print and laser cut, use a sewing machine or design a t-shirt. Librarians answer questions both mundane and profound, help connect people with social services, and cultivate a love of learning in the next generation.

As this video from the Harris County Public Library demonstrates, in a parody of comedian of Bo Burnham’s “Welcome to the Internet,” librarians offer their communities “a little bit of everything all of the time.”

More, perhaps, than any other modern institution, public libraries protect citizens’ right to access information, to ask questions, and to learn without judgment or censorship. This mission is so important that, since 1939, the American Library Association has continually affirmed it in the Library Bill of Rights:

The American Library Association affirms that all libraries are forums for information and ideas, and that the following basic policies should guide their services.

I. Books and other library resources should be provided for the interest, information, and enlightenment of all people of the community the library serves. Materials should not be excluded because of the origin, background, or views of those contributing to their creation.

II. Libraries should provide materials and information presenting all points of view on current and historical issues. Materials should not be proscribed or removed because of partisan or doctrinal disapproval.

III. Libraries should challenge censorship in the fulfillment of their responsibility to provide information and enlightenment.

IV. Libraries should cooperate with all persons and groups concerned with resisting abridgment of free expression and free access to ideas.

V. A person’s right to use a library should not be denied or abridged because of origin, age, background, or views.

VI. Libraries which make exhibit spaces and meeting rooms available to the public they serve should make such facilities available on an equitable basis, regardless of the beliefs or affiliations of individuals or groups requesting their use.

VII. All people, regardless of origin, age, background, or views, possess a right to privacy and confidentiality in their library use. Libraries should advocate for, educate about, and protect people’s privacy, safeguarding all library use data, including personally identifiable information.

Libraries are so important to maintaining freedom of thought and freedom of access that it should, perhaps, not surprise us that they are continually under threat. Despite the fact that libraries are enormously popular - American libraries have more than four million visitors per day - they are constantly under threat.

In a recent high profile struggle, the New York City government announced dramatic budget cuts to the New York Public Library system. The NYPL is the largest public library system in North America, with 92 locations and more than 18 million visitors a year. The cut would reduce much of the New York Public Library’s children’s programming - much of which reaches low-income, immigrant, and homeless children, as well as forcing the closure of libraries throughout the city every Sunday. After a months’ long struggle and support campaign by friends of the library, the $58.3 million cut was restored, allowing the NYPL to return to normal operation.

Other attacks on public libraries are more sinister. As John Oliver explains in this episode of Last Week Tonight about public libraries, local and state governments around the country have been passing laws restricting the freedoms of public libraries and their patrons, as part of large book-banning efforts by self-appointed moral guardians.

As Oliver notes, in 2023 the ALA documented attempts to censor or ban over 4,200 separate books at public libraries, an increase of 92% from the previous year. Nowhere have those recent book banning attempts been more high profile - or more successful - than in Idaho.

The recently passed House Bill 710 requires moving materials deemed “harmful to minors” to “ a section designated for adults only.” If libraries don’t comply with the ban - which could be interpreted to include materials including books about human biology, sexual education, and LGBTQ+ issues for readers as old as 17 - they will face a $250 fine per challenged book.

To make matters worse, many small libraries - much like the one in Mt. Hope that I frequented as a kid - only have one large public-facing room to house their entire collections. Because the Idaho law requires that these so-called harmful materials be kept in a separate room behind a closed door, small libraries are faced with a decision between risking spending their limited operating budgets if they’re fined, or getting rid of their children’s and young adult collections and programming completely and making entire library branches adults-only.

Even when libraries do have the room and resources to comply with the law, the results can be patently absurd.

As Idaho resident Carly explains in this recent TikTok video, her daughter Scarlett recently read and loved Tolkien’s The Hobbit, and wanted to read The Lord of the Rings next.

When they went upstairs to pick up a copy of The Fellowship of the Ring, however, they discovered that it was shelved in a restricted adults-only section, and that Scarlett couldn’t pick the book up without having a signed affidavit from her mother. When Carly went to follow her daughter to the stacks, however, the librarian on duty stopped her: Carly was holding her one year-old baby, Daphne. Did the baby have a library card? No, Carly said, Daphne couldn’t even sign her own name, let alone read. Then, said the embarrassed librarian, Carly couldn’t bring her into the stacks without filling out even more paperwork because the baby was a minor.

“Mostly,” Carly concludes, “my heart broke, because what about these kids that aren’t coming in with parents? What about the Matildas out there…what about the Hermiones out there? I’m shocked that we are doing this, Idaho. It’s depressing.”

The Library Book

I could fill a library of my own with stories about the good public libraries do, and the ways that they have provided both jumping off points and safe places to land for countless impactful people throughout history. If you consume only one piece of media about public libraries, however, it should be Susan Orlean’s incredible 2018 book The Library Book.8

Orlean’s book is equal parts true crime and history of the public library: at its centerpiece is the 1986 arson of the central branch of the Los Angeles Public Library. The fire, which burned for more than seven hours and destroyed more than one million books, remains the largest library fire in American history.

As she investigates the mystery of how and why the arson happened, Orlean also uses the 1986 library fire as a lens, through which readers encounter a kaleidoscope of stories about the past, present, and future of public libraries both in the United States and abroad. We learn about the larger-than-life characters who battled for control of the LA Public Library; the melancholy poetry written by librarians in the months following the fire; and the ways in which modern libraries have expanded their offerings to include free WiFi, ebooks and audiobooks, and community services.

It is this passage near the end of the book, however, about the more than 320,000 public libraries worldwide, that moved me to tears:

A large number of these libraries are in conventional buildings. Others are mobile and, depending on the location’s terrain and weather, operate by bicycle, backpack, helicopter, boat, train, motorcycle, ox, donkey, elephant, camel, truck, bus, or horse. In Zambia, a four-ton truck of books travels a regular route through rural areas. In Cajamarca Province, Peru, there is no library building, so seven hundred farmers make space in their homes, each one housing a section of the town library. In Beijing, about a third of library books are borrowed out of vending machines around the city. In Bangkok, a train filled with books, called the Library Train for Young People, serves homeless children, who often live in encampments near train stations. In Norway, villages in the fjords without libraries are served by a book boat that makes stops along the coast of Hordaland, Møre og Romsdal, and Sogn og Fjordane counties all winter. (291)

All those people around the globe, doing whatever it takes to read to their kids and escape into stories and learn more about the world around them.

All those readers as hungry for books as I have always been.

All those librarians overcoming incredible odds to bring them what they need.

When it comes to public libraries, what else should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

It’s still pretty high up there.

Despite The Babysitter’s Club being repetitive fluff, it had its important moments, and I truly love the updated Netflix adaptation, which is charming, funny, and worth watching for audiences of all ages.

Libby is a service that more than 90% of North American libraries use, providing library patrons with access to hundreds of thousands of ebooks, audiobooks, and periodicals. It is particularly wonderful because it allows you to link several library cards to your account at the same time, and cross-reference your searches across your available cards.

Indeed, long before there have been books: archaeologists have discovered collections of clay tablets in ancient Sumerian temples, and the famed Library of Alexandria’s collection consisted almost entirely of scrolls

The real question is how we can bully billionaires today into using their money to eradicate child poverty or fund arts programs instead of ruining social media platforms and attempting to colonize the Moon.

Some of these were university libraries, but the vast majority were public libraries.

“Accessible to everyone,” however, often came with an asterisk: for a large portion of American history, libraries - like most other public spaces - were segregated according to race. Rather than force desegregation, Carnegie simply provided funding for libraries specifically for Black people.

Orlean is most well-known for her 1998 book The Orchid Thief, which was adapted into the 2002 Nicholas Cage film Adaptation.

Libraries are the best! I always recommend them to everyone as a great resource and am surprised how many people don't take advantage of their services.

I too love libraries! I’ve just recently discovered that our library lets you take out a day pass to any provincial park.