Song of the Week: “The View Between Villages,” by Noah Kahan - “The things that I lost here, the people I knew / They got me surrounded for a mile or two”1

I went to Denver last week because ten years ago my friends Livvy and Ivan got married.

Their wedding took place at the end of the first semester of my senior year of university, a time when I was adrift in a sea of anticipatory nostalgia. I cried that year at the drop of a hat. My friends would make a midnight run to McDonalds, and I would start to weep: what if this is the last time that we randomly get McDonalds together at midnight?

The last three and a half years of my life had been the best ones yet. I had gone from feeling lonely and weird to feeling overwhelmingly seen and loved: by my professors, my classmates, and a large group of friends. I had taken road trips and traveled through Europe, been paid to write for the first time and made waves as the editor of the student newspaper. And now, I knew this era was coming to a close, whether I liked it or not.2

And so: Livvy and Ivan’s wedding, sparkling jewel-like at the apex of the year, only a couple of weeks before Christmas. I already had a front-row seat to their larger-than-life love story. I was there, the year before, when Livvy finished exams early so she could fly to Mexico and tell Ivan she wanted to be his girlfriend. I was there that May, in a crowd of cheering friends, when Ivan knelt in Livvy’s childhood treehouse and asked her to marry him and she said yes. And now I was there for the big finale.

Unlike most other couples on campus, Livvy and Ivan weren’t getting married in a church, but at the campus performing arts center. Their unconventional ceremony began with them standing separately on stage under two spotlights, using words, music, and projected images to tell the story of how they met in high school and fell in love: through prayer, through letters, through endless conversations.

And then, after they slipped away while video of that proposal played, they appeared decked out in suit and gown, arm in arm with their parents, walking up the two parallel aisles back to the stage, eyes never leaving each other. In that tiny, traditional town, it was one of the boldest and most cinematic things I had ever seen, and I was enthralled.

Except.

I was persistently, frustratingly single during those golden years in university. So single, in fact, that someone literally made a documentary about it.34

And so, in the midst of that perfect love story, I couldn’t help but wonder why that hadn’t happened to me yet. When, right before the vows, the officiant encouraged couples in the audience to reaffirm their promises to each other, my equally single friend Tim and I grabbed each other’s hands and muttered “We’re going to die alone!” And part of me really believed it.

Last week, in Denver, I sat on a plastic chair in an event space co-run by Livvy and Ivan. I watched them, sitting side by side illuminated by spotlights, retelling that same story they told ten years ago, word-for-word. I thought about all those golden days in that quiet little town: exploring flooded woods with Livvy and designing controversial issues of the student newspaper with Ivan, writing poetry and telling stories and going to shows together. But I also remembered the truth about how lonely I had been - and how I never could have known that, less than a year later, I would meet Taylor.

I never could have known that, seven years later, Livvy and Ivan would move to Colorado, and the four of us would make new memories, and Livvy would read a poem at our wedding, and we would laugh and sing and dance the night away.

I never could have known that, as I listened to Livvy and Ivan describe each other again ten years later after their wedding day, using the same wide-eyed imagery dreamed up by a couple of kids in love, my husband would be holding my hand.

In hindsight, my loneliness is less painful. In hindsight, it’s easy to buff the sharp edges off.

But I didn’t know any of that back then.

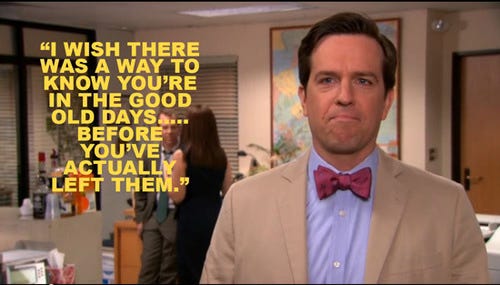

The Good Old Days

If you had to point to a moment in your life where you were the happiest, what would you choose?

As Taylor and I drove through Colorado last week, taking in the brilliance of the mountains cutting jagged lines through endless blue sky, and reminiscing about all the places and people there that we missed, the answer to that question seemed easy: September 2019.

Taylor had started a great new job, and we had moved into our first apartment all our own. We were talking about getting engaged soon (and indeed, Taylor proposed that Christmas!)

His friends Robert and Joey from high school had just moved to Colorado, and within an hour of meeting them for the first time I was already laughing so hard that soda threatened to come shooting out of my nose.

I was starting to get the hang of things in graduate school, and was teaching a wonderfully fun class about romance novels. And, best of all, we had just adopted a rambunctious, perfect little kitten named Minnie.

On my birthday, we spent an idyllic day in Fort Collins, CO, eating and drinking every delicious thing I wanted. I had Taylor snap a photo of me posing in front of a brick wall, feeling cool in my new shirtdress and asymmetrical haircut. “26,” I wrote in the Instagram caption. “Never felt more content about who I am, where my life is going, and who I’m living it with.”

Except.

That spring, I had started having regular panic attacks in the bathroom at work because of how anxious I was about graduate school, how much I felt like an imposter.5 One of my dear friends was in a relationship with an emotionally abusive man, and my grief over it kept me awake at night. Donald Trump was in the third year of his presidency, and every headline brought new fears that he would tax my scholarship, or deport international students, or start a nuclear war on Twitter. A global pandemic that would destroy jobs and relationships and trust and lives was on the horizon.

And also–so many essential things were still in the future. I hadn’t written a word of my dissertation. Livvy and Ivan hadn’t yet dreamed of moving to Colorado, and we were still two years away from that luminous October day of vows and dancing. So many people had yet to meet the loves of their lives. So many babies had yet to be born.

Golden Age

When I was in university, my friend Tim - the single one whose hand I grabbed at the wedding - was obsessed with F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925).

For those of you who somehow missed it in English class, The Great Gatsby is about a man named Jay Gatsby, who falls in love with a wealthy woman named Daisy when he is a poor soldier. Determined to become someone she could be with, he goes off to war and makes millions, then throws a series of impossibly lavish parties in hopes that the now-married Daisy will love him again.

The Great Gatsby is about a lot of things: the futility of the American dream, the hollowness of the Jazz Age’s glitz and glamor, the unjust privilege of the wealthy and beautiful.6 But it is also a novel about the deceptive allure of nostalgia.

Gatsby is convinced that, if he can only make things perfect, he can reverse time, undoing Daisy’s marriage and child, her rejection and his struggles. In a conversation with the novel’s narrator Nick shortly after Daisy comes to one of Gatsby’s parties, he makes this belief explicit:

“I wouldn’t ask too much of her,” I ventured. “You can’t repeat the past.”

“Can’t repeat the past?” He cried incredulously. “Why of course you can!”

He looked around him wildly, as if the past were lurking here in the shadow of his house, just out of reach of his hand.

“I’m going to fix everything just the way it was before,” he said, nodding determinedly. “She’ll see.”

He talked a lot about the past, and I gathered that he wanted to recover something, some idea of himself perhaps, that had gone into loving Daisy. (110)

In the film Midnight in Paris (2011), Hollywood screenwriter Gil Pender fixates on F. Scott Fitzgerald and his contemporaries.7 While on vacation in Paris with his awful fiancé and her parents, he can’t stop talking about how wonderful the city must have been in the past. “Imagine this town in the ‘20s,” he enthuses. “Paris in the ‘20s, in the rain. The artists and writers!”

Soon, Gil has a chance to live in the era he is so nostalgic for: a mysterious car repeatedly appears at midnight and transports him back to 1920s Paris, where he hobnobs with F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein and Salvador Dalí. In between dancing the Charleston and asking famous writers to read his manuscript, Gil meets a lovely young woman named Adriana. There’s only one problem: she is obsessed with the Belle Époque, the era of artistic flourishing in Paris that began in 1871.

When the two of them briefly visit the Belle Époque, however, the artists they meet dream about the Renaissance. Still, Gil struggles to convince Adriana that she wouldn’t be happier in the 1870s. “Adriana, if you stay here though, and this becomes your present then pretty soon you’ll start imagining another time was really your - you know, was really the golden time,” he protests. “Yeah, that’s what the present is. It’s a little unsatisfying because life’s a little unsatisfying.”

Gil and Adriana have both fallen victim to “Golden Age Thinking.” As Paul, a pedantic professor in the film whose words nonetheless ring true, explains: “Nostalgia is denial - denial of the painful present. The name for this denial is ‘Golden Age Thinking’: the erroneous notion that a different time period is better than the one one’s living in. It’s a flaw in the romantic imagination of those people who find it difficult to cope with the present.”

Great Again

I myself am often guilty of Golden Age Thinking. Taylor and I frequently speculate about how much easier our lives would be if we had been born twenty years earlier: entering adulthood during the relative peace and prosperity of the Bill Clinton presidency. I’d easily find a tenure-track academic job, he’d get in on the ground floor of the internet age, we’d be able to afford a house.

We forget about smoking in restaurants, Don’t Ask/Don’t Tell, the Gulf War, the AIDS crisis.

Or I daydream about how cool it must have been to live in the 1970s, to see Star Wars in theaters and wear bohemian outfits and listen to Fleetwood Mac’s Rumors for the first time. To be a part of second-wave feminism.

And I forget, of course, all the things that second-wave feminism was fighting for: workplace protections, nuclear disarmament, abortion rights, racial equality, the environment.

Golden Age Thinking becomes dangerous when nostalgia for a falsely idealized past is weaponized to control the present. Think of that most pervasive of contemporary political slogans: “Make America Great Again.”

Remember, it says seductively. Remember when America was great?

In research from 2021, psychologists Anna Maria C. Behler, Athena Cairo, Jeffrey D. Green, and Calvin Hall differentiate between individual nostalgia - which is positively correlated with social connectedness, meaning-making, and sense of self - and what they term “national nostalgia.” National nostalgia - the kind of nostalgia found in a slogan like “Make America Great Again” - appeals to an in-group’s anxieties about real and perceived threats from outsiders. As Behler et al. explain:

A content analysis of speeches by right-wing populist leaders in Western Europe found consistent themes of nostalgia for their country's “glorious past” while denigrating the country's present, as well as themes emphasizing that a) opponents of the party were the cause of this discontinuity between past and present, and b) increasing the country's strength and opposition to party opponents would return the nation to its former glory (Mols and Jetten, 2014).

Remember the past? these leaders whisper. Remember how everything turned out okay for you? Remember how safe you felt as a child? I can help you get back to that feeling. All you have to do is turn against your neighbors - these symbols of the unfamiliar and the destabilizing and the new. All you have to do is give me power. We can Make America Great Again.

When, we might ask, was this era of perfect greatness? Was it in the 1980s, when men were dying alone in hospitals and environmental regulations were being rolled back and income inequality skyrocketed? Was it in the 1950s, when schools and buses and lunch counters were segregated and married women couldn’t open a bank account or accuse their husbands of rape? Was it in the antebellum South, when the perfect façades of rolling fields and mansions like frosted cakes were built upon the bodies of human beings enslaved, tortured, and exploited?

There is, of course, no perfect time to be alive, no time in which the future is not terrifying in its uncertainty, in which the past does not beckon with the allure of “everything turned out alright” (even if that reassurance smooths over all the people for whom things did not turn out alright). We can not escape suffering, and thus we cannot escape nostalgia.

As the cultural critic Michael Grasso explains, regarding nostalgia’s origins:

Artist and scholar Svetlana Boym’s 2001 work The Future of Nostalgia examines this reactionary impulse toward looking back through the “pain” of nostalgia. Nostalgia was first defined as a disease of soldiers serving far from their native lands during the early modern period, Boym notes. It’s an expressly medicalized diagnosis of longing and pain, often triggered by music from a soldier’s homeland — from the Greek words nóstos, meaning “homecoming,” and álgos, meaning “pain.” There is a promise of “coming home,” but the realization that this past place and time can never truly be reached creates a painful cognitive dissonance.

We can never go home again.

Ten Years Later

I went to Denver last week because ten years ago my friends Livvy and Ivan got married. The day before their tenth anniversary, they recreated that wedding show for a crowd of family and friends, and I sat holding Taylor’s hand, slipping freely between the past and the present, feeling like it had been an eternity and no time at all.

But the next night they told a new story: a story about the ten years that followed.

This time, instead of wedding clothes, they wore identical outfits: denim coveralls and white sneakers. Equal partners in the work. But much felt the same as that first show, too. Again, they sat next to each other under two spotlights, and again, in dialogue they narrated their love story through words, music, and projected images.

In his discussion of Boym’s The Future of Nostalgia, Grasso notes that Boym offers two possible responses to nostalgia: “a ‘restorative’ version that seeks to recreate the nóstos of an idealized past, banishing the pain over progress and change, and a ‘reflective’ variety that revels in the álgos, in the imperfections and patina granted by time, that recognizes the flaws in our collective conception of the past and plays with those flaws.”

In the story that Livvy and Ivan told that night, they chose the reflective response. As they narrated their move from that small town in Michigan to Boston, and then to Denver, they spoke of wonderful moments of community and humor and joy: traditions founded and friendships made, goals accomplished and careers flourishing. But they were also incredibly vulnerable: about doubt and disappointment, deconstruction and depression. They spoke frankly and honestly about heartbreaks and faith, about moments when they experienced things differently.

As Ivan reflected near the end of the show, “If a wedding is agreeing to a future together, then writing an anniversary show is agreeing to a past.”

How easy it would have been to collapse those ten years into a story of inevitable triumph! How easy it would be to sand off the grief and frustration and loneliness and rewrite the story. But instead they sought to remember, and remember publicly, both the great times and the painful ones, and in that moment of public memory they gave us permission to share their vulnerability and honesty.

And then? And then we danced, and each step felt joyous and inevitable and new.

When it comes to nostalgia, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

It was unusually difficult for me to pick the song of the week this time - I could have just as easily gone with “All My Friends” by LCD Soundsystem, or “Rivers and Roads” by The Head and the Heart, or heck, even “Yesterday,” by the Beatles. When you really get down to it, it turns out roughly half of all popular songs are about nostalgia.

That is, assuming I passed my classes and got into graduate school. It’s very easy now, with a PhD, to forget the hours I spent crying on the ground, sure I wasn’t going to get in anywhere.

The documentary, which was pitched to me by an MFA student I worked with on the student association, was called Chasing Mr. Darcy, and it was supposed to be about me finding love. Needless to say, I did not catch Mr. Darcy, so instead the documentary ended with me getting into graduate school. Thank goodness there are no copies of this film floating around on the internet.

One might argue that the title Chasing Mr. Darcy rather misses the major themes and context of Pride and Prejudice. One might also argue that this smug, pedantic attitude might be part of why I was perpetually single in university.

Last week while visiting my friend Jenna from my PhD, she related a conversation with a fellow student where that student remarked that I had “come out of the womb” knowing how to do a PhD, and I was struck, as I am so often, by the vast and unfathomable gulf between how we see ourselves and how others see us.

It will never stop being funny to me how many rich people out there throw Great Gatsby-themed weddings and parties while completely missing the point of the novel. Yes, yes, I know, still smug and pedantic.

I really like Midnight in Paris, which is kind of like The Avengers for English majors, and I really, really hate Woody Allen, who is a predator. The question of how and whether we should separate art from the artist is one for a different Syllabus, but for now I would simply suggest that if you do watch Midnight in Paris, you try your best to ensure that Allen doesn’t make any money as a result.