Song of the Week: “knitting song,” by Paris Paloma - “Simple entwining of intimate string / It‘s a beautiful thing”

I thought I knew how to knit.

As I talked about briefly last month, I’ve been knitting since I was thirteen. I’ve made socks and mittens, pulled off cables and fair colorwork. Almost every Christmas someone on my list gets a handmade hat.

Ever since I started going to my knitting circle, however, I’ve felt like a first grader trying to fit in with university students.

Last month, a little yarn store (LYS) called The Flying Squirrel opened in downtown Waterloo, just a few doors down from my favorite specialty grocery store, Vincenzo’s. They announced that they would be hosting a free knitting and crocheting circle every Thursday night from 6-8 pm, everyone welcome.

So three weeks ago I showed up, with an unfinished sweater I started during the pandemic in tow, and was immediately overwhelmed. Despite the fact that the shop was less than a month old, everyone seemed to know each other, and had attended the same local fiber festivals and knitting groups for years.

Half of the people were wearing beautiful lace shawls or elaborate sweaters, and I suddenly felt very silly clutching my plain boxy sweater full of obvious mistakes.

I thought I knew all of the standard knitting vocabulary, but here was a whole new language of craft shows and yarn brands and patterns. People knew the names of patterns, and bandied them about as familiarly as if they were best-selling novels or celebrities. “What are you working on?” “The Vostok shawl.” “Oh, of course! I’ve made a Vostok.”

“I went to a yarn shop in Australia,” one lady said, “and what were they selling? Koigu! Like, yes, I’ve heard of Koigu.” She rolled her eyes, and several people laughed.

Koigu, I learned after some surreptitious googling, is an indie Canadian yarn company, just over two hours away from Kitchener. Duh.

And here I was proud that I stopped buying all of my yarn at Michael’s in the last couple of years.

Despite how humbling the experience has been, however, it’s also been incredibly wonderful. Knitters are usually warm, kind, creative people, happy to answer questions and explain techniques. My first night, the circle’s sole male attendee - a flamboyant man knitting a rainbow shawl out of yarn from his own yarn company - graciously helped me undo a mistake in my sweater that had deterred me for the last three years. The circle’s members - ranging from an eight-year-old crocheter last night to women enjoying their retirement - have been uniformly friendly and sweet: shout outs to my four new friends who subscribed to Syllabus the same evening they met me!

And it has reminded me of one of the things I love most about Syllabus: every time I overturn a stone, there is a whole world hiding underneath.

Little Old Grannies

The cultural image of knitting is undeniably a feminine one, and has been for a very long time. The stereotypical knitter is a little old lady, sitting in a rocking chair by the fire with two long needles making a pair of socks.1

For at least the last two hundred years, knitting has been seen as cozy, domestic, and unthreatening: the perfect craft for grandmas and expectant mothers and good little Christian girls, to the point where it often serves as a shorthand for traditional femininity.

In The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), the Commander’s Wife Serena Joy - no longer allowed to read, write, or speak publicly - spends hours knitting elaborate scarves, ostensibly for soldiers on the front lines of Gilead’s wars:

She doesn’t bother with the cross-and-star pattern used by many of the other Wives, it’s not a challenge. Fir trees march along the ends of her scarves, or eagles, or stiff humanoid figures, boy and girl, boy and girl. They aren’t scarves for grown men but for children. Sometimes I think these scarves aren’t sent to the Angels at all, but unraveled and turned back into balls of yarn, to be knitted again in their turn. Maybe it’s just something to keep the Wives busy, to give them a sense of purpose. But I envy the Commander’s Wife her knitting. It’s good to have small goals that can be easily attained. (14)

In Gilead, knitting represents the ideal for Christian womanhood - and yet even there, captive Handmaids like Offred are not trusted with knitting needles, for fear that they might use them violently.

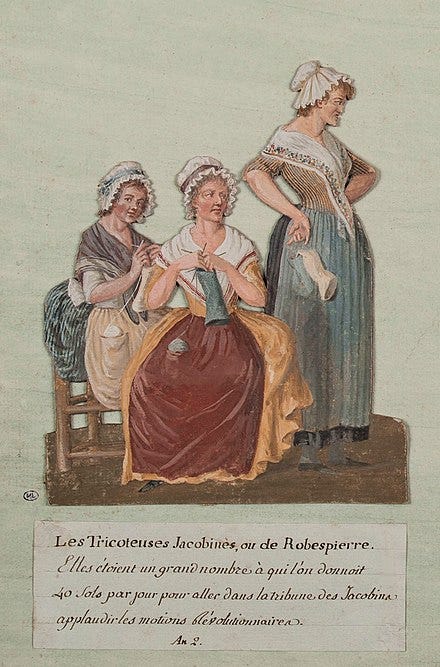

If knitting represents the ultimate feminine, then it also holds the potential for the monstrous feminine - an idea most famously seen in Madame Defarge, the creepy revolutionary in Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities (1859).

Madame Defarge sits every day in front of the guillotine, knitting away. She is a member of the historical tricoteuse, or “knitting women” - the working class women who marched on the Bastille, reported traitors, and knitted during trials and at the guillotine. For members of the French Revolution, these women were seen as heroic emblems of working class femininity, the “Mothers of the Nation.”

Dickens, however, portrays Defarge as a sinister figure, akin to the Fates of Greek mythology, her needles and yarn like their string. In contrast to the docile and faithful Lucie, Dickens portrays Defarge as sinister particularly because of the contrast between her feminine knitting and her third for bloody revenge.

Even in less dramatic contexts, knitting is often used as a shorthand to differentiate between tomboys and more traditionally feminine characters. In the first chapter of Little Women (1968-9), which is set in New England in the 1860s, we get this introduction to the free-spirited and gender non-conforming Jo March:2

“I hate to think I’ve got to grow up, and be Miss March, and wear long gowns, and look as prim as a China-aster! It’s bad enough to be a girl, anyway, when I like boys’ games and work and manners! I can’t get over my disappointment in not being a boy; and it’s worse than ever now, for I’m dying to go and fight with papa, and I can only stay at home and knit, like a poky old woman!” And Jo shook the blue army-sock till the needles rattled like castanets, and her ball bounded across the room. (5)

A few pages later, by contrast, we learn that the shy and much more traditionally feminine Beth “wiped away her tears with the blue army-sock, and began to knit with all her might, losing no time in doing the duty that lay nearest her, while she resolved in her quiet little soul to be all that father hoped to find her when the year brought round the happy coming home.” (12).

The association between knitting and traditional femininity has remained so persistent that second wave feminists often explicitly rejected knitting as a symbol of patriarchy and the domestic. As Beth Ann Pentney writes in “Feminism, Activism, and Knitting,” “second-wave feminists have been historicized as women who put down their knitting.”

By comparison, third-wave feminists, who have embraced knitting again as empowering, often frame the craft as a connection to their female ancestors. What remains consistent, however, is the idea that knitting is and always has been a craft for women.

The real story of knitting, however, is far more complicated.

Working Men

While other forms of making cloth and clothing out of spun fiber go back for thousands of years, knitting appears on the scene relatively late in the grand scheme of history: around 1000 A.D.

As the hosts of the podcast Stuff You Missed in History Class explain in their fantastic episode about the history of knitting, the craft was almost certainly developed earlier, but because knitting has historically been done using natural fibers, it is rare that intact artifacts survive.

The first knitted items we have are beautiful blue-and-white knitted cotton socks from Egypt, which archaeologists believe were knitted by fishermen using techniques that they evolved from their elaborately knotted nets. The sophistication of the design also suggests these were far from the first knitted items, if the average knitter today’s first uneven garter stitch scarf is anything to go off of!

Knitting spread throughout the Islamic world, eventually making its way to Europe, where it was primarily commissioned as decorative work for the very wealthy. Take, for example, this cushion cover found in a Spanish prince’s tomb, which dates from 1275 - the first known example of knitting found in Europe.

From there, knitting seems to have been taken up simultaneously by artisans and ordinary people. Women at home began knitting practical items of warm clothing for members of their families, establishing the craft as domestic and feminine enough that by the 1300s, art begins to appear depicting the Virgin Mary knitting!

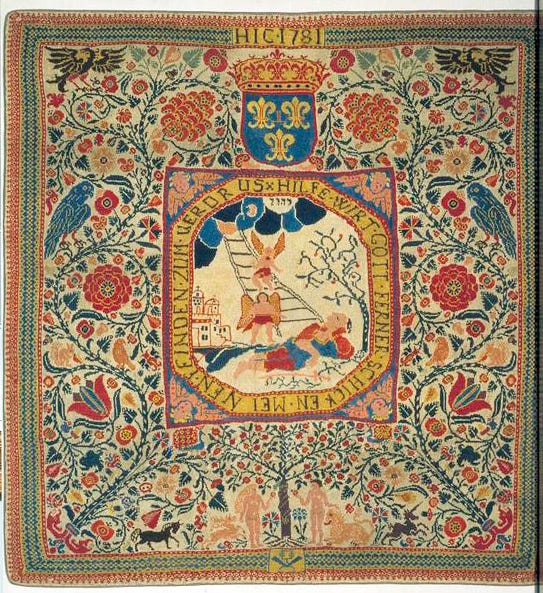

At the same time, however, formal knitting guilds appeared in France, and within the next few centuries they spread across Europe. In order to become a master knitter, a young man (and it was almost always a young man) had to study knitting for several years both at home and abroad, and then produce a number of fine master works, including an elaborate knitted carpet!

In 1589, a knitter named William Lee invented the knitting frame - the first knitting machine. When he applied to Queen Elizabeth I for a patent, however, she rejected his application: she was worried that the machine would hurt the existing knitting guilds. She was also purportedly a big fan of the recently developed knitted stockings, which were far more flexible and comfortable than historic woven ones - an early precursor, perhaps, to the “leggings as pants” trend!

Not to be deterred, however, William Lee and his brother moved to France, where they successfully popularized his machine. After William died, his brother returned to England in 1614, bringing his knitting frames with him. Now that Queen Elizabeth I was no longer on the throne, they faced less resistance, and in 1663 the Worshipful Company of Framework Knitters received a royal charter. In many ways, this charter spelled the beginning of the end for handknitting guilds; during the Industrial Revolution, knitting machines took up a larger and larger portion of the market for knitted fabric. While some women and children operated these machines, their heaviness meant that they were still frequently the provenance of men.

At the same time, however, hand knitting endured as a cottage industry, increasingly dominated (but not exclusively belonging to) women. While beautiful local traditions of knitting developed around the world, the British Isles are particularly famous for the numerous unique styles of knitting that developed there in the last few centuries.

Fair Isle, in the Shetland Islands, for example, created a beautiful multi-stranded style of patterned knitting that results in extremely thick, warm sweaters and other garments. In islands off the west coast of Ireland, meanwhile, craftspeople developed the famous Aran sweaters, elaborate sweaters knitted from undyed, water-resistant wool.3

This knitwear, while beautiful, was almost exclusively associated with working-class men and women: the homemade construction and thick wool fabric (a very practical fabric for cold, wet work) made it ideal as workwear.

That all changed, however, during a 1922 game of golf.

Sweater Weather

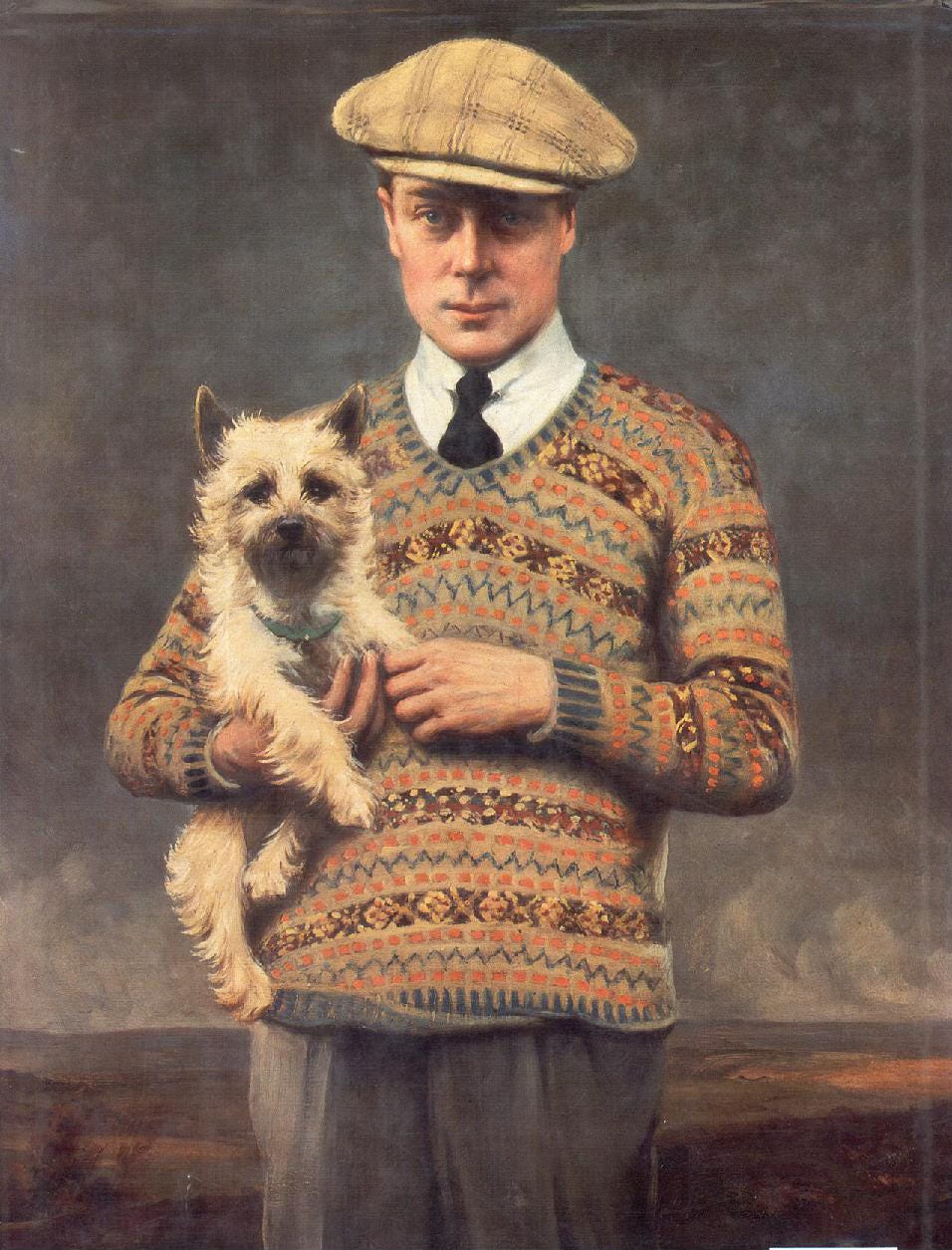

In the years following WWI, people were war-weary and desperate to enjoy life: fashion, music, sports, and party culture all saw dramatic booms in Great Britain. At the forefront of fashion was the future King Edward VIII, then the Prince of Wales. On September 27, 1922, the Prince of Wales played a game of golf in St. Andrews, Scotland, wearing the traditional wool trousers, jacket, tweed cap - and a shockingly colorful Fair Isle sweater gifted to him by Scottish artisans.

The sweater was an immediate sensation - considered almost vulgar, akin to George Clooney wearing a pair of Carhartt overalls to the Oscars!

Soon, the people of Fair Isle saw an unprecedented demand for their sweaters from the fashionable set, and the trend trickled down to the middle class as well; wealthier women started imitating historic working class knitting patterns as gifts for the men in their lives.

As the fantastic 2013 BBC documentary series Fabric of Britain explains in their episode about knitting, the Prince of Wales’s high-profile sweater moment set off a craze for knitwear in British fashion that would endure for the next sixty years.4

In the 1920s and 1930s, as sports and recreation became more popular, women knit their own stylish wool bathing suits. In the 1950s, as women settled into roles as wives and mothers, women’s magazines were filled with patterns for delicate, elaborate baby clothes as well as garments for adults. And, as the punk scene shook up the country in the 1970s, punks adapted knitting for their own style, creating sweaters and other garments full of intentional slashes, holes, and irregularities.

During WWII, however, knitting returned to the realm of survival. Fabric of Britain includes interviews with two elderly women who were teenage girls during the Blitz; they describe knitting in the dark, behind blackout curtains or in air raid shelters, as a way of passing the time and managing their anxiety.

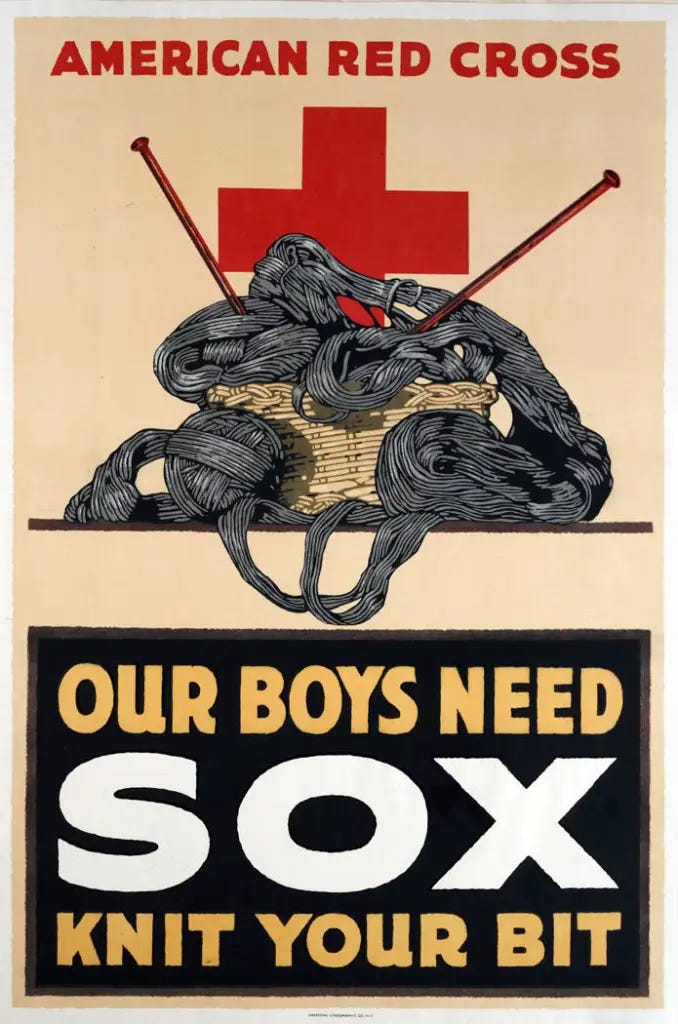

Knitting - particularly knitting socks, gloves, and other practical items for soldiers - was also seen as an important part of people’s civic duty during the war. Because Britain’s factories could not keep up with the troops’ demand for knitwear, civilians were issued government wool and patterns. Even the queen got involved, hosting a weekly knitting and sewing session at Buckingham Palace!

As this episode of the feminist podcast Stuff Mom Never Told You recounts, knitting was also a powerful spying tool during World War II; it was considered so perfect a method for information transfer, in fact, that during the war the British government banned the sending of knitting patterns to other countries through the mail, lest they contain coded information! In Belgium, meanwhile, elderly women working for the French resistance encoded reports about Nazi train schedules in their knitting to pass on to other agents.

The war also saw a resurgence in men knitting out of necessity: far from wives and mothers, men in the army and the navy were taught to repair their own socks and knit other simple items. The documentary includes a remarkable set of sweaters knit by British prisoners-of-war while they were held in German camps. One, knit by a former arts and crafts teacher, is beautifully constructed with several fine details; another is more clumsy, with one sleeve longer than the other, suggesting it was knit by an amateur who learned the craft in order to keep warm.

While researching this week’s Syllabus, I stumbled across a Reddit comment that reinforces the vital role that knitting played for POWs. As user KnittnchickP recounts:

My great uncle Lloyd was a POW in Germany during WW2. He learned to knit socks because he and the other POW with him were cold and wanted to keep their feet warm. Years after they were released they would exchange Christmas cards every year with the message “How’s your knittin’, kitten?”

Continue in Established Pattern

Today, knitting has seen a dramatic return to popularity: at the beginning of the twentieth century, feminists began vocally reclaiming the craft. This is best exemplified by Debbie Stoller, co-founder of the feminist magazine Bust, who wrote the famous Stitch’n Bitch: The Knitters Handbook (2003), ushering in a new era of hip, snarky, “not your grandma’s” rhetoric around knitting. “Yarn bombers” covered public objects with colorful knitted covers, both as a prank and as protest against public policy or warfare. At the 2017 Women’s March, millions of people donned bright pink knit or crocheted hats as a defiant reclaiming of Trumps “grab ‘em by the pussy” comments.

During the pandemic, as many people found themselves at home with a lot of anxiety and time - much as in WWII - they took up knitting again. Some estimate that demand for knitting materials increased by more than 200% worldwide, with high profile celebrities like Michelle Obama and Olympic diver Tom Daley getting in on the action.

And so we arrive at our current moment, and the world I unsuspectingly stepped into when I entered that knitting circle three weeks ago.

My local library carries a series of more than sixteen knitting-themed murder mysteries by Maggie Sefton, with delightfully punny names like Knit One, Kill Two; A Deadly Yarn; and Dyer Consequences.5 There are wildly successful knitting podcasts, such as Fruity Knitting, Pardon My Stash, and Grocery Girls Knit. One of my new friends at the knitting circle recently went on an entire knitting cruise!

Still, knitting remains persistently female-dominated: roughly 70% of American knitters are women. Despite the craft’s resurgence in popularity, it’s still frequently viewed as fussy and old-fashioned by outsiders, though that perception is slowly changing, due to the efforts of ordinary knitters and celebrities like Tom Daley alike.

It’s a real shame, too, because I have found knitting immensely soothing and helpful in dealing with my own anxiety. And I’m not alone in that - one of the hosts of Pardon My Stash talks about using knitting as a tool to manage her OCD. And - in a wonderfully contemporary example of literary knitting - author T. Kingfisher’s fantasy novel Paladin’s Grace features a paladin who knits socks on the go as a way of coping with his PTSD.

More than anything, attending the knitting circle this month has been a balm to my soul. It has been a reminder that even when the world feels cold and alienating, dominated by algorithms and AI and mass consumption, that we can still create genuine connections in our communities. All around us, with patience and care and craftsmanship, people are still making beautiful things, one hand-knit stitch at a time.

When it comes to knitting, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

As someone who has made socks, they are almost always knit in the round on a set of five double-pointed needles, which look far more perplexing than the two you almost always see in media.

In recent years, a theory has emerged that Jo March can be read as a trans man, and that Louisa May Alcott may also have been trans or gender nonconforming. You can read more about that theory here. I am currently rereading Little Women, and am struck by how many statements there are like the one above that Jo makes about her desire to be the man of the family, as well as her discomfort with and lack of interest in most feminine pursuits.

It’s often repeated that individual families would have their own patterns that they worked into the sweaters, ensuring that if a fisherman was lost at sea his body would be more easily identifiable. As far as I can tell, this is a myth that doesn’t show up until the beginning of the twentieth century.

I initially thought due to the length of that YouTube video that it was a three hour documentary about knitting, and was a little devastated to realize that this was not the case. The following episodes, however, are about wallpaper and embroidery, and I am genuinely excited to watch them soon - while knitting, of course.

I skimmed through Knit One, Kill Two, and unfortunately found the writing clunky and the murder uninteresting, if unintentionally funny due to the way that characters keep learning to knit and discussing yarn in the midst of threats to their lives and outbreaks of terrible violence in their small sleepy town. The one exception to the mediocre writing? The lush, almost pornographic descriptions of yarn and knitwear. Hey, Sefton knows her audience!

ALMOST persuaded me to try knitting again. 😁