Song of the Week: “Crowded Table,” by The Highwomen - “I want a house with a crowded table / and a place by the fire for everyone”

Anyone who knows me knows I love to cook and I love to eat. I love making meal plans and exploring new grocery stores, I love simmering bolognese over a whole Sunday afternoon or throwing together a stir fry after work, and most of all, I love feeding people.

Reading about food is a related, but entirely separate, hobby. Did I pick up Mimi Thorisson’s Old World Italian at the thrift store recently because I intend to “make the most sublime, yet elemental cacio e pepe”? Almost certainly not. But the glossy photographs of sun-drenched olive orchards and rustic wooden tables strewn with plump hand-shaped gnocchi, accompanied by equally sumptuous text, are their own indulgence.

Beyond cookbooks, of course, literature is full of wonderful food. My friend Jillian grew up on Brian Jacques’ Redwall series, books so bursting with lavish descriptions of food that for three years there was a Twitter bot that shared a different one every six hours. For example, from July 26, 2022: “Hazelnut and almond bread was served with pale gold cheese with chives and apples, a large honey and blackberry pie was brought out, and mountain pear cordial and melon juice flowed freely.”

The Risk of Hospitality

My favorite literary feast is poor Bilbo Baggins’s “Unexpected Party” which opens J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit. The titular hobbit’s unfailing politeness, commitment to hospitality, and well-stocked larder combine such that he ends up spontaneously hosting a dinner party for thirteen ravenous dwarves and one amused wizard. (Despite the uneven quality of the Hobbit movies overall, I love Peter Jackson’s depiction of this, which I have included below.)

After Bilbo has already offered up tea, and beer, and cake, the dwarves start making specific requests:

“A little red wine, I think, for me,” [Gandalf said].

“And for me,” said Thorin.

“And raspberry jam and apple-tart,” said Bifur.

“And mince-pies and cheese,” said Bofur.

“And pork-pie and salad,” said Bombur.

“And more cakes - and ale - and coffee, if you don’t mind,” called the other dwarves through the door.

“Put on a few eggs, there’s a good fellow!” Gandalf called after him, as the hobbit stumped off to the pantries. “And just bring out the cold chicken and pickles!”

“Seems to know as much about the inside of my larder as I do myself!” thought Mr. Baggins, who was feeling positively flummoxed, and was beginning to wonder whether a most wretched adventure had not come right into his house. (11-12)

Mr. Baggins, of course, is right: an adventure has come to his house, and the meeting that begins at his table will eventually send him out the door and down the road on a journey that will test his courage and broaden his horizons.1

This is the risk of opening our doors and welcoming others to our tables: that people might eat too much, or break our prized plates, or make us uncomfortable. It can be tempting to keep our meals to a regular and orderly few: to retreat inside of gated communities instead of feeding the hungry in shared spaces, like my friend Dakota did every Sunday for years with Food Not Bombs. To have a crowded table, we must believe that there will be enough for everyone. We must believe in abundance.

Loving, Cooking, Cooking, Loving

One of the most compelling - and troubling - depictions of this kind of open-hearted abundance occurs in Beloved (1987), Toni Morrison’s searing novel of slavery and its aftereffects. Beloved is chilling, heartbreaking, beautiful, and repulsive in turns, and far too complex a text for me to provide much meaningful analysis here. The novel centers on an act of unthinkable violence. This act is done in desperation and is the end result of a chain of events enabled, in part, by resentment: resentment of an elderly, formerly enslaved woman named Baby Suggs who ministers to her neighbors both with food and with her words.

Too much, they thought. Where does she get it all, Baby Suggs, holy? Why is she and hers always the center of things? How come she always knows exactly what to do and when? Giving advice; passing messages; healing the sick, hiding fugitives, loving, cooking, cooking, loving, preaching, singing, dancing and loving everybody like it was her job and hers alone.

Now to take two buckets of blackberries and make ten, maybe twelve, pies; to have turkey enough for the whole town pretty near, new peas in September, fresh cream but no cow, ice and sugar, batter bread, bread pudding, raised bread, shortbread - it made them mad. Loaves and fishes were His powers (161).

I don’t want to dwell today on the resentment, however, but on Baby Suggs’s generosity, and on Morrison’s tiny mirrored phrase: “loving, cooking, cooking, loving” (161).

“Why?” Baby Suggs’s neighbors ask. Because, as we learn throughout the novel, Baby Suggs sees herself as a lay pastor called to minister to her people, whose minds and bodies are shattered from living under the weight of chattel slavery. In a clearing in the woods - her church - she gives her people their bodies, and commands them to love their flesh: their hands and feet, their mouths and their hearts (101-103). In affirming her neighbors’ bodies, Baby Suggs affirms their dignity and their personhood; in nourishing them she loves them into being.

Fed by God

The holiness of shared meals appears in many religions throughout the world: sharing food with others, both believers and outsiders, is sacred.

A central tenet of Sikhism is the langar, an enormous communal kitchen where simple vegetarian or vegan meals are served every day to anyone who wants one. The largest langar in the world, the Golden Temple in Amritsar, India, serves as many as 100,000 free meals a day.

The heart of Judaism, Shabbat, opens with a shared meal on Friday evening. In the podcast On Being, Krista Tippet shares the story of a teenage white supremacist who renounced his racist beliefs because of the friendships he formed when, while in university, an Orthodox Jewish student invited him to Shabbat dinner week after week.

And in Christianity, the tradition I come from, there is the Eucharist, or communion: breaking bread and drinking wine together to commemorate the sacrifice made by Christ. I love the understanding of communion found in Sara Miles’s memoir Take This Bread (2007). Miles was an atheist who wandered into a San Francisco church, took communion, and then felt called: to transform the church every Friday into an enormous food pantry feeding the city’s homeless and hungry.

“Because of how I’ve been welcomed and fed in the Eucharist,” she writes, “I [saw] starting a food pantry at church not as an act of ‘outreach’ but one of gratitude. To feed others means acknowledging our own hunger and at the same time acknowledging the amazing abundance we’re fed with by God” (116).

Stay for Potluck

When I was in university, most of us did not have our own homes or even our own tables, nor could we afford to feed ten or fifteen people at a time. But we could each usually afford something: napkins, or two bags of chips, or a loaf of bread, or a block of cheese. So we would have potlucks.

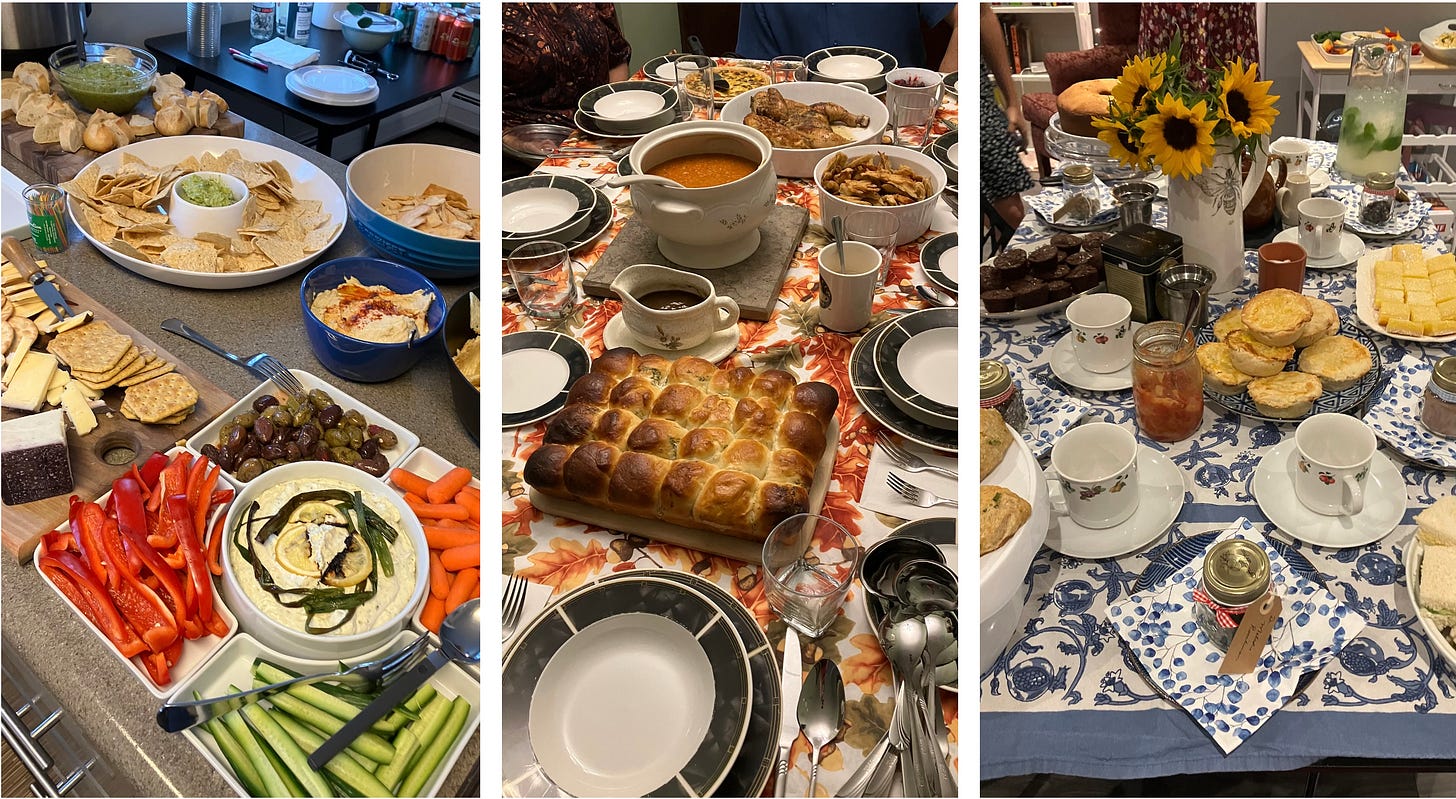

For two years, my friends Cassie and Satoshi organized a potluck in the lobby of one of the dorms every Saturday, and invited anyone who wanted to to join them. We spent hours there, eating haystacks off of paper plates and debating politics, or munching on sandwiches and reading quietly as snow fell outside.

One of my favorite memories from those years was on a magical Saturday night one April, when so much rain had fallen that the woods flooded and we paddled through them in an inflatable boat my friend kept in her trunk.

Back on dry land after this adventure, we had a potluck. I had brought my culinary pride and joy at the time, which I made using hand-me-down tools in my dorm’s dingy kitchen: vegan potato salad. In our high spirits that evening, one of us accidentally knocked the bowl and all of its untouched contents onto the ground. The potato salad was so good — and we were so hungry — that we knelt in the dirt, shoulder to shoulder, with forks outstretched, and carefully ate all of the salad that wasn’t touching the ground anyway.

Here is the recipe for that salad:

Melodie’s Vegan Potato Salad

(Makes a generous portion as a side, at a potluck - scale as you see fit)

Several yellow or red potatoes, skins on, diced then boiled in very salty water for 15 minutes

1-3 cloves of raw garlic, minced

1 bunch green onions, sliced

1 bunch fresh dill, chopped

1 cup or so dill pickles, chopped

2-3 large lemons, zested and juiced

Good olive oil, drizzled till it coats the potatoes evenly

1-2 tbsp Dijon mustard

Kosher salt and fresh ground black pepper

Combine all ingredients while potatoes are still warm, seasoning to taste. If possible, allow potato salad to soak up dressing for at least one hour before serving. Serve room temperature or cold. Dirt is optional; company is highly encouraged.

When it comes to crowded tables, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

Bilbo, for what it is worth, learns a great lesson in hospitality from his adventures in The Hobbit. In The Fellowship of the Ring, sixty years later, Bilbo throws a lavish “long-expected party” for his 111th birthday, and feeds nearly every person in his community continuously for more than seven hours straight.