ON: Cookbooks

What's cookin', good lookin'?

Song of the Week: “That’s Amore,” by Dean Martin - When the moon hits your eye like a big pizza pie that’s amore”

Anyone who has spent any amount of time looking for a recipe online has no doubt encountered the frustrations of the recipe blog: if you want to learn how to make “SUPER EASY BEST EVER HUMMUS WITH JUST FIVE INGREDIENTS,” or “ooey gooey vegan dark chocolate brownies,” you have to scroll past an extended monologue about the author’s childhood, vacation, TV habits, and/or husband before you get to the recipe itself (which may or not be written accurately, and may or may not work).

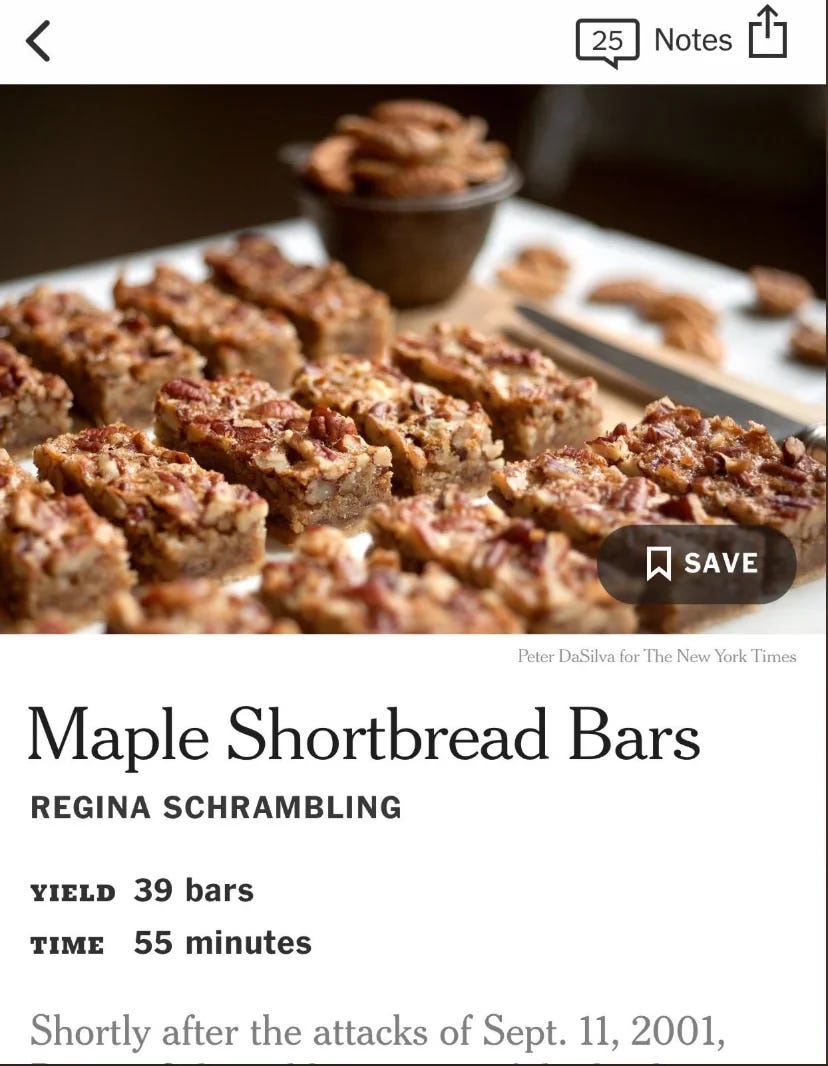

Even the New York Times Cooking - my favorite reliable online source of recipes - is occasionally guilty of it, as seen in this recipe that went viral.

While there are practical reasons why so many recipe blogs include rambling personal anecdotes - the longer you have to scroll to reach the recipe, the more ad revenue they receive - that doesn’t make those personal stories less annoying.

That’s why it’s ironic that I recently picked up a cookbook exclusively for the rambling anecdotes.

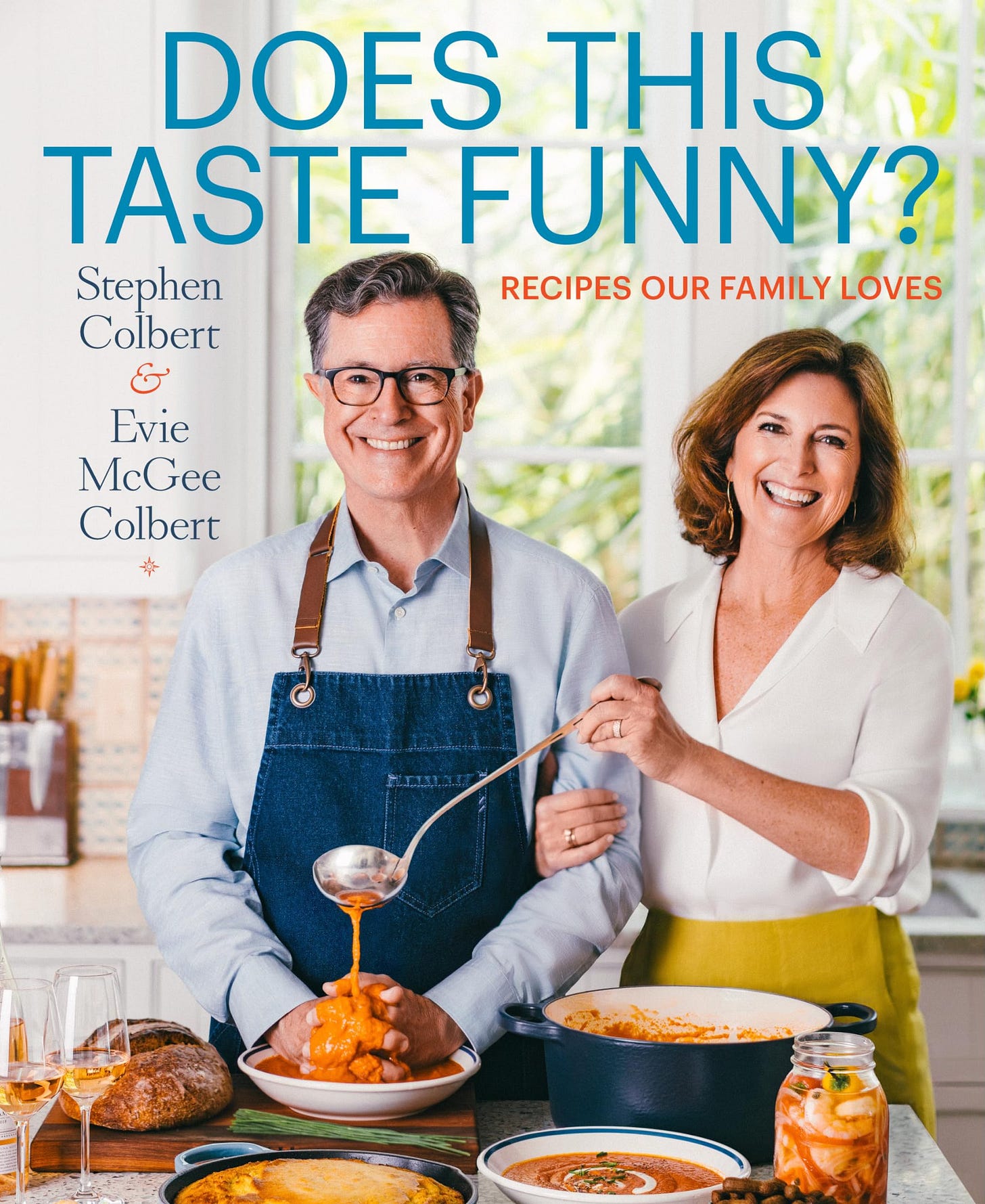

This month, I was lucky enough to be the first library patron to get my hands on a copy of Does This Taste Funny?: Recipes Our Family Loves, by Stephen Colbert and his wife Evie McGee Colbert. I’ve been a fan of Colbert for a long time - and not just because he’s such a high profile Tolkien fan! - but I hadn’t mentally put him in the same category of celebrity foodies as, say, Stanley Tucci.1

The Colberts’ cookbook - like most contemporary cookbooks - is a beautiful book: filled with colorful photographs of the food and sun-soaked portraits of the couple laughing on a picnic blanket or tasting from a wooden spoon.

What drew me to it, however, is the text, which is framed as a playful dialogue between Stephen and Evie. They banter, contradict each other, and tell rambling stories about the origins of these recipes, which come from their families, friends, and marriage. If one of them loves an ingredient featured in a recipe, and the other hates it, that disagreement serves as the introduction. Evie teases Stephen that his great sources of comfort are rewatching Lord of the Rings and making salt-and-pepper wings. Stephen complains that his siblings can’t decide on whose version of the famous Colbert fudge is the most authentic - and then provides all four duelling recipes for the reader’s discretion.

I read Does This Taste Funny? from cover to cover in two sittings, despite the fact that I will likely not make any recipes from the book. That shouldn’t be surprising: both Stephen and Evie are from the South Carolina Lowcountry, and the book is dominated by recipes for meat, seafood, and other southern-style favorites.2

Despite my aversion to shrimp, however, it will be a long time before I forget Stephen’s childhood story of going shrimping with his dad, who died tragically in a plane crash along with two of his older brothers when Stephen was ten. After a long day without catching anything, it began to rain, and suddenly father and son were pulling up nets bursting with shrimp, which they deposited in their Coleman cooler:

We stood there laughing in the downpour, amazed at our luck. When the cooler was full, my dad told me to drain the water so we could fit in more shrimp. At ten years old, I didn’t know there was a drain plug, so naturally, I tipped the cooler to let the water out. I lost control of it and spilled all the shrimp back into the harbor. My father looked at the water, at the empty cooler, and then at me. I don’t remember him being angry. I don’t remember what he said at all, but I do know that I don’t know if I have always been so patient with my own children. All I remember was both of us worrying that no one would believe how many shrimp we had caught. (20)

The great pleasure of Does This Taste Funny? is that it feels like hanging out in your best friend’s cozy kitchen, watching her parents chop vegetables and tease each other while they make dinner together. It feels like a front row seat to what tangible, long-enduring love can look like: humour, storytelling, and “Patti McGee’s Cheese Biscuits.”

Genealogies

It should come as no surprise that - as a great lover of both food and reading - I love cookbooks. I love their glorious pictures of crispy golden pastries and rainbows of grilled vegetables. I love how large they often are, heavy with wisdom and hundreds of potential meals. I love the way they stand neatly in a row in my kitchen cabinet, like friendly aunts who won’t meddle in my decision-making but are happy to give their advice when I need it.3

Though I cook specific recipes from cookbooks relatively rarely, I am comforted by the wealth of knowledge they represent, there whenever I need it: generations of professional and home cooks who celebrated birthdays, fed hungry kids after school, and gave solace to the sick or grieving.

That’s the attitude that drove New Yorker Julie Powell, depressed and aimless in the years following 9/11, to start a blog documenting her attempt to cook her way through all 524 recipes in Julia Child’s enormous Mastering the Art of French Cooking in a single year.

That blog became a memoir, Julie & Julia (2005), which in turn became a Nora Ephron movie adapting both Powell’s memoir and Julia Child’s memoir My Life in France (2006).

This is a rare case, by the way, where the movie is better than the book: both because Meryl Streep is fantastic as Julia Child, and because of the lovely way it parallels how these two women use cooking as a vehicle for agency and self-actualization. As Julia Child gains confidence in her cooking skills and navigates the publishing world to bring French cuisine to the United States, Julie Powell recreates those same complicated, archaic recipes in a tiny apartment kitchen, filling her days with texture and discovery and joy. “I was drowning,” Amy Adams’s Julie reflects in the film, “and she pulled me out of the ocean.” Who hasn’t had a recipe - passed down in a family recipe file, or recreated as a memory of happier times - serve as a similar lifeline on occasion?

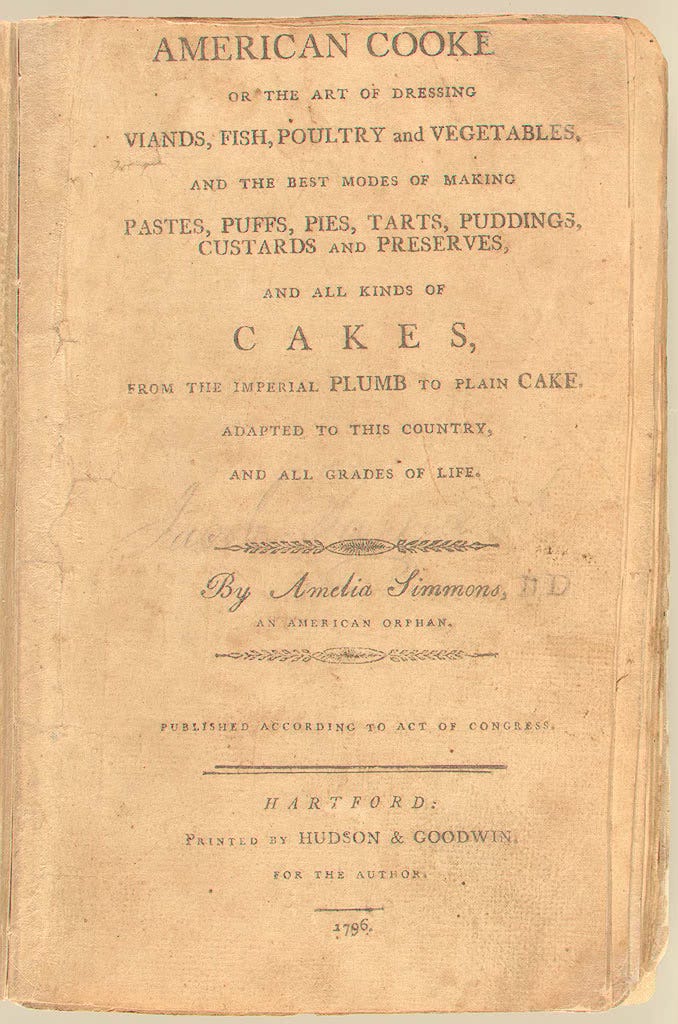

Though recorded recipes date back to 1700 BC in Ancient Mesopotamia - and there is a world of international cooking out there far too vast and multi-faceted to explore in a single essay - today I want to focus (mostly) on the American cookbook. I have, in my cookbook collection, a facsimile of the first American cookbook ever published: Amelia Simmons’s American Cookery, from 1796. This slim volume (only 47 pages!) promises to provide information on “the art of dressing viands, fish, poultry and vegetables, and the best modes of making pastes, puffs, pies, tarts, puddings, custards and preserves, and all kinds of cakes, from the imperial plumb to plain cake. Adapted to this country, and all grades of life.”

Simmons’s cookbook has one surprising thing in common with those contemporary recipe blogs: it begins with a personal anecdote about how she, an orphan, has had to fend for herself as a woman and a worker, and is sharing her culinary knowledge with anyone forced by circumstances to go into domestic service or feed their family. She establishes her authority not by describing her culinary school training or years of restaurant work, but rather by appealing to her exemplary behavior. “It must ever remain a check upon the poor solitary orphan…that the orphan must depend solely upon character,” she writes in the Preface. “How immensely important, therefore, that every action, every word, every thought, be regulated by the strictest purity, and that every movement meet the approbation of the good and wise” (4).

The cookbook’s next section is also quite familiar: a guide on how to shop for the best meat, fish, and produce. Some of the pieces of advice are still useful today - Simmons includes the tip to check egg freshness by whether or not the eggs float - but others are less so. Salmon, she warns us, should be “kept from heat and the moon, which has much more injurious effect than the sun” (6).4

Despite the book’s short length, Simmons crams in a startling number of recipes; aided, no doubt, by the fact that there are no illustrations or long descriptions of the dishes, and she often trusts the home cook to use their judgment on measurement, procedure, and cook time. Here, for example, is her entire entry for “Biscuit”: “One pound flour, one ounce butter, one egg, wet with milk and break while oven is heating, and in the same proportion” (38).

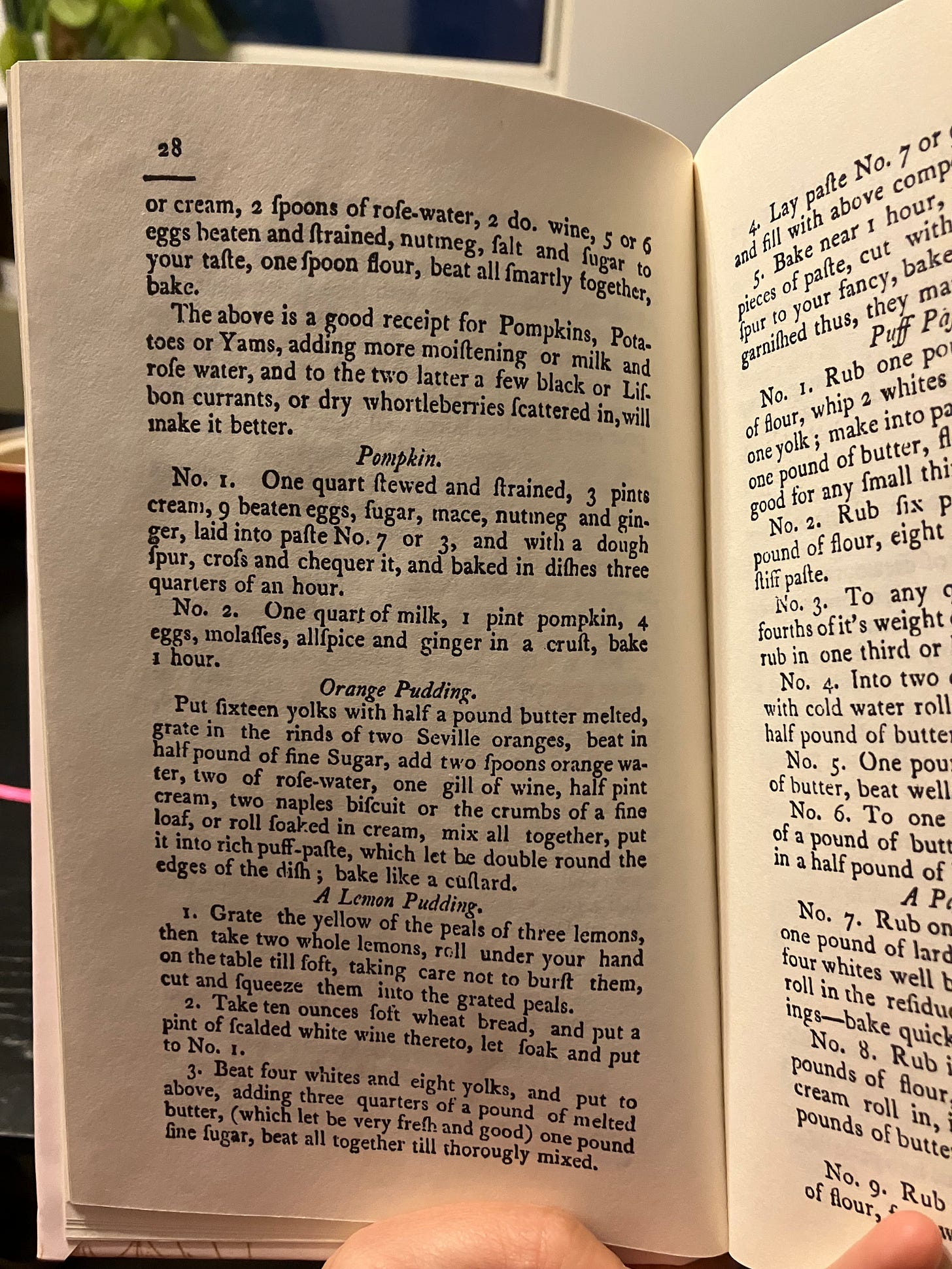

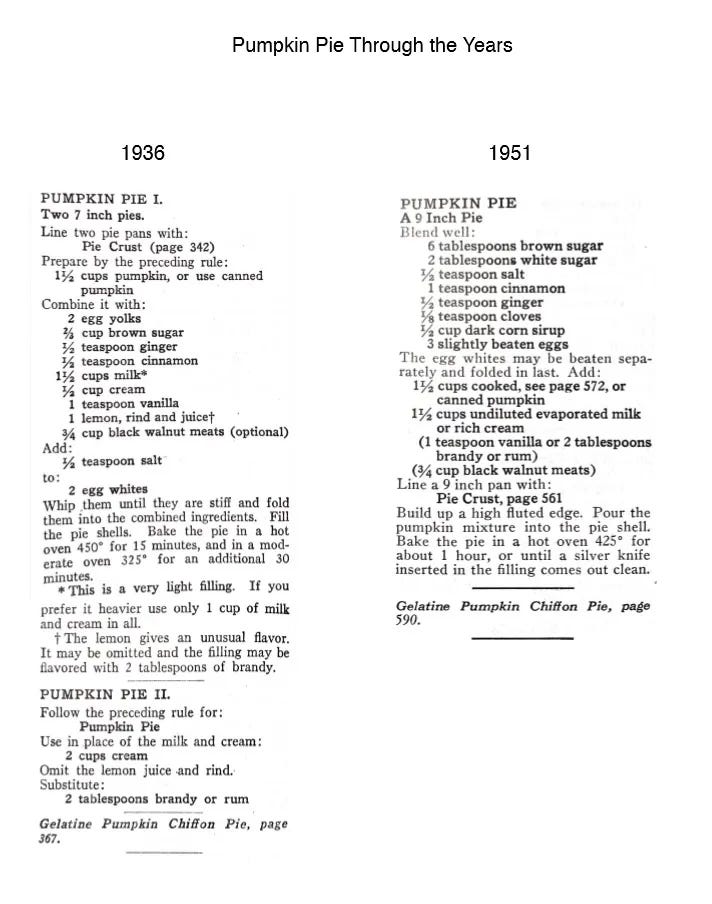

I thought about trying to make one of the recipes from American Cookery this week, but was scared off by the imprecision and the sheer amount of food these recipes make. Designed to feed large and hungry families, they frequently measure flour and sugar by the pound, and incorporate as many as a dozen eggs in a single dessert. I was particularly struck, however, by one recipe that appears throughout my cookbook collection, and thought it would be fun to compare them: pumpkin pie.

Like many contemporary cookbooks, Simmons simplifies her pie section by including a standard list of pastry crust (or “paste”) recipes, and then recommending how to use them in a variety of preparations. She has two recipes for pumpkin pie:

Simmons, of course, does not have access to Libby’s canned pumpkin, but otherwise, her ingredients list feels quite contemporary!

More than a century later, another resourceful woman down on her luck sought to write the definitive American cookbook. Irma Rombauer was a Missouri housewife who found herself in a financially precarious situation after her husband died by suicide in 1930 due to the onset of the Great Depression. Drawing on recipes from her family and friends, Rombauer published The Joy of Cooking: A Compilation of Reliable Recipes, with a Casual Culinary Chat (1931). That casual culinary chat, writes commentator Molly Finn, is why The Joy of Cooking was so enormously successful:

She engages in a constant dialogue with her readers, telling stories about herself and her family, sprinkling the text with genuine witticisms and excruciatingly corny puns, and making sure everybody knows that cooking is not an occult science or esoteric art, but part of the everyday work of the vast majority of women (and a few men) that can be turned into fun with her help.

Almost a hundred years later, The Joy of Cooking is still in print, albeit with numerous revisions: gone is its fanciful cover, which features St. Martha of Bethany, the patron saint of cooking, slaying “the dragon of kitchen drudgery.” The Depression-era instructions for skinning and cooking an opossum remain, but far more prevalent are recipes for dishes introduced by immigrants like pad thai, saag paneer, and pizza (which first appeared in the 1963 edition as “vegetable shortbread”).

The recipe for pumpkin pie that appears in my thrifted 2006 copy of The Joy of Cooking, however, is very similar to the earliest record I could find, from the 1936 edition.

Much like Simmons, Rombauer lists her pastry separately; unlike Simmons, however, some of her titular joy comes from the fact that she can conveniently buy her ingredients - including canned pumpkin! - at a full service grocery store instead of gathering them from the farm and market.5

Forty years after Irma Rombauer wrote sought to bring joy to the American kitchen, Julee Rosso and Sheila Lukins aimed to give it style. The friends and cofounders of the New York gourmet food store “The Silver Palate” published their 1979 cookbook of the same name in hopes they could share their recipes for chic, exciting food with home cooks across America. In The Silver Palate Cookbook they herald a new era in American cooking: one in which “we’ve watched a new quest for excellence take place in Americans’ attitudes towards foodstuffs. There is a sense of adventure, the redefinition of personal preferences. The curious become the passionate seekers of the new, the better, the best” (xiii).

They include detailed advice for how to throw stylish parties, along with sections explaining now-familiar foods: charcuterie boards, extra virgin olive oil, gazpacho. Rosso and Lukins do not claim to have invented or perfected any of these foods, but their role in popularizing them as part of American cuisine is undeniable. “Its recipes,” writes Julia Moskin in Lukins’s 2009 NYT obituary, “became dinner-party classics for a generation of modern cooks.”

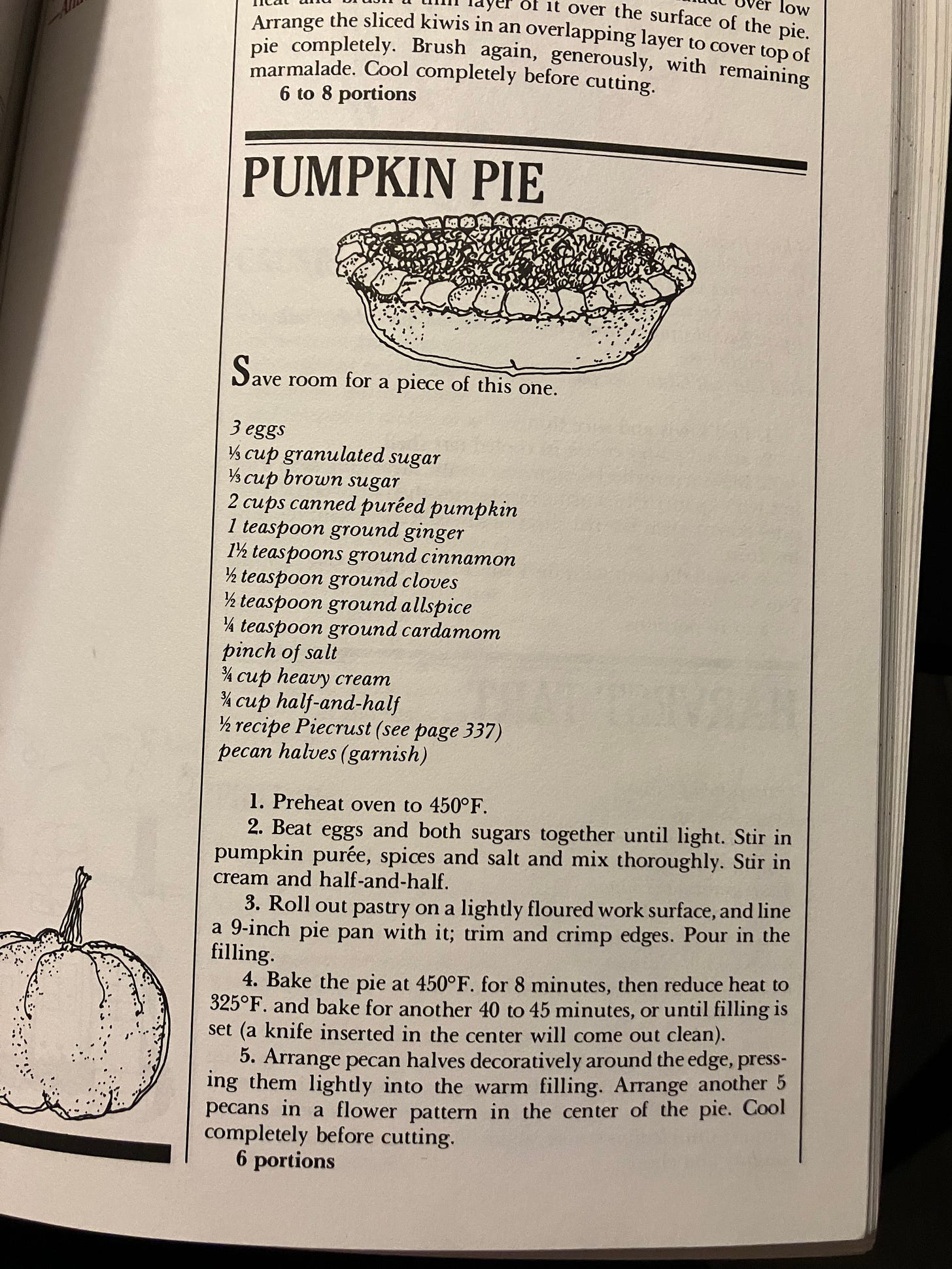

Nestled among these sophisticated, updated dishes, however, is a classic recipe for pumpkin pie, looking very similar to the one found in The Joy of Cooking. As the authors write - for The Silver Palate takes cookbook author-editorializing to a myth-making level - “The American tradition of freshly baked pastry is one we carry on at The Silver Palate” (303).

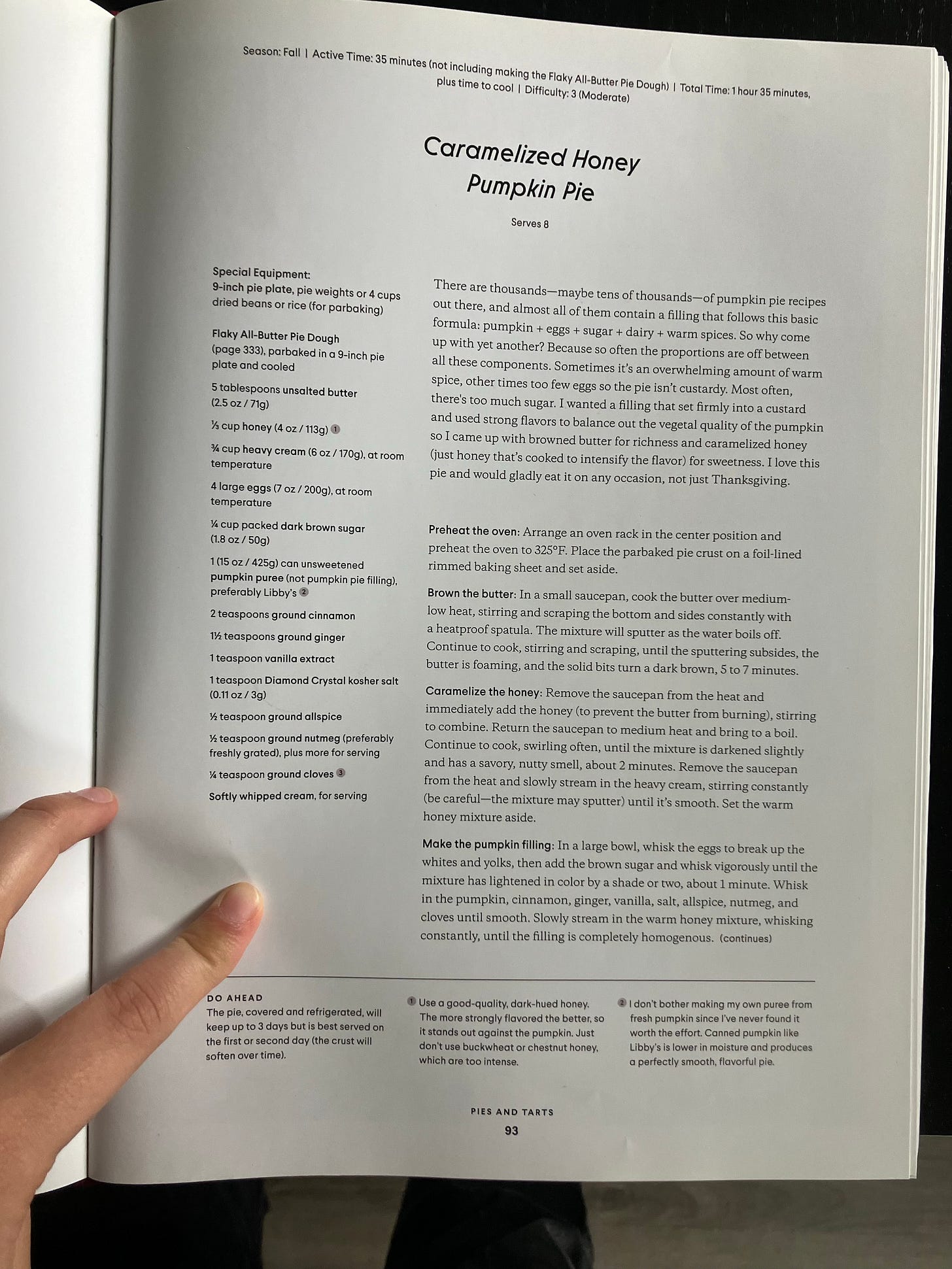

When I set out to make a pumpkin pie a couple weeks ago, however, I didn’t turn to any of these classics. Rather, I used Claire Saffitz’s sophisticated, extremely detailed Dessert Person (2020). Saffitz, a trained pastry chef, maintains the warmth of tone found in my previous cookbooks, but marries it to an intense specificity that makes her recipes somehow both more and less daunting than those found in The Joy of Cooking. Like all of the other pumpkin pie recipes, she also directs the reader toward a pie crust recipe written elsewhere in the book: unlike them, however, she gives directions for exactly how to cut the cold butter and incorporate it into the flour for maximum flakiness. She explains why certain formulations appeal more to her than others, introduces caramelized honey and brown butter for depth and complexity of flavor, and includes careful descriptions of what things should look like at each stage in the recipe.

Her recipes are intimidating, almost punishing in their detail. She leaves no element to chance, even making suggestions as to what brands of salt, flour, and butter will have the best outcome. And, I’m afraid to report, the result is the best pumpkin pie I’ve ever had in my life.

Melting Pot

Of course, there are alternative genealogies you can trace through American cookbooks to the one I have just followed using pumpkin pie.

Take, for example, the vegetarian cookbook: I have in my collection an original copy of The Vegetarian Epicure (1972), a book that - together with Diet for a Small Planet (1971) and The Moosewood Cookbook (1974) - provided home chefs with meatless recipes during an era when vegetarianism was seen as a fringe hippy lifestyle choice. Though these books’ hand-drawn illustrations and earnest tone are a far cry from the slick marketing and production values of modern books like The Veganomicon or Vegetable Kingdom, they share the same driving motivations and ethos: a desire to cook food that demonstrates respect for health, animals, and the environment.

Or you can point to the vast gulf between the cookbook as a form of community, and the cookbook as a way of cashing in on the latest trend. When I’m scouring the thrift store aisles for gems, I come across dozens of cookbooks making money off of our fads and anxieties: books for the Instant Pot or the air fryer, catering to the South Beach or Adkins or Paleo diets. By contrast, I’m thrilled whenever I encounter an amateur cookbook compiled for a fundraiser, women’s aid society, or church - a dying breed, full of nearly identical casserole recipes and names like “Betty’s Chicken Surprise” (the surprise is almost always a can of condensed soup). As commenter “mrs1II” writes on the r/Old_Recipes subreddit:

They contain cherished family recipes. Passed from generation to generation. They contain recipes specific to certain regions of the US. They include ‘Immigrant,” or ‘Old Contry [sic]’ recipes. Lovingly recreated, and prepared for generations…Home cooks only submitted their very best recipes for publication in fundraising cookbooks. Their family’s favorites. The ones required for gatherings where food was served. The ones who received “Oos and Ahs.” The ones met with mouthwatering anticipation. Recipes that were “reserved” for special occasions.

You attached your name to the recipes that you submitted to be published in that little book. They represented you.

Fundraising cookbooks are much more than they appear to be

Still another story can be told of marginalization, resistance, and diversity: the ways in which America “the melting pot” has seen so many different global cuisines be gradually embraced by its citizens, even as it still struggles with prejudice against the people who brought those cuisines to its shores.

There’s Bollywood actress-turned-food personality Madhura Jeffrey’s An Invitation to Indian Cooking (1973), which soon became the definitive guide to curries and koftas for non-Indian cooks. Marcella Hazan, often called the Julia Child of Italian food, gave America Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking (1992), including the bolognese recipe that I make with Beyond Meat and fresh fettuccine whenever I want deep comfort. And a whole generation of diverse chefs called out systemic racism and exploitation at culinary magazine Bon Appetit while creating their own fantastic cookbooks: Priya Krishna’s Indian-Ish (2019); Rick Martínez’s Mi Cocina (2022); Sohla El-Waylly’s Start Here (2024).6

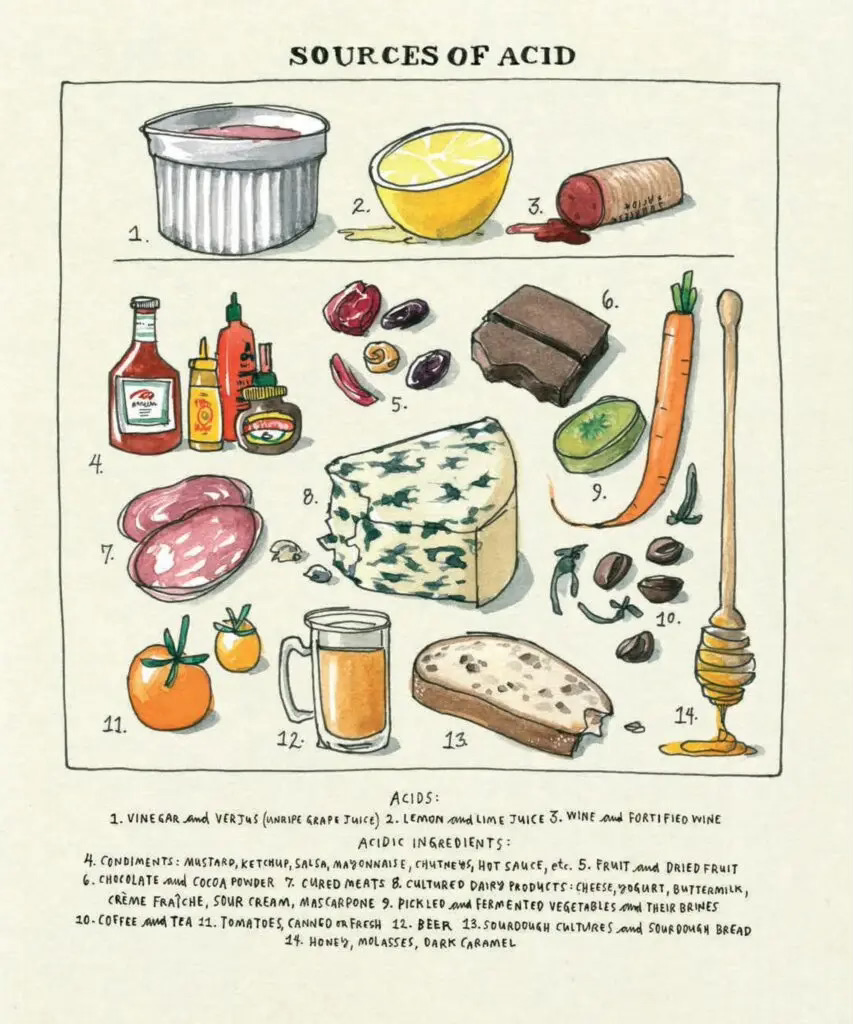

Finally, you can look at cookbooks not primarily as treasures of past wisdom, but rather as educations to encourage future creation. J. Kenji López-Alt’s The Food Lab (2016) explores the science behind cooking techniques and flavor combinations. Karen Page and Andrew Dornenburg’s The Flavor Bible (2013) is a reference book of ingredients, cross-listed with suggested flavor pairings and preparation styles. And my favorite cookbook of all time, Iranian-American chef Samin Nosrat’s Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat (2017) teaches you to cook through the application of the four titular principles. “These four elements,” she writes, “are what allow all great cooks - whether award-winning chefs or Moroccan grandmothers or masters of molecular gastronomy - to cook consistently delicious food. Commit to mastering them and you will too” (5).

Unlike a traditional cookbook, Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat spends half of its pages exploring how each principle plays out in different applications from food around the world before getting to the recipes. The playful watercolor pictures include practical illustrations (for example, of the difference between julienning and mincing vegetables) as well as charts of different ways one can incorporate the titular building blocks of flavour. Salt, for example, comes from tinned fish, capers, pickles, soy sauce, miso, cheese, nori, and more.

Thanks to Samin, I don’t shy away from using butter and oil to carry flavor, and I always add a dash of acid before adding more salt. Whenever I make roasted potatoes, I parboil them in water “as salty as the sea” first, resulting in crispy roast potatoes that are perfectly seasoned all the way through. Once, when my mother-in-law was browning ground beef for tacos, I suggested she add lime juice and fixed her complaint that it tasted flat without tasting a bite. Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat is that rarest of all cookbooks: it fundamentally changed the way I cook.

More than two hundred years after Amelia Simmons wrote American Cookery, Samin Nosrat returns me to its fundamental assumption: that - with practice - the experienced cook is comfortable enough to see the cookbook only as as a starting point, “equipped to trust your own palate, to make substitutions in recipes, and cook with what’s on hand” (5).

The Story of Being Alive

There is only one cookbook, however, that has ever made me cry.

Ella Risbridger’s Midnight Chicken (& Other Recipes Worth Living For) (2019) is, admittedly, a hybrid of cookbook and memoir. Risbridger opens, not with an introduction to common kitchen tools or basic techniques, but with despair: the author recalls lying on her floor, overwhelmed by depression, questioning whether she had any reason to keep going. “But this is a hopeful story,” she says. “It’s the story of how I got up off the floor. It’s also the story of how to roast a chicken, and how to eat it. This is a story of eating things, which is, if you think about it, the story of being alive. More importantly, this is a story about wanting to be alive” (7).

In Midnight Chicken, recipes are more narratives than science experiments, punctuated with beautiful descriptions full of care and attention. For example, in the instructions for Goat’s Cheese Puff with Salsa: “Lay two strips of ham across each pastry square, like this, like that, a delicate hammy kiss…Fold the corners of each pastry square into the centre, like you’re making a paper fortune-teller, only all the fortunes are cheese” (170).

Risbridger is the recipe blogger taken to the extreme, in the best possible way: she claims no culinary expertise, merely experience. “Stuck in a Bookshop Salmon & Sticky Rice” opens with a panic attack, then provides instructions to make the imagined dinner that motivated her enough to walk home. “The Tall Man’s Pâté,” made by the author’s boyfriend for a picnic shortly after they started dating, is not merely an amalgamation of alliums, dairy, and meat, but rather a marvel: watching him prepare it, she recalls, made her realize that “The scrubby, grim little kitchen of a Tiny Flat in the East End can be an absolute paradise, and everything in it tinged with glory, because for this minute we are alive, and looking, and that is as much as anyone can ask for.”

I don’t really care whether Risbridger’s recipes are the most precise, the most scientifically sound, the most optimized for freshness or sophistication or authenticity or flavor. She approaches food not with the heart of a scientist or a world-traveler, but of a poet. She understands that cookbooks are - first and foremost - accumulations of memory; guides on how to be a human, distilled from meals cooked again and again, by strangers and by friends. “Every time you’re in the kitchen,” she writes, “you’re alive with all the people whose books you’ve read, and the people who taught you, and the people who loved you. Nobody is born knowing how to cook. It all comes from people, breaking bread together, and talking, and loving, and sharing, and it is probably terribly trite, but I can’t think of anything more important than this.” (277)

When it comes to cookbooks, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

Why does mayonnaise have such a hold on Americans? A question for another Syllabus, perhaps.

And I particularly love thrifting them brand new for a fraction of their cover price!

Or rather, the “fun” - Simmons’ book has that delightful old-fashioned habit of using an f-like character for some of the s’s, which makes it difficult for modern readers to follow.

I thoroughly enjoyed this, it greatly resonated with me as I spend a lot of time recreating recipes through Pinterest and Tik Tok. It never really crossed my mind to look into more amateur cookbooks at the thrift store, but I will be keeping an eye out for them. I have made note of the cookbooks you've mentioned <3