Song of the Week: “Material Girl,” by Madonna - “‘Cause we are living in a material world / And I am a material girl”

Last week, at 7:30 p.m., I slipped into the bathroom of a grocery store and pulled a sequined miniskirt out of my backpack. After a full day of work and a stop at my beloved knitting circle, I was on my way to an underground reading rave: two hours of reading with strangers while a DJ played, followed by a dance party. The dress code included - among other imaginative descriptors - the term “Bibliopunk,” and I was going to do my best.

My grey oversized sweater vest and white linen button-down stayed, as did my chunky grey tweed loafers. But I switched my Old Navy chinos out for that sparkling silver miniskirt and a pair of black thigh high socks, and added ornate silver earrings shaped like snakes. A swipe of burgundy lipstick later and I emerged from the bathroom feeling like a new and much cooler woman, albeit with my work backpack unfortunately still in tow.

“I’m finally doing it,” I texted my friend Amy. “I’m ‘taking a look from day to night.’”

I was referring, of course, to the ubiquitous articles in magazines like Glamour and Cosmopolitan that we read as teenagers, with their promises of frequently having to go from our high-powered jobs as executives in New York City to hot dates or galas immediately afterwards.

When I was a teenager, I harbored a secret obsession with these magazines: their personality quizzes and advice columns, makeup tips and celebrity profiles. At home, I only read serious educational and news magazines: when I was thirteen, my grandmother bought me a subscription to Reader’s Digest!

But at the public library or the dentist’s office I’d surreptitiously flip through as many glossy magazines as I could, inhaling deeply and trying to catch the last whiff of Chanel No. 5 from ads for fine perfume. Later, in boarding school and then in university, I’d buy the occasional Teen Vogue or Cosmopolitan, reading it from cover multiple times before cutting it apart to make a collage for my binder. For years, I sprayed my perfume in a cloud in the air and then walked through it because one of those magazines told me to.

Part of me looked down on these magazines for their shallowness: for their focus on dating and makeup and fashion and gossip. But another part of me - a part I didn’t want to admit existed - desperately craved the life of sophistication, desirability, and effortless beauty they promised. Like the awkward protagonist of 13 Going on 30, I dreamed of being “thirty, flirty, and thriving.”

For years, I did not feel like I was very good at being the right kind of girl. And women’s magazines? Their specialty was the makeover.

Celebrating Femininity

I started thinking about the large and amorphous category that we call “women’s magazines” a couple of months ago. Unfortunately, like so many other things these days, it was because of the far right.

In 2019, husband-and-wife team Brittany Martinez and Gabriel Hugoboom launched a new women’s magazine called Evie. With a glossy yearly print issue and a regularly updated website, Evie features a lot of the same kinds of content that I grew up secretly reading in those magazines at the library: celebrity outfit rankings, makeup tips, and date ideas.

“In many ways, Evie is a departure from the legacy media culture that encourages women to engage in destructive behavior. Rather we strive to highlight proven paths to longevity and joy,” Martinez told Rolling Stone magazine in 2023. “We often take a unique perspective that is essentially lost in women’s media today. We help women embrace and celebrate their femininity, instead of seeing it as a weakness.”

Reading between the lines: Evie was created to recruit Gen Z women to the far right. If that wasn’t obvious from its description of Melania Trump as someone who “deserves status as an inspiration for women everywhere to dress themselves gracefully and tastefully,” its less conventional lifestyle articles reveal its political underpinnings as well.1

Evie has featured articles promoting mask and vaccine skepticism, explicit transphobia, and even Q-Anon conspiracy theories. Its biggest target, however, is birth control: both the print magazine and the website frequently include misinformation about the effectiveness and health impacts of hormonal forms of birth control.

Conveniently, Evie offers an alternative: the rhythm method. It encourages readers to track their fertility using 28, an app developed by Evie’s founders and bankrolled by right-wing billionaire and JD Vance supporter Peter Thiel. This means that Thiel and his allies have access to all of 28 users’ data: a dangerous thing in a post Roe v. Wade America.

Oh, and one other thing: Evie doesn’t contain advertisements. As it turns out, this refusal to accept third-party ads - far more than its insistence on women’s central roles as wives and mothers - is what actually sets it apart from other women’s magazines.

Material Girls

Last night at my knitting circle, I asked the women seated around the table what they thought of when they heard the term “women’s magazines.” After some deliberation, they agreed that they thought about magazines in two different categories: colorful magazines for sexy single women like Cosmo and Glamour, and magazines more focused on cooking, childcare, and home decor for older married women, like Martha Stewart Living or Good Housekeeping. “You get to choose,” one knitter quipped: “mother, maiden, or crone!”

While today we (and advertisers!) think about these two kinds of magazines as separate, however, they have the same origins.2

While publishers produced limited periodicals aimed at women in the 18th century, the 19th century saw the rapid expansion both of printing capabilities and female literacy in the United States. The result was a boom in magazines for women, with none more influential than Godey’s Lady’s Book (1830-1896).

Godey’s Lady’s Book included numerous features that we would likely recognize: letters from readers with feedback or requests for advice, how-to articles about proper manners and household maintenance, and reports on the latest fashion. It also featured a great deal of fiction and poetry: a trend that continued in women’s magazines for more than a century.3

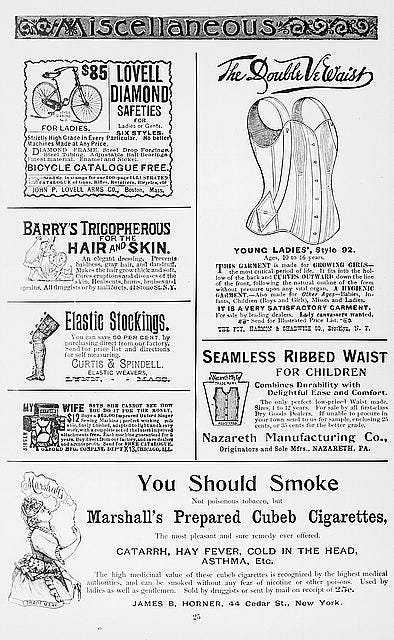

Most importantly, however, The Godey’s Lady’s Book contained advertisements. The Industrial Age was in full swing, and women were empowered to buy, buy, buy a dizzying array of offerings conveniently found within the Book’s pages: bicycles, children’s clothes, corsets, face creams, and even doctor-recommended cigarettes!

In the decades that followed, magazine after magazine was established following the Book’s formula. McCall’s, which lasted until 2002, was created in 1873 to sell sewing patterns. Ladies’ Home Journal, which ran from 1883 till 2016, advertised labor-saving devices and prefabricated items that would help make the homemaker’s life easier. This money-making strategy was enormously successful: for decades, Ladies’ Home Journal was the most popular magazine in the world, despite containing twice the volume of ads of any of its competitors.

By the 1940s and 1950s - often considered the golden age of women’s magazines - advertisements were the dominant feature of these publications. In some issues of fashion magazine Harper’s Bazaar, readers would have to get past over one hundred pages of advertising before they even reached the table of contents!

Though women’s magazines have gone through numerous shifts throughout the last two centuries, this one thing has remained constant: women’s magazines make their money by selling women consumer goods. As Nancy A. Walker writes in Women’s Magazines 1940-1960: Gender Roles and the Popular Press:4

The fact remains that the women’s magazines were - and are - businesses, and their dependence on advertising revenue for much of their income in turn meant that the editors took pains to avoid offending the manufacturers of soup, soap, deodorant, and washing machines…The pressure of advertising on editorial content…coupled with the magazines’ fierce competition with each other for subscribers - meant that the magazines remained reluctant to take on controversial subjects until those subjects had become fully accepted as part of a national conversation in which women readers might reasonably participate” (14).

As society changed, women’s magazines did too, though. With the onset of WWII, magazine publishers (and advertisers) discovered a whole new demographic worth marketing to: working women.

The Girl with a Job

When the United States entered World War II, every women’s magazine responded with content about how to support the war effort. This was no coincidence: the propaganda Magazine War Guide encouraged magazines to help readers “do their bit.” Articles advised on how to remake used clothing in the latest fashion, stretch rationed food with creative recipes, and invest in war bonds. More than anything else, however, women contributed to the war effort by entering the workforce: more than eight million women began working for pay during WWII. The magazines adapted quickly: a 1942 Good Housekeeping article, for example, features tips on “How a Woman Should Wear a Uniform,” instructing readers not to cut their hair short and look “mannish,” but to also avoid “luridly” painted nails or “frivolous shoes.”

One magazine, however, entirely reinvented itself to cater to these new financially and socially independent working women: Glamour.5

In 1939, Condé Nast created Glamour of Hollywood, a magazine filled with colorful photographs of movie stars and other elites, along with tips on how to emulate their lifestyles. Sales were sluggish; after years of Great Depression hardship, many readers had more pressing concerns than emulating the accessory choices of Vivien Leigh.

In 1941, however, Glamour of Hollywood got a new editor, the feminist Elizabeth Penrose, and became simply Glamour. Its new tagline? “For the girl with a job.”

Alongside articles on makeup and fashion were practical tips on college degrees, job applications, and potential career paths. As Gladys Schultz writes in a 1942 article for the magazine:

A hundred years ago there was no question about a woman’s place being in the home…Today it’s commonplace for women to plan cities, probe crime, produce plays, perform appendectomies, perfect patents and pay taxes - to say nothing of wearing pants. They sit on judges’ benches, in the President’s cabinet, at the head of large industries, at the helm of newspapers and magazines, and it’s as natural to them as breathing.

Of course, women had been working as the editors and writers of women’s magazines for decades. But for the first time, these kinds of careers were portrayed for readers as aspirational.

The war also took women to places they had never been allowed to go before - along with their readers. There is perhaps no better example of this than the case of Lee Miller, a model-turned-photographer who worked for British Vogue during WWII.6

Miller photographed air raid wardens, air force auxiliary volunteers, and nurses before eventually traveling to the front. Her pictures of the concentration camps after liberation became an essential part of the global reckoning with the horrors of the Holocaust - though they had to be published in American Vogue because the editors of British Vogue thought they were too shocking for their readers.

When World War II ended, millions of returning veterans needed to find jobs, and the Magazine War Guide responded by encouraging magazines to send women back home. Articles suggested that women look for more “feminine” work such as teaching and secretarial work, and warned against the dangers of delinquent children if their mothers didn’t pay them enough attention. In a 1951 Good Housekeeping article, Jennifer Colton explains “Why I Quit Working.” “One day,” she writes, “I realized that my office job was only a substitution for the real job I’d been ‘hired’ for: that of being purely a wife and mother.”

Advertisers did their part too, suggesting that their products would serve a crucial part in helping a girl find a husband to settle down with. In a series of ads for Lustre-Creme Shampoo, for example, the revitalization of a girl’s hair would inevitably lead to marriage within days. “I always thought of you as pretty,” the girl’s crush tells her, “but that new hair look makes you a Dream Girl…the girl I’ve always dreamed of finding.”

Glamour tried to hold out for a while, continuing its regular columns about how to be a working woman, but it didn’t last. In 1953, Elizabeth Penrose was replaced, and in 1956 the tagline changed to “the fashion magazine for young women - a guide to good taste at home, at play, on the job.” That same year featured a cover promising “special fashions picked to please men.”

As Walker writes, “...the idealized family of the 1950s was not the culmination of a long tradition; instead, it was a new phenomenon created by postwar America at least in part to celebrate democracy and capitalism in the face of the cold war threat of communism” (17-18).

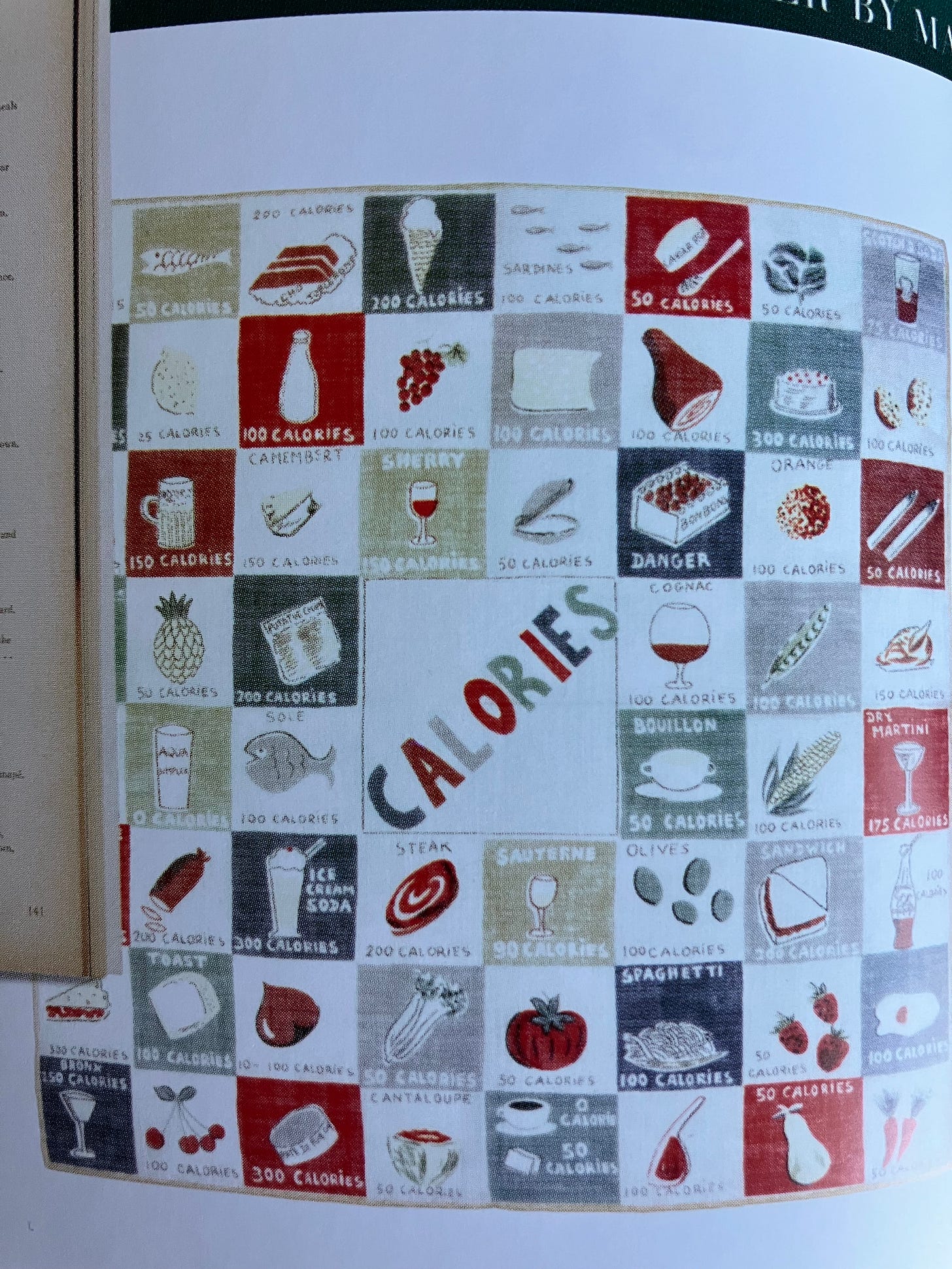

One other theme emerged in the 1950s, a theme that persisted so deeply that every woman at my knitting circle brought it up: weight loss. In the post-war world of caloric abundance, magazines switched from telling women how they could make their butter rations stretch further to shaming them if they ate “too much.” Articles advised women on how to choose girdles and bathing suits to cover their “problem areas” and offered exercises and diet tips to lose weight quickly and easily.

A 1952 issue of Glamour even advertised a convenient calorie-counting handkerchief - a proto-My Fitness Pal for the well-mannered set.

Though magazines left other 1950s mores behind, weight loss has remained a stubbornly persistent theme.

Even in the 2010s - at the peak of the body positivity movement - diet culture still persisted. As Brooke Erin Duffy notes in an article about “authenticity” in women’s magazines, Cosmopolitan and Glamour featured body diversity campaigns like Dove’s “Real Beauty” as well as images of models and readers of different sizes. Often, however, “an article/feature prompting women to celebrate their curves is sandwiched between images of tall, waifish models” (149). And, regardless of size, the reader is still encouraged to express her authentic self and personal style by buying clothes, makeup, and other products.

Now, distressingly, the fashions of the early 2000s is back - along with their toxic attitudes towards body size and weight loss. Much as in the 1950s, advertisers are caving to political and social pressures to promote conservative, constricting ideals of what a woman is allowed to look like.

After all, a hungry woman is more likely to consume.

Revolution

Not everyone, of course, bought what the magazines were selling.

While it’s easy to assume that everyone in the 1940s and 1950s subscribed to the attitudes depicted in glossy magazines, they had their share of contemporary critics. In a 1949 article for American Mercury, for example, Ann Griffith criticized women’s magazines as shallow and obsessed with never-ending consumption. “‘There, there, little women, leave all your thinking to us’ is about what these magazines tell their readers,” she writes. “To be advised on everything, from how much to nip in her waist this month to the proper attitude toward atomic energy is certainly easier for her than thinking for herself.”

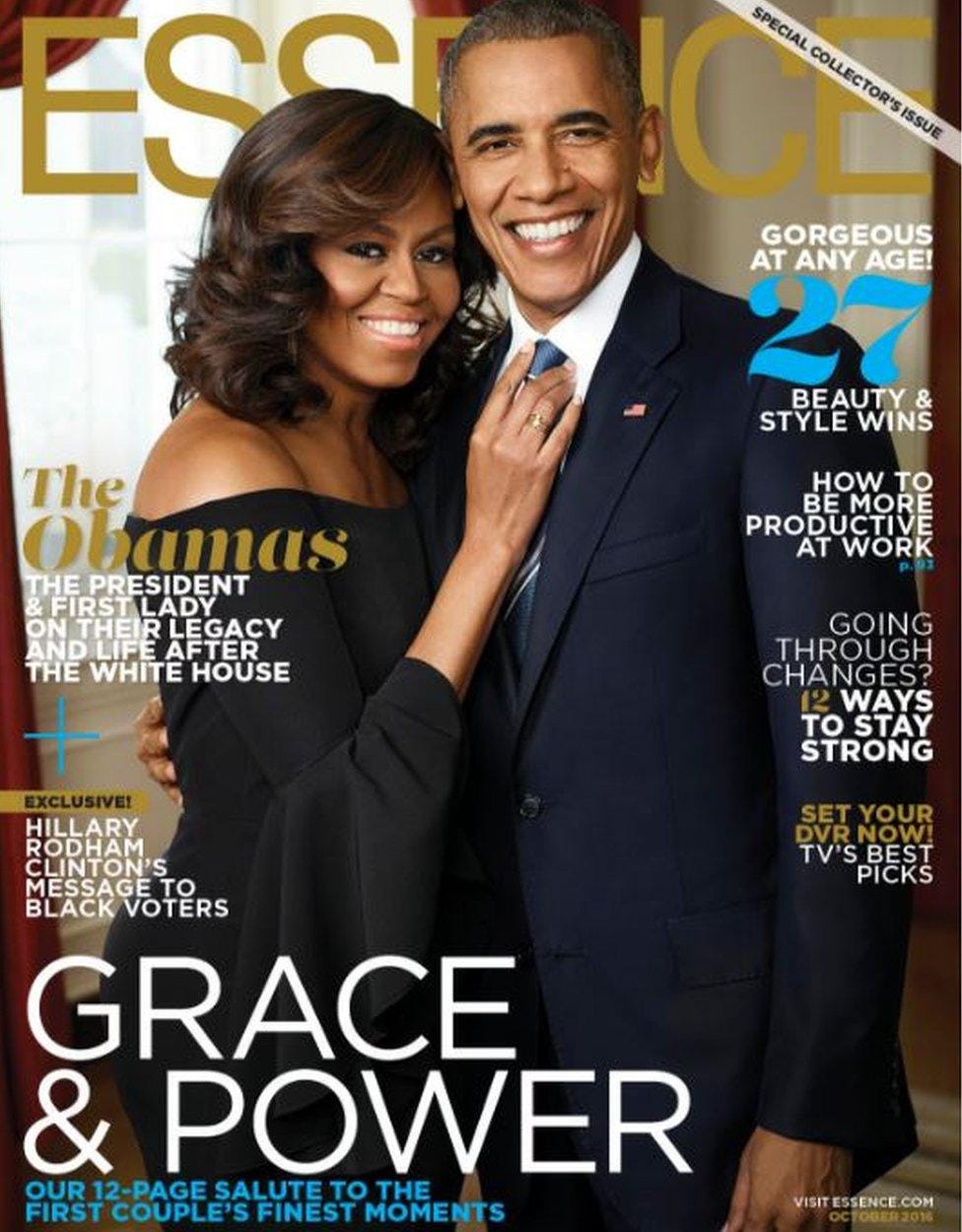

The 1960s brought a wave of social change that would alter the world - and the pages of women’s magazines - forever. The Civil Rights Movement demanded equal treatment and dignity for Black Americans; in response to the white supremacy held up as ideal by mainstream women’s magazines, four Black entrepreneurs founded Essence (1970). It featured styling tips for natural hair, interviews with Black actresses and singers, and articles that frankly discussed the difficulties of dealing with both racism and sexism in everyday life.

Meanwhile, the invention of the birth control pill ushered in the sexual revolution, and magazines like Glamour embraced single women’s newfound freedom. No publication did so more brazenly than Cosmopolitan. Begun as a literary magazine in the 19th century, Cosmo was reinvented in 1965 when Helen Gurley Brown - author of the controversial Sex and the Single Girl (1962) - took over as editor-in-chief. Her very first edited issue included a major feature on birth control pills and how to use them. As Brown’s New York Times obituary notes in 2012, “Unencumbered by husband or children, the Cosmo Girl was self-made, sexual, and supremely ambitious…she looked great, wore fabulous clothes and had an unabashedly good time when those clothes came off.”

Other revolutionaries of the 1960s and 70s believed that the problems with women’s magazines went beyond the limits of reformation. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963) argued that American women had been sold a false dream of proper behavior and fulfillment, in large part by advertisers and magazines. “The American housewife…was healthy, beautiful, educated, concerned only about her husband, her children, her home,” Friedan writes. “She had found true feminine fulfillment. As a housewife and mother, she was respected as a full and equal partner to man in his world. She was free to choose automobiles, clothes, appliances, supermarkets; she had everything that women ever dreamed of” (18).

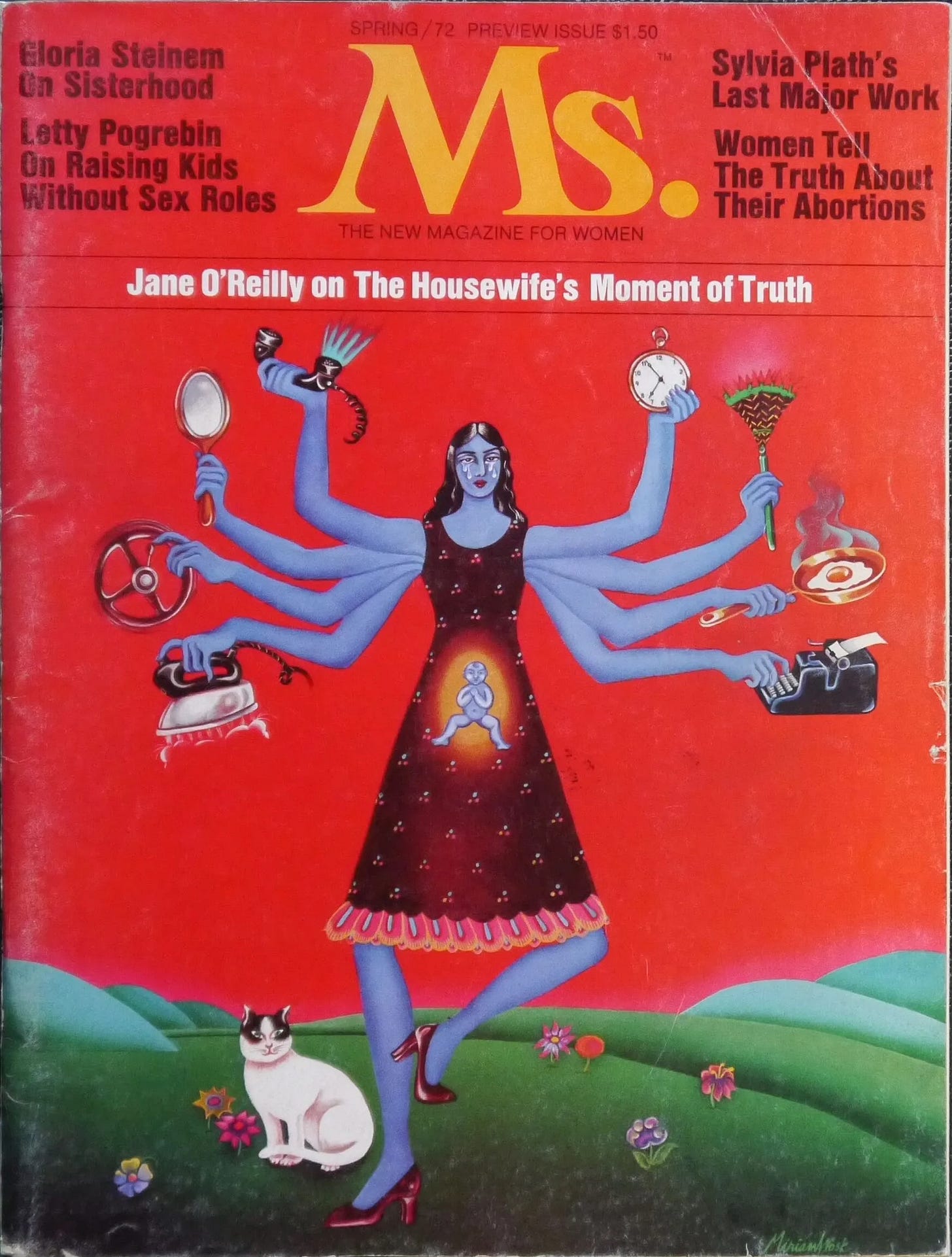

In response to the narrow and idealized vision of womanhood sold by women’s magazines, feminists created Ms. magazine.7

Founded by one-time Glamour contributor Gloria Steinem in 1972, Ms. aimed to be a voice and vehicle of the feminist movement. It featured frank articles on abortion, domestic violence, workplace sexual harassment, lesbianism, environmental destruction, labor conditions, and other urgent social issues. Though the magazine made missteps, as vividly illustrated in several episodes of the TV show Mrs. America, Ms. made a conscious effort to platform Black editors, writers, and public figures, including Audre Lorde, bell hooks, and Shirley Chisholm.

It also featured frequent letters and contributions from readers, such as this poem submitted by 9-year-old Anita Buzick II in 1975:

If you think I’m going to slave

in the kitchen for a man who is

supposed to be brave,

Then I’m sorry to say,

but you’re wrong all the way,

Because I’m going to be an

astronaut. Unsurprisingly, Ms. struggled to find advertisers who were willing to share space with such hot-button issues. Steinem and her fellow editors sought ads both for general “people products” such as cars, credit cards, and sound equipment as well as the clothes, makeup, and food that their readers expressed an interest in. Advertisers were turned off, however, by the fact that their ads would appear alongside serious political articles instead of recipes, makeup tips, or pieces convincing readers why they needed to buy another pair of shoes.

The companies who dared to advertise in Ms. saw their investments pay off, though. As one reader reported in 1975, “...those Honda folks put an ad in Ms. that talked about rack-and-pinion steering, and it sold me their car. The car is terrific, and the steering is even better, and I think you should know that I wrote them and told them to keep advertising in Ms.”

Despite some successes, Ms. consistently struggled due to the lack of advertising revenue. In the 1980s, they even reluctantly published ads by cigarette manufacturers, who were desperate for print avenues after being banned from television.

Finally, Ms. was purchased in 2001 by the non-profit Feminist Majority Foundation, and today it’s still providing a powerful platform for feminist writers and activists. Though they have little else in common, Ms. has learned the same lesson as the creators of Evie: it’s a lot easier to stay true to your political message when you don’t have to worry about advertisers.

To Be a Woman

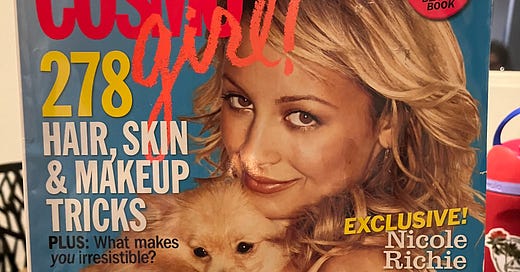

Last year, my friend Amy came to visit for the weekend, and in celebration I thrifted a 2005 issue of CosmoGirl for us to look through together.8

We expected ridiculous fashions, silly horoscopes, and problematic articles about body image, and there was no shortage of them. “Fuzz Busters” promised ways to say “buh-bye to unwanted body hair,” and “Work It” instructed readers on how they could use a hula-hope to get “a toned body.” But amidst the ads for lip gloss, anti-acne face wash, and temporary hair color, there were some surprises. A doctor bluntly and kindly answers reader questions about lesbian sex, STIs, and masturbation. A reader relates her struggles with being the caretaker for her mother who has advanced multiple sclerosis. Most impressively, a feature story sensitively shares - and completely legitimizes! - the experience of a Black trans girl.

Maybe if I had been a faithful reader of CosmoGirl as a teenager, I would have developed an eating disorder. Or maybe I would have figured out I was bisexual in high school. Who knows?

For two centuries, women’s magazines have been powerful vehicles of women’s culture, for better or for worse. Ladies’ Home Journal encouraged women to stay home and remain in unhappy marriages, but it also conducted important inquests into barbaric medical practices surrounding pregnancy and childbirth. Cosmopolitan and Glamour provided women with information about birth control, sex, and abortion, even as they taught them to never be happy with their bodies.

The contradictions of the women’s magazine are the contradictions of womanhood. As America Ferrerra’s character complains at the end of Barbie (2023): “ “It is literally impossible to be a woman. You are so beautiful, and so smart, and it kills me that you don’t think you’re good enough. Like, we have to always be extraordinary, but somehow we’re always doing it wrong.”

The truth is, these days, most of my nostalgia for women’s magazines is nostalgia for print media in general. Many of the magazines I grew up with no longer exist, or are a shell of their former selves. Glamour, for example, moved entirely online in 2018. Makeup tips, celebrity gossip, and advertisers have moved to TikTok and Instagram, where they’re reaching larger audiences than ever before.

I’m not saying you should only read serious articles from publications like Ms., or never indulge in a round up of sundresses for spring. I love celebrity crushes and colorful nail polish, and I wear perfume almost every day.

But when you do encounter the glossy, enticing imagery of the women’s magazine, in whatever form it takes next, make sure you take the time to think about what it’s really selling.

When it comes to women’s magazines, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

Another tell-tale sign? All of the sex tips are explicitly aimed at “wives.”

I’m only talking about American magazines today because they have a fairly well-defined lineage, and because as it is this research already got way out of control and reached almost 4000 words!

From 1837 to 1877 the editor was Sarah Josepha Hale, better remembered today as the author of “Mary Had a Little Lamb.”

All of the excerpts from historical women’s magazines in the rest of this essay are from this collection unless otherwise noted.

Much of this section is sourced from Glamour: An Extraordinary History (2024).

Is Vogue a women’s magazine? This, it turns out, is a contentious question. While Vogue has a lot in common with magazines like Glamour and Cosmopolitan, it has maintained a strict focus on fashion as well as a class status that sets it apart.

This section is sourced from 50 Years of Ms.: The best of the Pathfinding Magazine that Ignited a Revolution (2022).

CosmoGirl, a spin-off of Cosmopolitan for teenagers, only ran from 1999 to 2008, but it looms large in my childhood memories of those alluring magazines.