ON: Corsets

Rifling through the underwear drawers of history

Song of the Week: “No Air,” by Jordin Sparks - “Tell me how I’m supposed to breathe with no air”1

Note: we’re talking about underwear this week. There’s nothing pornographic here, but some of the clips and images included might not be the safest for work.

I recently rewatched Bridgerton and remembered how much the show’s costumes - which can charitably be called “fantasy Regency” - simultaneously delight and irritate me. Though Bridgerton became famous for its empire-waisted gowns, fanciful floral prints, and swoony men in cravats, linen shirts, and brocade vests, it opens with a corset.

Prudence Featherington grips a maid’s hand while another laces her into a long-torsoed undergarment that - to my horror - she is wearing over her bare skin.

Later, we see the protagonist Daphne Bridgerton wearing a much shorter undergarment resembling a modern bralette. Again, horribly, she wears it without anything underneath: a condition that results in her skin becoming red and chafed.

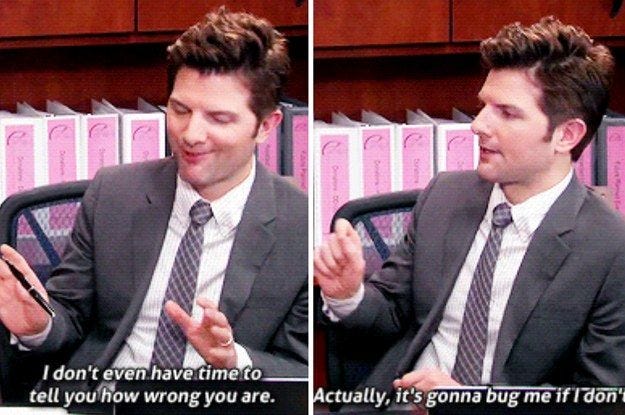

I haven’t been able to stop thinking about how much Bridgerton’s weird corsets annoyed me, and this week’s newsletter is the result of my ensuing deep dive into the history of the corset. Ben Wyatt and I have that trait in common:

First and foremost: I am no dress historian, but it is safe to say that ordinary women - in the four hundred years or so that they regularly wore corsets - never wore them directly against their skin.

Corsets were designed to be worn over a thin cotton or linen shift or chemise, not against bare skin like a modern bra. You can see a much more historically accurate version of this combo in this deleted scene from the 2020 adaptation of Jane Austen’s Emma.

Also, for the record, corsets wouldn’t have been called “corsets” during the Regency period (c. 1795-1837), or the three centuries before it during which women wore structured, waist-defining undergarments. Rather, these garments were called “stays.” The word corset - derived from the Old French cors, or “body” - only became popular in English near the end of the Regency period; while the Oxford English Dictionary records occasional uses in the preceding centuries, its first mention of a “corset-maker” is from 1837, suggesting widespread adoption of the term. I’ll continue using the term “corset” throughout this week’s newsletter, though, specifically because of its contemporary familiarity.

These first two depictions of corsets can tell us a lot about Bridgerton’s priorities - the ways in which it simultaneously frowns at patriarchy while also finding its structures and constraints intriguing, even sexy. Even as Bridgerton delights in the aesthetics of history, it is not particularly interested in what life was actually like. Its depiction of society has as much in common with historical realities as its #regencycore lingerie has with the actual historical garments.

Caging the Body

Is there any more iconic symbol of women’s historical suffering than the corset? Whenever filmmakers want to emphasize the ways that society constrains women, or expects them to conform to unrealistic beauty standards, or forces them into an arranged marriage, you can guarantee that we’ll get a scene of a servant or mother yanking on corset strings until our protagonist can barely breathe.

In Titanic, for example, which I also rewatched last month, Rose’s mother Ruth laces her daughter into her Edwardian steel-boned corset even as she reminds her of the role they both must play as upper-class women:

“Of course it’s unfair,” Ruth concludes. “We’re women. Our choices are never easy.” Then she kisses her daughter, and keeps tightening the laces.

While James Cameron is never subtle, he also famously has a punishing commitment to historical accuracy that Bridgerton doesn’t dream of. Rose’s exquisite costumes in Titanic are extremely faithful to her time period - as is the scene’s treatment of her corset as a symbol of oppression. For decades before the Titanic set sail, feminists were calling for an end to the garment.

In 1873, for example, suffragette and dress reformer Elizabeth Stuart Phelps Ward wrote in her pamphlet What to Wear:

So burn up the corsets! No, nor do you save the whalebones. You will never need whalebones again. Make a bonfire of the cruel steel that has lorded it over the contents of the abdomen and thorax so many thoughtless years, and heave a sigh of relief; for your ‘emancipation,’ I assure you, has from this moment begun. (79)

Isn’t her over-the-top rhetoric just delightful? A hundred years before feminists were accused of burning their bras, these “cruel steels” were lording it over the “abdomen and thorax.” And now look at us: emancipated, both from wearing corsets, and from having thoraxes (thoraces?).

Bodice Ripping

No corset stood out to me more as a kid, though, than the one Elizabeth Swann’s father gifts her in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl. “I hear it’s the latest fashion in London,” he tells her. “Women in London must have learned not to breathe!” she shoots back.

Later, the corset constrains her breathing so much that she faints off the fort’s parapet and almost drowns, surviving only because the pirate Jack Sparrow cuts her out of the garment.

The irony, of course, is that even as Jack Sparrow saves her life, his actions are seen as violent – and sexual.

To modern viewers, the corset - with its tiny waist, pushed-up breasts, and breath constraint - is more lingerie than foundation garment. Not for nothing do we nickname sexy romance novels “bodice rippers,” with their promises of dramatic removal (whether by knife like Jack Sparrow, sword like Zorro, or - improbably - the hero’s bare hands).

Ironically, while Rose’s mother was lacing her into her old-school corset, a few cabins away another passenger was on the cutting edge of innovation. Lady Lucy Duff Gordon (who gets a brief nod in Cameron’s film when Jack goes to dinner in first class) was a daring designer of lingerie for Europe’s wealthy and fashionable women. Lady Duff Gordon eschewed corsets as restrictive and boring, instead creating diaphanous, barely-there undergarments for her clients that were explicit in their intention to seduce.

While the practical aspects of corsets lived on in girdles, push-up bras, and other forms of shapewear, they came in and out of fashion as lingerie throughout the twentieth century. This lingerie website does a nice job of detailing those changes, if you’re interested.

It wasn’t until 1987, though, that fashion designer Vivienne Westwood decided to make the corset a symbol of rebellion. As Natalie Hughes explains, “It was a reclamation of female power, sexual and otherwise, and re-contextualised the corset from rarely-seen base layer to provocative outerwear piece.” Suddenly, corsets were punk.

Of Bodices and Battleships

Finding reliable sources for this research has been difficult. While several dress historians recommended Valerie Steele’s The Corset: A Cultural History (2003), I haven’t been able to get a hold of it yet, and the other books of fashion history I had access to at my public library were irritatingly shallow in their coverage of corsetry, if they covered it at all.

Bronwyn Cosgrave’s The Complete History of Costume & Fashion: From Ancient Egypt to the Present Day (2000), despite the ambitious promise of its title, only mentions corsets on five of its 256 pages. It traces a general chronology of the garment that appears again and again: Ancient Minoans wore laced bodices underneath their breasts (with, it would seem, nothing underneath or on top!), thousands of years passed, and then suddenly in the 1500s women started wearing corsets over shifts and did so in various forms and silhouettes until the beginning of the 20th century.

I have trouble believing, however, that Cosgrave is providing us with a truly comprehensive understanding of the corset, considering the author’s larger oversights and omissions: despite claiming to be the “complete history” of fashion, she entirely fails to mention any clothing outside of Europe and the United States between ancient Egypt and World War I!

The internet, of course, can provide us with information easily and with great depth. This website for a group of Wyoming-based historical re-enactors provides an incredible wealth of paintings, fashion plates, and artifacts that you could spend hours looking through. The Victoria and Albert Museum also has hundreds of corsets and fashion plates in its online collection. I highly recommend checking these sites out if you share my interest in rifling through the underwear drawers of history.

At the same time, however, internet histories of the corset frequently trade accessibility for accuracy. The Wikipedia page about the history of the corset, for example, claims that corsets fell out of fashion because of World War I: “Shortly after the United States' entry into World War I in 1917, the U.S. War Industries Board asked women to stop buying corsets to free up metal for war production. This step liberated some 28,000 tons of metal, enough to build two battleships.” I found several other sources repeating this story - including an NPR article! - and citing the same source: a family history page about May Phelps Jacob, whose descendants claim invented the modern bra.2

While I will save the equally murky history of the bra for another day, it’s worth noting that this history page does not directly cite any primary or secondary sources for its World War I claim. It also unquestioningly repeats several common errors about corset history, such as the myth that corset wearers regularly tight-laced down to 16 inch waists, leading me to take it with a significant helping of salt.

On one Mythbusters fan forum, in which the original poster was investigating the same World War I claim I was, someone did the math and concluded that each woman in the United States would have to forfeit eight corsets in order to come up with the metal to build just one battleship. So - almost certainly a myth.

But it’s such a nice, neat, seductive story, isn’t it? Those silly historical women removed the foolish garments of the past, and traded them for modern victory.

Shaping History

This week I set out to write a newsletter about the history of corsets, and ended up thinking more about the inaccessibility of the past, and the narratives we like to lay over top of it. In much the same way that the silhouettes of corsets shifted throughout history to match changing ideals, people have continually reshaped the story of the corset to fit their own agendas.

For feminists, the corset is a literal cage, forcing women to conform to the male gaze and preventing them from bodily and societal freedom.

For its admirers, the corset is a symbol of fashion and sexuality, exaggerating the shape of women’s bodies and paradoxically promising both restraint and fecundity.

For those critical of the body positivity movement, myths around corsets and historical waist sizes support a narrative that fat people are a recent phenomenon, an abandonment of a long-established standard. Fat people, of course, have always existed, and they wore undergarments too: I really enjoyed the images included with this set of practical construction tips from a historical sewing website.

Finally, in recent years, with the growing online popularity of Renaissance Faires and historical costuming, I’ve seen efforts to reclaim the corset as normal, comfortable, and even preferable to contemporary undergarments. One of the most popular, and persuasive, of these advocates is YouTuber Bernadette Banner:

Most of the points Banner makes here - that the average corseted waist size was quite reasonable, that women were able to breathe just fine, that the smallest corsets have survived because they were reworn by fewer people - are claims I have found across multiple reputable sources.

This video stands out to me, however, because Banner claims to speak from the authority of growing up wearing a corset herself.

Banner and I, it turns out, have this experience in common: we both spent our early teen years wearing corrective plastic braces to treat scoliosis. “Had I not been explicitly told to do so, I would honestly probably still be wearing it today,” she enthuses regarding her brace. “I loved it…it was extraordinarily comfortable.”

Here’s the thing: I hated my brace. It was cumbersome, and stiff, and made it difficult to breathe. The tank tops I had to wear underneath it always ended up soaked with sweat. On hot days, it felt like my entire torso “fell asleep,” going numb and then being pierced by a thousand pin pricks.

Sometimes I still have nightmares that I am wearing it. In those dreams, I always pull off the brace and then destroy it, by throwing it down a hill or smashing it with a sword. It has been sixteen years since I was allowed to stop wearing that brace, and still the feeling of it haunts me.3

Which one of these conflicting narratives should you trust more? If our experiences are truly authoritative as to the nature of corset-wearing, were they comfortable and supportive garments or symbols of perpetual torment?

On this question of authority, Banner and I actually agree.

“I think the one thing we can actually definitively conclude,” she muses, “at this place in time in regards to the social, cultural, psychological, physical effects of Victorian corsetry - no matter how much research we do and similar personal experience we may have had - we’ll probably never really fully understand them.”

The Past Is a Foreign Country

L. P. Hartley famously quipped that “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” After more than two thousand words of movie recaps and historical rabbit holes, is this where I leave you - with a somber proclamation that we will never understand corsets or their wearers?

While, of course, we can never fully access the past, I generally subscribe to the belief that our ancestors were far more like us than we often might think. As dress historian Hilary Davidson protests in Smithsonian Magazine, women were just as diverse in their needs and attitudes during the age of corsets as they are today. Working-class women wore comfortable, flexible bodices analogous to today’s sports bras and bralettes; meanwhile, every era has a handful of “influencers” who force themselves into elaborate, architectural contraptions for the sake of fashion. “For Davidson, the myth that women ‘walked around in these uncomfortable things that they couldn’t take off, because patriarchy,’ truly rankles,” Rachel Kaufman reports. “‘And they put up with it for 400 years? Women are not that stupid.”

In all my historical fiction viewing, I can honestly say that my favorite depiction of the corset - or, more accurately, stays - is on the show Outlander. The show takes Hartley’s framing of the past literally, following WWII-era nurse Claire Randall as she inadvertently travels to 1740s Scotland and struggles to return home. Outlander is known both for its beautiful costumes and for its explicit sex scenes, and as a result we spend lots of time seeing 18th century people in various stages of dress and undress.4

In Outlander’s second episode, housekeeper Mrs. Fitz unceremoniously exchanges Claire’s comparatively skimpy 1940s dress, bra, and slip for their 1740s equivalents: a shift, wool stockings, stays, bumroll, petticoats, and finally a skirt and bodice. This collection of elaborate yet practical undergarments are what Claire wears throughout most of the first season, and they never prevent her from riding horses, treating injuries, or otherwise having adventures.

After Claire marries the hunky Jamie Fraser several episodes later, we get to see the fancier version of 18th century undergarments that she wears under her wedding gown. On their wedding night, Jamie removes all of those layers of clothing, one at a time, including carefully unlacing her stays. The scene is sexy, but also methodical: Claire’s bodice is far too valuable to be ripped!

As Outlander crosses oceans and centuries, its corsets remain simultaneously sexy and practical, much like the underwear we wear today. One other ensemble, though, stands out.

In season three, Claire has the opportunity to use modern technology to build an eighteenth century traveling gown. She includes a linen blouse, water repellant separates, and many concealed pockets. And - given the choice to go without - Claire still decides to wear a corset.

This corset, however, has one modern alteration (much to Jamie’s relief): a zipper.

When it comes to corsets, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

This newsletter does not in any way support Chris Brown, but I couldn’t resist the joke

Well, it did claim that. It also misquoted Elizabeth Stuart Phelps Ward. I’m planning to update it later this afternoon.

To be completely fair, however, my wedding dress also featured a corset. Not only was it both sexy and immensely supportive, but it was also a major reason why I spent my wedding day miraculously without any back pain

Season 1-4 costume designer Terry Dresbach used to have a fantastic blog about the show’s costumes, which seems to have disappeared from the internet. I managed to dig it up through the Internet Archive, if you want to lose several hours.

I appreciate this article and the reiteration of the idea that people in the past are really not that different from us today.

One of my favorite tangents to the "corsetry as oppression" discussion is how so many early photographs have been "Photoshopped" to have smoother skin and smaller waists. The lovely Bernadette has a video on the topic. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gYGUfg_NJzg&t=3s

I just wanted to add that corsets feature pretty heavily in the world of drag, or at least the world of "RuPaul's Drag Race". For a "Death Becomes Her" runway, one queen wore an incredibly tight corset with an oxygen tank accessory. It's become one of the most iconic looks in the show's history. https://youtu.be/ew0WcDv3J0Q?si=4F6IrUBLowIybVKp