Song of the Week: “L-O-V-E,” by Nat King Cole - “V is very very extraordinary”1

The most critical hour of the week for me, mental health-wise, is the hour immediately after Taylor leaves to drive back to Michigan.

If I don’t have an immediately distraction or project to throw myself into, it becomes far too easy to succumb to an extreme version of the “Sunday Scaries”, in which I feel sorry for myself, joylessly doom scroll on my phone, and have a self-indulgent little cry.

Perhaps that is the reason that, when I was sitting on the couch shortly after Taylor left at 8 p.m., and the thought “I should play Scrabble sometime” flitted idly through my brain, I pounced on the thought with the same fierceness and attention that my cat Minnie reserves for her favorite toys.2

Within five minutes I had downloaded the Scrabble Go app (somehow official despite an aesthetic resemblance to Candy Crush), and I then proceeded to play Scrabble non-stop till almost one in the morning.

It wasn’t a doom spiral, exactly, but I don’t know if it counts as mentally healthy behavior.

While the Scrabble-mania lessened somewhat out of necessity by the next day, the game has still been the defining feature of my week. According to the stats helpfully kept on my profile, I have played 28 games of Scrabble so far this week, almost all of them with strangers (many of whom, I suspect, are bots). I have won 18 of those games. My best score in a game so far is 392 points; my best word, the dubious “sulfury” (for a whopping 86 points, thanks to the 50-point bingo for using all seven of my tiles).

The appeal of the app is twofold: first, you can check words on the board to see whether they count, and how much they’re worth, making maximizing your score much easier.

Secondly, and more delightfully to me, you can have as many games as you want going at once. To me, the fundamental flaw of Scrabble - the reason I will choose different word games like Boggle or Bananagrams every time - is its slowness. I am impatient, and the distraction of multiple simultaneous games satisfies my impatience.

On Sunday night, as I gleefully played against seven strangers at once, I imagined myself as the protagonist of The Queen’s Gambit in that scene where she plays the entire high school chess club at once, and wins every game.

This, as it turns out, was hubris.

Super Scrabble

Some people, upon hearing about my new obsession this week, have nodded sagely: “Of course you love Scrabble, that makes perfect sense.”

Actually, this mania is new. Despite being a life-long lover of words, board games, and friendly competition, I have never been a huge Scrabble fan in the past, nor am I particularly good at it.

For me, as for most of my peers, Scrabble was one on a shelf full of classic board games that was pulled out on Saturday nights and Christmas afternoons. I have always associated the game with my father: he far outpaced anyone else in our family, and was punishingly slow about his turns, lingering over his letters until he finally placed them in a knot on the board, forming a handful of dubious two-letter words we had never heard of that somehow added up to dozens of points.

At some point, I started knitting while waiting for my turns; this annoyed him, but apparently not enough to speed up.

In 2004, Super Scrabble was invented, promising “more spaces, more tiles, more points,” and my dad dutifully brought it home. Super Scrabble introduced quadruple letter and quadruple word scores, and as a result he outpaced us even more dramatically. The games became even more torturously long.

In university, during the Words with Friends craze on Facebook, I challenged my best friend Jillian’s grandmother to a game in a rush of youthful bravado. She kicked my butt, of course: Violet Prouty was a legendary Scrabble player, and often played the game and its imitators for hours a day.

Around the same time, I played Scrabble with friends once at a party, and humiliatingly, I came third.

Thankfully, around this time European-style board games took off among my family and friends, and Scrabble was left to collect dust on the back of a shelf in favor of Blokus, Settlers of Catan, and Ticket to Ride: Europe.

Until, of course, this week.

On Monday morning, I roped Taylor into downloading the app. “Don’t criticize me too much,” he texted me, after playing his first word. No need.

This week, to Taylor’s amazement - and my mortification - he has beaten me at all three games we’ve played.

For a long time, my relative mediocrity at Scrabble has annoyed me. I’m a writer, after all. I have a PhD in English! Shouldn’t that translate to excellence at the most famous word game of all time?

Actually, no. Despite its appearance, being a great Scrabble player has very little to do with words at all.

A Nice Little Game

But first, of course, the inevitable origin story. This one, thankfully, is both quick and neat.3

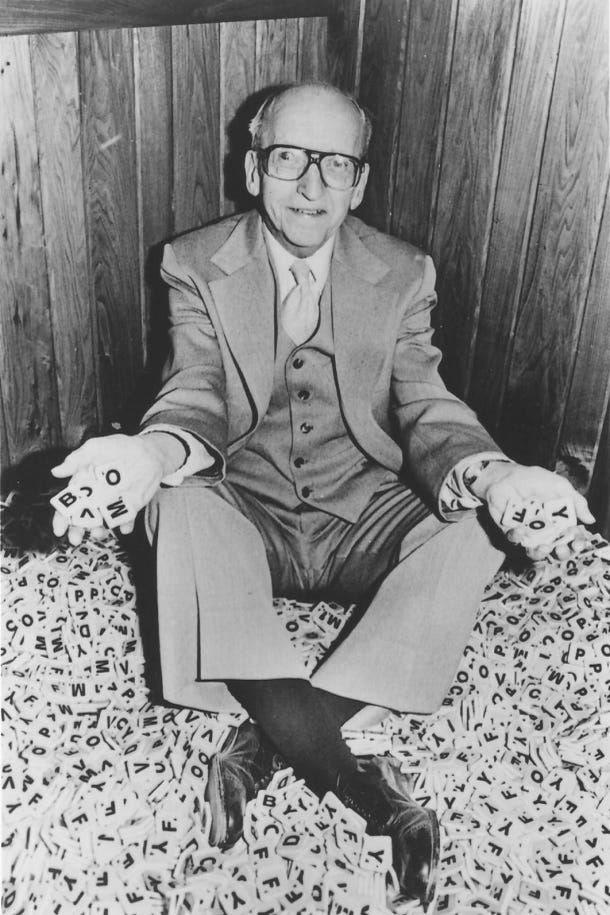

Scrabble was invented in 1938 by an American man named, delightfully, Alfred Mosher Butts.

Butts (heh) was an architect who, like so many others, ended up unemployed during the Great Depression. With a lot of extra time on his hands, he decided to create a game that combined his love of crossword puzzles with his love of anagrams.

Actually, he created two games: the first was a game named “Lexico,” from the Greek lexikos, “of or for words.” In Lexico, players drew from a pile of one hundred letter tiles with differing point values and attempted to anagram them into words.

Butts determined the relative frequency of different letters in the English language - and assigned them corresponding point values based on scarcity - by analyzing the front page of the New York Times. The result was the set of one hundred tiles - and corresponding point values - that we still use today.

Lexico, unfortunately, was not a success: both Parker Brothers and Milton Bradley rejected it. Butt kept playing with his Lexico tiles, however, and in 1938 he had the idea to add a 15x15 game board, on which players would place tiles crossword puzzle-style. He called his game “Criss-Crosswords.”

Butts playtested the game at his local church in Queens, New York, and paid to manufacture a few sets, which he sold to family and friends.

Unfortunately, Butts did not see much success from Criss-Crosswords, and ten years later, in 1948, in exchange for a cut of all future royalties, he sold the manufacturing rights to a Connecticut man, James Brunot, who had enjoyed the original game. Brunot made a few crucial changes: he rearranged the point value squares slightly, simplified the rules, and changed the name of the game to “Scrabble,” from the existing English word meaning “to scratch frantically.”

Brunot and his family started manufacturing sets and trying to sell them, but they lost money. According to legend, Scrabble’s big break came four years later, when Jack Straus - president of the department store Macy’s - encountered the game on vacation and played it with his family.4

Upon discovering that Macy’s didn’t carry it, Straus placed a big order. Brunot was unable to manufacture enough games to fill the order, and so he sold the manufacturing rights to Selchow and Righter, a game manufacturer that had previously rejected the game. “It’s a nice little game,” company president Harriet T. Righter said at the time. “It will sell well in bookstores.” 5

It did more than “sell well in bookstores” - two years later, in 1954, Scrabble sold four million copies. It went on to become one of the most popular and ubiquitous modern board games of all time, second only to Monopoly.6

According to most estimates I could find, Scrabble has sold 150 million copies worldwide: 33% of American households have a copy of Scrabble, and 53% of British households do. It is sold in 121 countries, and has editions in more than thirty languages, each with their own unique word distributions and point values.

Super Scrabble aside, the game has remained relatively unchanged since the 1950s.

Between 1984 and 1990, NBC did air a Scrabble game show, with the incredible tagline, “Every man dies. Not every man truly Scrabbles.”

For most of us, however, Scrabble remains a familiar if tired board game - and it might have remained as such.

If it wasn’t for the publication, in 1978, of the Official Scrabble Players Dictionary.

Word Slingers

It is unclear exactly when people began playing Scrabble competitively in clubs and tournaments, but by 1978, it was obvious to Selchow and Righter that Scrabble clubs needed an official record of every word allowed in the game. With the assistance of Merriam-Webster, the company compiled the dictionary by cross-referencing five popular college dictionaries of the time, excluding proper nouns, and including only words between two and eight letters. The Official Scrabble Players Dictionary (OSPD) is currently in its seventh edition, and it contains more than 100,000 words.

By contrast, the average native English speaker only knows 20,000 words.

So, if you want to be a Scrabble champion, at one of the world’s more than 4,000 local clubs or in one of its handful of international tournaments, what should you do?

Well, you can practice good “rack management” (setting yourself up with good remaining letters for your next turn), and you can play defensively, and you can memorize the list of 107 accepted two-letter words so you can maximize your scores.

But if you want to really compete with those top players? You’re going to need to memorize all 100,000 words in that dictionary.

This week I watched two short documentaries (both available on YouTube) about competitive Scrabble: the Canadian Broadcasting Corporations (CBC)’s 2002 Word Slingers, about a group of four Canadian players traveling to the 2001 World Championships in Las Vegas, and 2004’s Lost for Words, about four British players preparing for the Matchplay Championship in Exeter.

If you watch only one documentary about competitive Scrabble this week, let it be Word Slingers: the doc provides far more context on the mindset and rules surrounding competitive Scrabble, and it also features a narrator saying wonderful things like “A collective shake of the tile bags, the Scrabble equivalent of a starter’s pistol, and the World Scrabble Championship gets underway.”

Lost for Words, by contrast, is immersive but unfocused: it spends just as much time on one player’s flat tire as it does on the actual Scrabble Tournament.7

It was from Word Slingers that I learned that, at the elite level, Scrabble has nothing to do with being a prolific reader or writer. In fact, the best Scrabble players are often mathematicians and computer scientists. The Canadian mathematician Adam Logan, for example, won the World Scrabble Championship in 2005, and the Canadian Scrabble Championship five times. 8

Instead, players succeed based on their skills in math, their understanding of probability, and their memories: many of the world’s top Scrabble players have photographic memories.

At this level, knowing the definition of words is irrelevant, even distracting: rather, there are simply arrangements of letters that will score you points, and ones that will not. As a result, some of the world’s best Scrabble players are not even fluent in English: Thai players are particularly successful.

In between games, players spend hours flipping through flashcards, testing themselves on possible anagrams of seven letter word combinations, and re-reading the Official Scrabble Players Dictionary. While there are moments of camaraderie and celebration, especially in the social events surrounding the games, the matches themselves are often silent and serious. As Roxane Gay describes in her wonderful essay about entering an Illinois Scrabble tournament as a cocky amateur, “The more experienced players, the Dragos to my Rocky, studied word lists and appeared intensely focused on something the rest of us couldn’t see. Many wore fanny packs without irony - serious fanny packs bulging with mystery” (30).

At this level, competitive Scrabble doesn’t seem very fun to me at all.

Its top players, however, describe it in terms that border on poetry: as a love affair, a marriage, a vocation. As Canadian player Robin Pollock Daniel rhapsodizes: “Beautiful, beautiful game. It’s flowing, it’s mathematical, it’s musical, it’s architectural. It’s visual, spacial, it’s smart, it’s stupid, it’s dumb luck, it’s all of these things, it’s a confluence of clackety tiles, and I love it.”

“Now It’s Desirable”

Despite its popularity and intellectual nature, Scrabble doesn’t appear in fiction as often as other games. It lacks the pure strategy and elegance of chess, the flash and drama of Texas Hold ‘Em.

In one classic work of literature, however, Scrabble takes center stage.

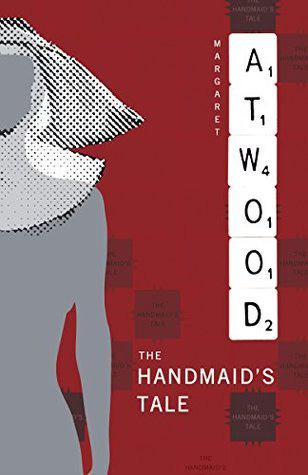

Margaret Atwood’s 1985 dystopian novel The Handmaid’s Tale is set in the near future, in a world where Christian fundamentalists have overthrown the United States and replaced it with a theocratic regime called Gilead. In Gilead, all women are forbidden from writing and from reading (even the Bible), and high-ranking men whose wives have failed to bear children are assigned fertile “handmaids.” The narrator of The Handmaid’s Tale, Offred, is one such handmaid, imprisoned and ritually raped by a man she calls the Commander and his wife, Serena Joy.9

Midway through the novel, the Commander instructs Offred to secretly visit him in his office at night, and she assumes that he wants her to perform illicit sex acts or otherwise act as his mistress. What he asks of her instead surprises her: he wants her to play Scrabble with him.

I hold myself absolutely rigid. I keep my face unmoving. So that’s what’s in the forbidden room! Scrabble! I want to laugh, shriek with laughter, fall off my chair. This was once the game of old women, old men, in the summers or in retirement villas, to be played when there was nothing good on television. Or of adolescents, once, long, long ago. My mother had a set, kept at the back of the hall cupboard, with the Christmas-tree decorations in their cardboard boxes. Once she tried to interest me in it, when I was thirteen and miserable and at loose ends.

Now of course it’s something different. Now it’s forbidden, for us. Now it’s dangerous. Now it’s indecent. Now it’s something he can’t do with his Wife. Now it’s desirable. Now he’s compromised himself. It’s as if he’s offered me drugs. (160)10

Unlike in tournament Scrabble, where words are reduced to accepted or rejected strings of letters, the words in this Scrabble game are of utmost importance to Offred. In a world where reading, writing, her name, and her voice have been taken from her, every word she remembers has power. In a regime that aims to control people through language, Offred’s wordplay throughout the novel represents her refusal to be conquered.11

I am grateful that, despite my passing obsession this week, the stakes of Scrabble remain low for me. I am not forbidden from playing, nor am I planning to spend any time and energy memorizing thousands of words in hopes of getting that perfect bingo.

As the week has gone on, my interest in playing against the strangers I easily beat has waned.

The only person I really want to play with, it turns out, is Taylor. In this era when we are so far apart, playing Scrabble together makes me feel like we’re connected. It has even become, dare I say it, a kind of flirtation. “That was supposed to be my triple word score!” he texts me over coffee on Wednesday morning. Later that day, I text him a genuinely admiring “nice job” over a clever use of space.

It’s nerdy, sure. But it’s fun. And I don’t mind losing to him at all.12

It’s a reminder that, after almost a decade together, he still has the ability to surprise me.

When it comes to Scrabble, what should I add to my Syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

There are two V tiles in a standard Scrabble game, each worth a base 4 points

The fabric belts stolen from my pants and shorts.

Unlike a game of Super Scrabble with my dad, ayo

Much of this history is taken from Stefan Fatsis’s Word Freak: Heartbreak, Triumph, Genius, and Obsession in the World of Competitive Scrabble Players (2001).

Harriet T. Righter is a fascinating figure in her own right. Her father, John H. Righter, co-founded Selchow and Righter in 1870. Harriet was active in New York’s social reform movement, worked on Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia’s campaign, and was a trustee of the Brooklyn Library. She became the president of Selchow and Righter in 1923, only three years after American women received the right to vote. She served as president until 1954, and died in 1982 at the whopping age of 104. She is remembered today mostly as the manufacturer of Scrabble

Last weekend, at a board game cafe, I saw a couple playing the horrifying Franken-game Monopoly Scrabble, in which players’ moves around the board are determined by their word scores. I should be thankful, I suppose, that this sighting inspired me to obsessively play Scrabble this week, and not the far inferior Monopoly. If you are interested, however, in the history of that game, which was also invented during the Great Depression, there’s a fun episode of The Anthropocene Reviewed about it.

Both documentaries feature people unironically saying things like “he’s the bad boy of competitive Scrabble,” which brings me no end of delight.

Logan is known for being extremely brilliant, extremely fast, and extremely late. In Word Slingers, a friend tells the story of how Logan showed up late to a tournament, hair still wet from the shower, with only four of his allotted twenty-five minutes left for a game. He won the game, with a score of over five hundred points.

Handmaids are stripped of their names, and referred to with names based on their assigned men - in this case, “Of-Fred.”

Offred has an improbably lucky game, judging by the words Atwood records her playing: she draws the Q, Z, and X tiles, as well as a V and all three of the Gs.

At least, that’s what I argued in my master’s thesis, which examined nonviolent resistance in The Handmaid’s Tale and Larissa Lai’s Salt Fish Girl (2002).

But mark my words, I will defeat him.

I wouldn't have a chance against you. Have you beat Taylor yet?

This topic certainly resonates with me. It warms my heart to hear you enjoying the game with Taylor.