Song of the week: Thrift Shop, by Macklemore - “I’ll wear your granddad’s clothes / I look incredible”

I was thrifting before it was cool.

When I was a kid, one of my favorite ways to spend a Sunday afternoon was at Value Village with my mom. We’d spend hours piling our separate carts high with anything that looked interesting, then grab adjoining change rooms and help each other judge our favorites. Afterwards, a full garbage bag or two worth of new finds in the back seat, we’d go to Pizza Pizza and split a slice and a salad. Then, of course, when we got home, we’d give my captive father a fashion show, emphasizing with each item what a good deal it was.

When I was in elementary school, even though I loved the thrifting trips themselves, I was embarrassed to admit to anyone that I shopped at Value Village. Abercrombie and Hollister reigned supreme, and wearing used clothes would be akin to admitting to embarrassing poverty. So my favorite things to thrift were t-shirts and hoodies with prominent brand logos: if my classmates saw me wear those, I reasoned, they’d assume I bought them at the mall, and I’d be Cool.1

In high school and university, of course, the goal posts shifted. Now I wanted to stand out, and again, thrift stores were there for me, providing a cheap assortment of questionable sartorial choices: fringed and studded jeans, a beaded lime green kurta, t-shirts from bands I had never heard of.2

In university, we’d go to the tiny local thrift store and search for the racks for treasures: brightly-hued stilettos, old dresses, an oversized men’s sweater that I wore with leggings and a beanie to chilly morning classes. It was the age of the hipster, and thrifting gave us the opportunity to wear something nobody else had.

And now, as an adult, disillusioned by overconsumption and frustrated by the shoddy quality of most goods I can afford new, thrift stores are still there for me. When Taylor was unemployed and money was tight, I thrifted books and antiques to give as Christmas gifts. I wear cashmere sweaters, linen trousers, and Italian leather shoes, all purchased for pennies on the dollar. One of my prized possessions is a fine wool blazer from a company that dresses the British Royal family. It retails for upwards of $1000 CAD. I got it for $14.99.

Buried Treasure

My brother, Paul, is an archaeologist, and his best and most exciting work happens when he finds someone’s trash heap.

In the garbage dumps of history, archaeologists can learn about what a society wore, ate, worked on, and played with, all at an artifact density that’s hard to find elsewhere. Whenever I thrift, I feel like I am doing a much easier version of that archaeological work, sifting through the things people thought were valuable enough to save from the garbage can, but not valuable enough to keep for themselves.

Visit any thrift store in North America and you’ll see the usual suspects: fad diet cookbooks and fundraiser t-shirts, beat-up sneakers and tacky souvenirs. But you’ll also find archives of entire lives lived: books with heartfelt inscriptions given at Christmas, wedding china with finely painted roses, collections of carefully hand-knit sweaters. And then, of course, there are the strange and funny finds, that you prize not for their market value but for their uniqueness - such as this bird-shaped basket that holds my plush Gollum like he’s baby Moses in the Nile.3

In the right mood, a thrift store feels like a mysterious shop from a fantasy novel, potentially containing a magical object that will change your life. Consider the thrift store at the beginning of Ann Brashares’s YA classic The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants: the teenage Carmen buys a pair of jeans for $3.50, then discovers that they fit not only her but her three very different friends perfectly.

The pants are the only supernatural element of the Sisterhood series, connecting the four girls as they travel, attend university, fall in love, and experience heartbreak. “Magic comes in many forms,” Carmen declares. “Tonight it comes to us in a pair of pants.”

Of course, magical pants aside, there is still the dream of finding a precious piece of jewelry or priceless artifact among the discarded Forever 21 tank tops and World’s Best Boss mugs. That’s the gimmick behind HGTV’s short-lived Endless Yard Sale: Showdown, a reality show in which teams spend $1000 on used goods over two days, then have their finds professionally appraised. Whichever team’s finds are deemed the most valuable wins. Their reward? They get to keep the assorted furniture, farm implements, and pop culture memorabilia they’ve been hauling around in their trunk for the last forty-eight hours.

I watched the lone episode of Endless Yard Sale: Showdown available on YouTube, and was disappointed to discover that it didn’t feature any yard sales at all. Despite the fact that every stop on the competitors’ route is part of the World’s Largest Yard Sale (a shopping corridor that stretches from Michigan to Alabama), there wasn’t a yard sale in sight. Instead, competitors exclusively visited flea markets and estate sales, frequently dropping hundreds of dollars on designer furniture that the sellers already knew was valuable.

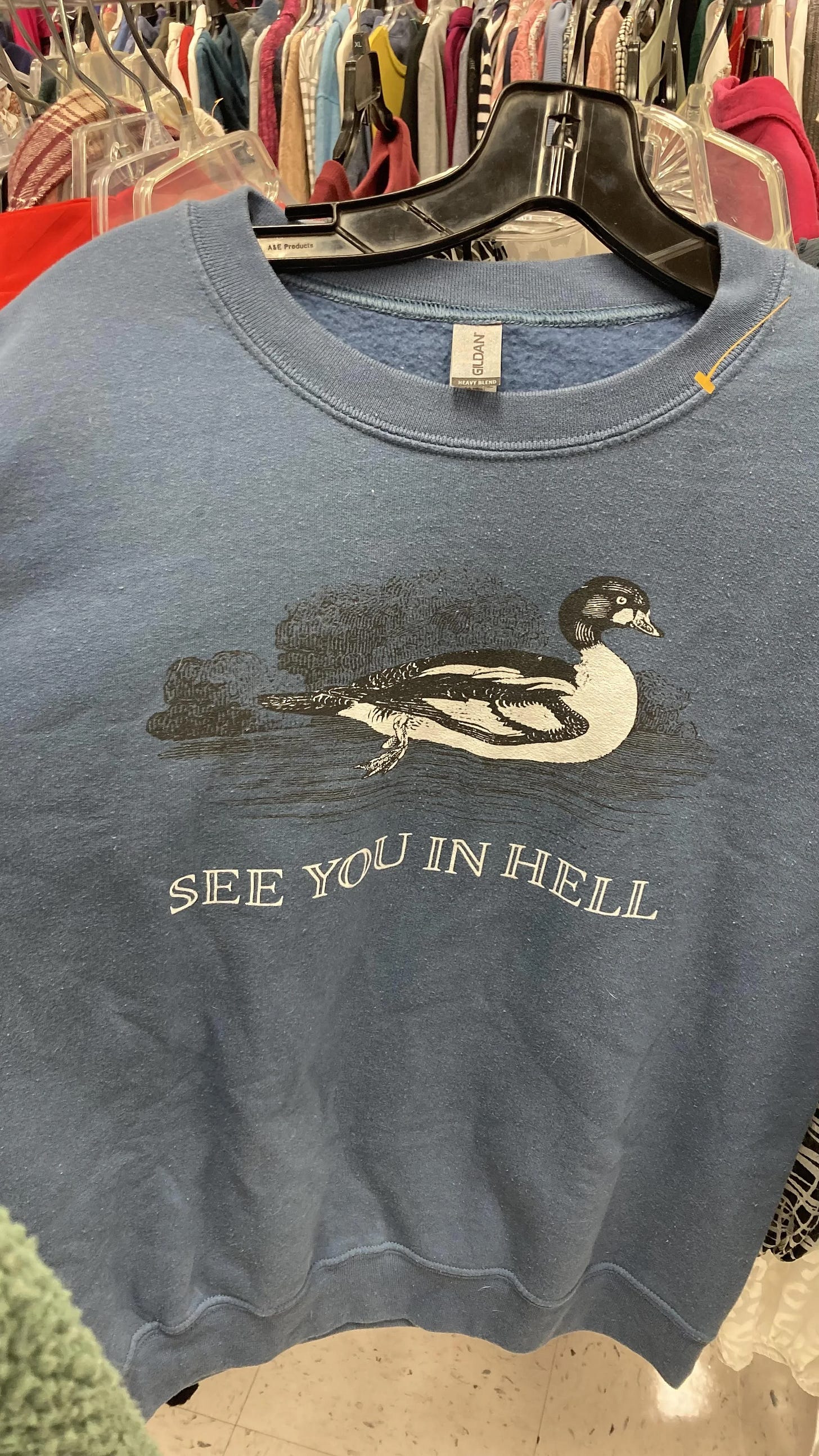

One of my guilty-pleasure subreddits, r/thriftstorehauls, is much more satisfying. Ordinary people post pictures of the incredible things they found for cheap at thrift stores, yard sales, estate sales, and through websites like Facebook Marketplace. The top posts of all time include genuine diamond earrings purchased for $6.99, mid-century modern furniture, a set of high-end Le Creuset dutch ovens - and this sweatshirt.

One man’s trash, etc.

When it comes to thrifting something valuable, however, Anna Lee Dozier must take the cake.

A few years ago, Dozier was thrifting at a shop near a Washington D.C. Air Force base when she found a faded pottery vase for $3.99. It reminded her of the vases she had seen in Mexico while traveling as part of her work with Christian Solidarity Worldwide, so she bought it, put it on a shelf in her home office, and thought nothing of it.

Last year, however, while visiting the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, she saw several vases that looked suspiciously similar to hers. When she got back home, she sent some photos to the Mexican Embassy, and was shocked by their reply: the vase she had thrifted was a priceless Mayan artifact dating from 200-800 AD.

The Mexican officials politely asked for the vase back, and Dozier agreed, returning it in a small cultural ceremony at the embassy. The return was only one of more than 13,500 lost or stolen artifacts that the Mexican government has repatriated in the last few years.

While many online commentators complained that she could have made a fortune from the sale of her find, Dozier never considered selling the vase once she realized its origins. “It has value beyond what you could put money on,” she told CBC’s Sheena Goodyear. “And so for me, it just was never a question. If it was something special, it should go back to where it belongs. I feel very lucky that I got to find it and have it in my house for a few years, but now it’s going back where it should be.”

Your Grandad’s Clothes

Thrift stores are a relatively modern invention. For most of human history, the average person owned very few items, and the items they did own were used and reused for as long as possible. Furniture was custom built, clothes were resized and shared as hand-me-downs, and “My Dad Went All the Way to Key West and All I Got Was This Lousy T-shirt” shirts were far less abundant.4

The first thrift stores were pop-up fundraising shops held by organizations like the Red Cross at the turn of the 20th century. Charity shops as we know them, however, caught on during World War II, as citizens combined their resolve to “make do and mend” with their desire to help the war effort. Stores like those hosted by the Red Cross helped poor and marginalized people access necessary goods, and their proceeds went to help those impacted by the war.

Today, many thrift stores are still set up to raise money for both religious and secular non-profits, so much so that in the UK thrift stores are called “charity shops.” In the United States and Canada, in addition to non-profit giants Goodwill and the Salvation Army, you can often find individual mission-oriented thrift stores, such as one I visited last weekend here in Kitchener that helps survivors of domestic violence. There are also chains of for-profit thrift stores like Value Village, Savers, and Talize that make donations to nonprofits based on the donated items they receive, but sell those donations for profit.

The 1950s saw a shift towards conspicuous consumer culture, particularly in the United States, as the booming post-war economy and push for domesticity encouraged Americans to buy, buy, buy. As people were encouraged to “refresh” their wardrobes and home decor, they became more likely to donate their unwanted goods or sell them for cheap at yard sales.

Ironically, though those 1950s shoppers were consuming at a rate never seen before in American history, the goods they purchased now seem unusually high quality, the size of their homes and wardrobes quaint.

While it was surprisingly difficult to find concrete numbers on the size of the average woman’s wardrobe in the 1950s, we know for a fact that they owned far less clothing than women do today. This website, for example, suggests that a middle-class woman in a cold climate would own four coats and jackets, a suit, ten dresses, three skirts, three blouses, and three sweaters, along with some more casual clothing: more than her grandmother, certainly, but a capsule wardrobe compared to modern consumption!

By comparison, in 2024 I took an inventory of my closet: I owned 10 coats and jackets, 7 suits and blazers, 14 dresses, 21 pairs of work-appropriate pants, 10 skirts, 20 shirts I could wear to work, and 23 sweaters, not to mention an enormous collection of shorts, t-shirts, pajamas, and accessories. Now, granted, I love clothes, and the majority of those clothes are thrifted or homemade, but still. My full-to-bursting closet is a symptom of a larger societal problem.

Trash

When I’m in a bad mood, I walk into a thrift store and see what so many other people see: a building filled to the brim with grubby, broken-down, unwanted garbage. A truly staggering amount of garbage.

Not for nothing did the rapper Macklemore, in his 2013 appearance on Sesame Street, parody his hit single “Thrift Shop” with the help of Oscar the Grouch, declaring “I’m shopping / looking for some rubbish.”

Thrift stores as we know them only exist because we produce and buy far more goods than we need - and then when we get tired of them, we get rid of them.

Today, clothes are the cheapest relative to income that they have ever been - and the world’s clothing consumption is out of control. Fast fashion production has doubled since 2000.

Every year, the fashion industry produces 100 billion garments, and 92 million tons of textile waste. This is disastrous for the planet: 10% of all global emissions are from the fashion industry. It takes 2,700 litres of water to make one t-shirt: the equivalent of one person’s drinking water for three years.

While access to cheap goods means that people around the world are wearing more than ever, wealthy countries are the worst offenders. The average American throws away 81.5 lbs of clothes a year, and only wears individual items of clothing an average of 7-10 times before they’re thrown away. Globally, the number of clothes being thrown away is equivalent to a garbage truck full of clothes being put in a landfill every second.

And, as is so often the case, those consuming all these clothes are not the ones paying the true price. As Giorgio Kaldor reports in a 2022 article, used clothes are shipped to Africa in 50 kg bales. In Ghana, there is an idiom that describes these shipments - obroni wa wu, or “the clothes of the dead white man.” “They are so many,” Kaldor writes, “[that] they breed, in those who receive them, the idea that only those who are dead could turn their back on such material abundance.”

To make matters worse, only 10% of the clothes shipped overseas are good enough quality to be reworn or upcycled. The rest end up in landfills, with heaps of clothing over 60 feet high.

While the fashion industry as a whole is responsible for this horrific waste, one player stands out: SHEIN. Founded in China in 2008, by 2022 SHEIN was the world’s largest and most successful fashion company. SHEIN produces a truly staggering amount of clothing: more than 1 million new garments every day. These garments, which retail for rock bottom prices, are unethical in every way: with designs often stolen from artists and small designers, cheap polyester fabric, and shoddy construction, they are meant to be worn only once or twice and then thrown away. In order to produce such cheap garments at such an absurdly fast pace, workers in SHEIN’s factories work as much as 75 hours a week. SHEIN has also been accused of using child labor and slave labor: accusations they have not been able to disprove.

As Ava Gilchrist and Amy Bradney-George write for Elle, “The company is not just bad or cheap, but a deplorable example of the dangers of the micro-trend cycle and exponential speed in which fast fashion is accelerating the industry.”

But let’s say you don’t care about the waste generated by the industry, or the working conditions that enable SHEIN’s prices. After all, companies with much higher prices such as Nike have been criticized in the past for their labor practices.

You still shouldn’t buy SHEIN clothes - because they could give you lead poisoning.

In a 2021 CBC Marketplace investigation of SHEIN clothes, they found that 20% of clothes sampled contained elevated levels of chemicals, including lead, PFAS, and phthalates, that could be extremely hazardous to one’s health. Most shockingly, a toddler-sized jacket contained twenty times the amount of lead that Health Canada says is safe for children.

“This is hazardous waste,” says Miriam Diamond, an environmental chemist and professor at the University of Toronto. “If the final product isn’t safe for me, it’s definitely not safe for the workers that are handling these chemicals to make it.”

Fast fashion is negatively affecting thrift stores, too. Because influencers often buy dozens of SHEIN clothes at a time to make “haul” videos or take photos of, then immediately donate them, thrift stores are increasingly full of SHEIN clothes. As Ann Helen Peterson points out in an episode of her Culture Study podcast, “How Did Thrifting Get So Bad?”, it’s getting more and more difficult to find good quality clothing in thrift stores as they’re flooded with low-quality fast fashion. Add in the prevalence of professional resellers who scour thrift stores and other similar marketplaces for items by the dozen that they then upsell for much higher prices, and the ratio of trash to treasure in thrift stores is higher than ever.

While the old-fashioned kind of thrifting is getting more expensive and more difficult, however, it is easier than ever to buy clothes (and other goods) used. Facebook Marketplace, eBay, and clothing-specific websites like Poshmark and Depop make it easy shop for pre-owned clothes without having to spend hours sorting through the racks at your local Goodwill.5 Furthermore, companies like Patagonia and Levi’s are buying their used items back from customers and selling them directly on dedicated websites. And, if you’re willing to pay more for someone else to do the curation work for you, both high-end and midrange consignment shops like Plato’s Closet and Buffalo Exchange sell clothes that are guaranteed to be stylish and in good condition.

Currently, used clothes account for 3.2% of the global fashion industry. Experts estimate that market share could climb to 23% by the end of the decade, resulting in an annual carbon emissions reduction of 340 million tons: more than the annual emissions of France or Thailand.

The Thrill of the Hunt

But beyond all of it - beyond the environmental and human rights concerns, the cost savings, the search for quality - I thrift as much as I do because it is fun. The low barrier to entry, the thrill of the hunt, the wild and kooky things you find along the way: all of them transform thrifting from a task into a hobby. Whenever I walk into a thrift store, I hope that I will find the perfect broken-in LL Bean flannel, or a 1940 copy of Pride and Prejudice (both things I have thrifted). But I know, beyond a shadow of doubt, that I will find something ridiculous.

Last night, I went through my camera roll and found more than 70 photos just from the last two years of absurd items I laughed enough at to photograph and send to my friends, like this painting of a creepy minstrel child:

Or this pair of…fish…shoes?

Or this vintage cookbook, with a photo of an awkwardly-toasting woman that has become an inside joke for Taylor and I.

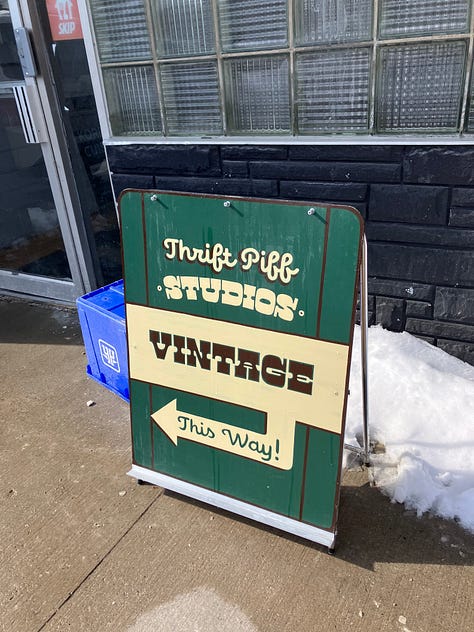

Even if I walk out of a thrift store empty-handed, I have a great time. The pull of the thrift store is so strong, in fact, that last weekend I followed a series of mysterious signs to the back of a building, where I discovered - to my relief - an incense-scented pop-up shop selling vintage skateboarding apparel. “If someone ever wants to steal my organs,” I joked with the cashier, “all they have to do is tell me they’re running a thrift store.”

I decided to write about thrifting this week because I visited three new thrift stores last weekend alone, and because I needed an emotional break from the heaviness of what I’ve been thinking and writing about constantly these days.

But I realized last night that this topic also feels relevant because this week - incredibly - marks one year of Syllabus.

One year of late nights and stacks of library books, offbeat connections and eleventh-hour subject changes. While some essays have easily come together, driven by an unusual clarity of purpose, many other weeks I’ve set out with nothing but a sense of vague curiosity. I’ve discovered fascinating and quirky things throughout my journey: Colonial cookbooks and bad citations on Wikipedia, dandelion fan sites and competitive Scrabble documentaries. Each week I’ve gone digging, never knowing quite what treasure I’d uncover.

This week, for example, I discovered a 2001 documentary, Atomic Ed and the Black Hole, about a nuclear weapon-manufacturer turned anti-war activist who runs a thrift store in the New Mexico desert selling salvage from the Los Alamos nuclear research facilities to history buffs, computer nerds, and artists. The YouTube copy of the documentary is a recording of a VHS being played on an old TV, and it only has 1,616 views.

I couldn’t figure out where to fit that documentary in this week’s Syllabus, but I’m so glad I got to spend half an hour with Ed.

These days, I feel disillusioned about so many things: politics, capitalism, the internet, the future. But once a week, Syllabus has given me the impetus to slow down, engage deeply, and articulate what I find to be good and beautiful and true. I’m so grateful for that.

Thank you for continuing to come with me as, week after week, I sort through the trash and share the treasures I find with you.

When it comes to thrifting, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

I wasn’t entirely wrong. In eighth grade I needed to buy a winter coat, and begged to be allowed to splurge on a cropped bomber jacket with a furry hood at Garage, an edgy mall store, instead of my usual Zellers coat. I got the coveted coat, and when a friend complimented it at school a couple of weeks later, I beamed and said “Thanks, it’s from Garage.” This was such an achievement that an adjacent Popular Kid, Russell, did a double take, looked at me with newfound admiration, and said ‘Wow, you’ve changed.’”

A year into university, someone saw my t-shirt, stopped me and said ‘I love “Murder By Death!” I hadn’t even realized it was a band - I just thought it was a cool phrase to put on a t-shirt. Oops.

Gollum was not thrifted, but rather bought new as part of a limited-edition Build-A-Bear release a few years ago. He is my terrible adorable son, and when we showed my friend Elisabetta the Lord of the Rings movies for the first time last year, she insisted he sit with her.

Though, incredibly, cheaply made souvenirs pre-date our contemporary age. In 2019, archaeologists found an iron stylus in London bearing the inscription: “I have come from the City. / I bring you a welcome gift /with a sharp point that you may remember me. / I ask, if fortune allowed, that I might be able (to give) / as generously as the way is long (and) as my purse is empty.” In other words: “Someone went all the way to Rome and all they got me was this lousy pen.”

This is especially important for plus-sized shoppers, who often have very limited options at local thrift stores.

Congrats on 1 year! So glad to have been able to join you on this ride! And on many thrifting adventures.

Congratulations on your one-year Syllabus anniversary! I’ve learned so much along with you and enjoyed every one.