Song of the Week: “Eye of the Tiger,” by Survivor - “Risin’ up, straight to the top / Had the guts, got the glory”

For a large part of the last month, I - like billions of people around the world - have been thinking about, talking about, and watching the Olympics in Paris. I am not a big sports fan - I’ve only watched one Superbowl in my entire life, and don’t follow any other major sports throughout the year - but I love the Olympics.

Whether it’s watching Simone Biles defying gravity or learning about a bizarre sport I’ve never heard of, the actual sports are a pleasure to witness, of course.1

I have vivid memories of watching ski jumping in the middle of the night during the Turin Olympics in 2006 when I was miserable and up late due to strep throat.

My whole family - even my stoic, equally sports-ambivalent dad - were on the edge of our seats through the entire men’s hockey gold medal game at the Vancouver 2010 games. When Sidney Crosby scored the winning goal in overtime and won gold for Team Canada against the USA, we jumped to our feet and cheered, and through the window we could hear our neighbors doing the same thing.

Eight years later, I fell in love with the artistry and chemistry of Canadian ice dancing duo Tessa Virtue and Scott Moir, and spent hours learning about them and watching previous routines.2 When, in the last skate not only of the event but also of their entire careers, they skated their flawless routine to a medley of songs from Moulin Rouge! and won gold, I cried happy tears.3

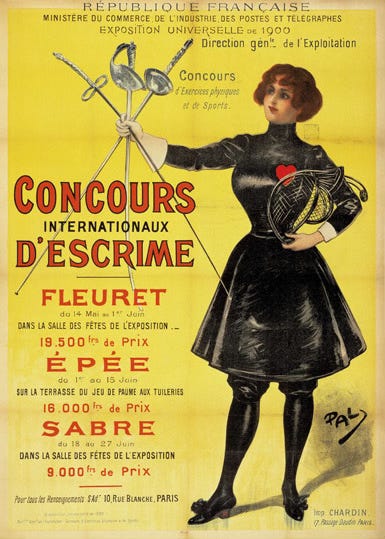

This year, I was particularly interested in the sports themselves because I pitched, wrote, and produced a video series about the math behind various Olympic sports for work. After months of corresponding with athletes and gym managers, doing research, collaborating with mathematicians, shooting and editing video, and creating graphics, we released videos about the math behind fencing, swimming, badminton, and rock climbing.

My favorite Olympic moments, however, don’t take place at a finish line or on a medal podium. My favorite moment always happens before a single medal has been won: the parade of nations during the Opening Ceremonies. Sure, I enjoy the pageantry, the flags, and the showcase of the different team uniforms.4

But whether I’m watching a few people from a tiny country proudly carrying their flag, or hearing the deafening roar accompanying a huge team, the highlight for me is always the same: I can’t get over the look on the athletes’ faces.

They are here. They made it. Every hour logged in the gym or the pool, every sacrifice of time and money, every injury rehabilitated and limit pushed, has led them to this moment. Before any starter’s pistol or competition or race or medal, they have already succeeded.

They have followed their dreams all the way to the Olympics, and they are so proud, and I am so proud of them.

Heritage

While the Ancient Greek Olympics, competitions in honor of Zeus that admitted only men, took place every four years for more than six hundred years (776 BC to 393 AD), the modern Olympic Games were founded in 1896.

They were the brainchild of Baron Pierre de Coubertin, a French aristocrat, amateur historian, and educational reformer who believed that sports and the arts were intricately linked, and both were vital to human thriving.

The first games, which were held in Athens from April 6 to 15, 1896, featured athletes from fourteen countries, and twelve sports: athletics, field events, cycling, fencing, gymnastics, shooting, swimming, lawn tennis, weight-lifting, wrestling, marathon, and discus-throwing. They were open to any man who wanted to compete.

A team of Greek athletes trained for months, determined to honor their country’s ancient heritage. By contrast, a group of American university students on vacation decided to register the day before the games, using their own sidearms for the shooting competition.

By the end of the games, the Greek team had won ten medals; the vacationing American college students, eleven.

This, by the way, was somewhat prophetic; today, the United States has a whopping 3,094 all-time Olympic medals, almost a thousand more than the next highest competitor, prompting many fans to quip that the real American national sport is winning.5

As this excellent episode of 99% Invisible explains, the first few Olympic games were informal affairs, often attached to world fairs or international expos, and featuring a baffling array of sports.

The 1900 Paris Olympics, for example, took place over a total of five months, and included both tug-of-war and firefighting. These Olympics were also the first ones to allow female competitors; of the roughly one thousand competitors, twenty-two were women, competing in five sports: tennis, sailing, croquet, equestrianism, and golf.

Another unusual feature of these early Olympics was de Coubertin’s insistence that they also feature arts competitions, meant to showcase “the essential thing of the Olympiad - that is to say the alliance of Sports, Literature, and the Arts.”6

Unfortunately for de Coubertin, the citizens of the world stubbornly remained far more interested in swimming, gymnastics, and track-and-field than they were in art competitions, and despite his protestations, major art competitions gradually disappeared from the game. The biggest relic of these art showcases, however, are the continuing contests that often precede the design of official Olympic branding.

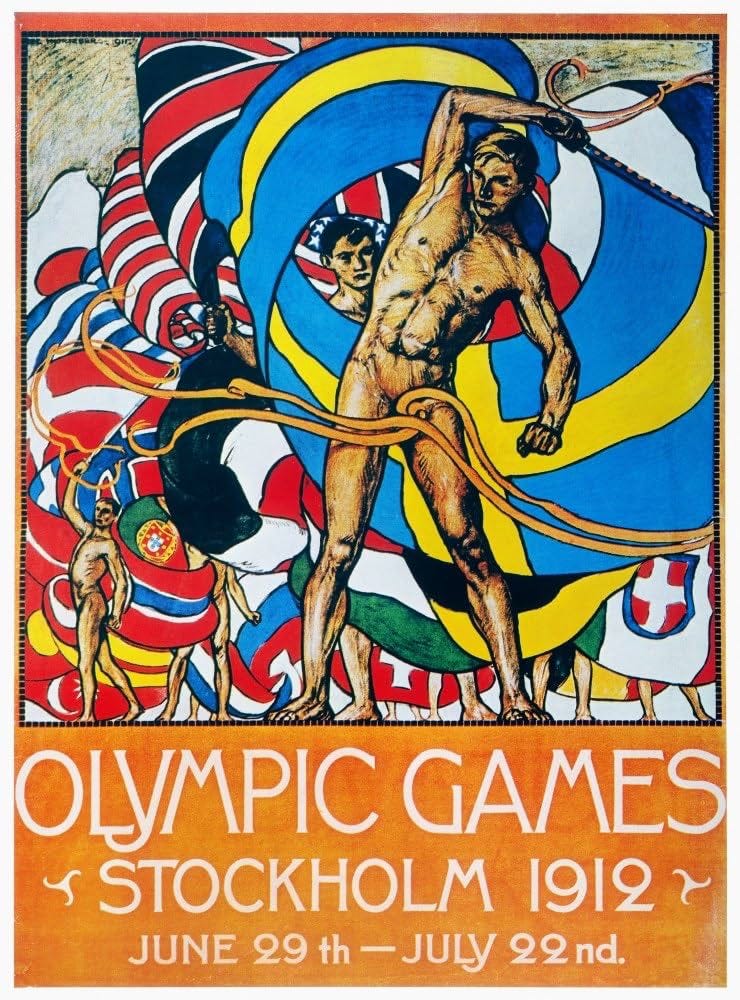

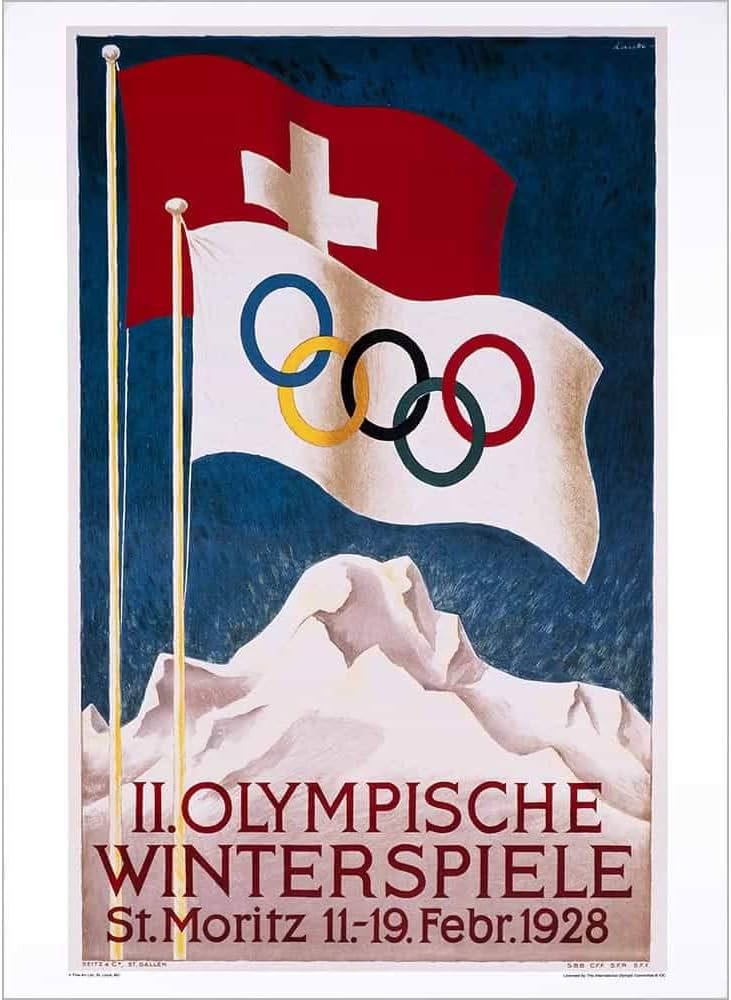

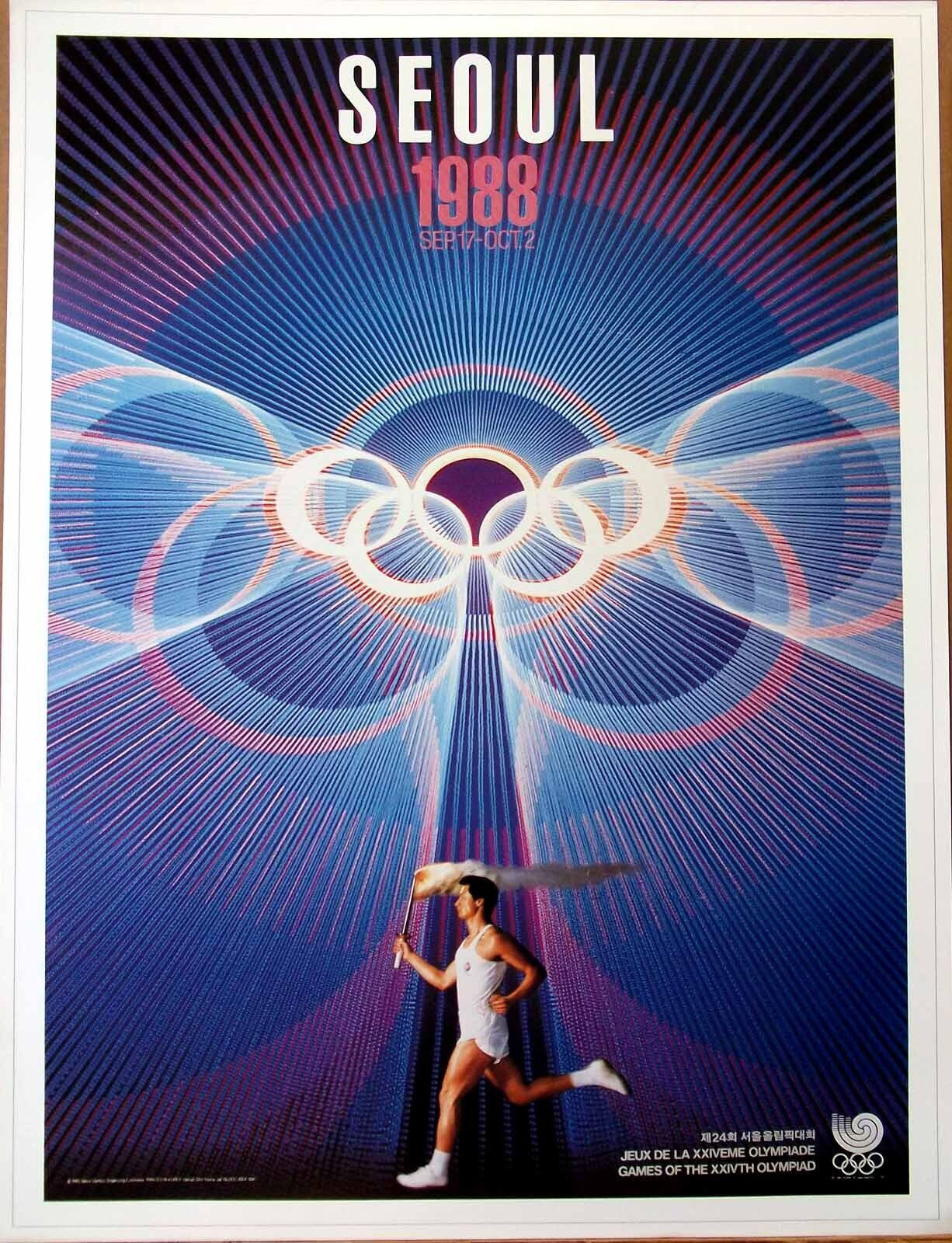

Margaret Timmers’s excellent book, A Century of Olympic Posters, commissioned by the Victoria and Albert Museum in honor of the 2012 London Olympics, recounts more than a century of Olympic history through the games’ iconography. I’ve scattered some of my favorites throughout the this week’s newsletter.7

“With their broad popular appeal and ability to relay messages through eye-catching and memorable imagery, they are effective both as announcements and as metaphors, whetting our appetite and shaping our expectations of the Games that are to come,” Timmers writes. “They offer Olympic venues as an opportunity to project to any international audience images that advertise, identify and define the event, and favorably influence how the venues themselves are perceived” (7).

The rituals and symbols that are now recognizable in the modern Olympic games were established in these early games, and popularized via these posters. The Olympic flag, for example, first appeared on an official poster for the 1928 Winter Games in St. Moritz, Switzerland.8

Despite their core messages of peace and international collaboration, however, the Olympics also faced major obstacles in the first half of the twentieth century. They were, of course, canceled twice: from 1914-1918 due to the outbreak of World War One, and again from 1940 to 1948 because of World War II.

By 1924, when the Olympics came to Paris for a second time, most of the traditions of the modern Olympics were in place.9 The 1981 classic Chariots of Fire dramatizes these Olympics, and demonstrates the ways in which these Games contain elements of both the early games and our modern games. One of the film’s protagonists, Harold Abrahams, is a talented university athlete who is scouted, trained, and coached. The other, Eric Liddell, is a Scottish minister and talented amateur who does well enough in local races to consider trying to make the British Olympic team.

In my favorite scene from the film, Liddell explains to his sister why - while he is committed to their missionary work - he also believes competing in the Olympics is a worthy pursuit.

“I believe God made me for a purpose,” he says, “but he also made me fast! And when I run, I feel his pleasure.”

Prejudice

While the Olympics began with high ideals, and at their best embody sportsmanship, cooperation, and excellence, their 130-year history has also been plagued with controversy, scandal, and tragedy. Hosting the Olympics is often ruinously expensive, and governments - feeling the pressure to present their countries as perfect - have bulldozed poor neighborhoods, abused workers, and prioritized visitor experiences over the needs of their own people.10

Many times throughout the century, the Olympics have served as a proxy for existing international conflicts - such as the high stakes Cold War competition between the US and the USSR, or the boycott of apartheid South Africa.

While numerous books and articles have been written about the problems with the Olympics, one games stands out for its symbolism of the Olympics at their best and their worst: the 1936 Olympics in Berlin.

When the International Olympics Committee awarded the games to Berlin in 1931, Germany was still a republic. Three years later, however, Hitler seized total control, leaving countries around the world questioning whether or not to boycott the games.

As the excellent 2016 documentary Olympic Pride, American Prejudice explains, Hitler and his propaganda department saw the games as an opportunity to advertise the virtues of the Nazi regime and promote their Aryan ideals.

When political and sports leaders - especially American Jews - argued that attending the games would be both unethical and dangerous, the current American Olympic Association president - Avery Brundage, a 1912 Olympian and known racist himself - visited Germany and returned with assurances that Nazi Germany didn’t seem discriminatory to him!

Black track star Jesse Owens, incidentally, was in favor of the U.S. team attending. In a letter to Brundage, he argued that he and his fellow athletes should not be denied the opportunity to compete while at the peak of their careers, but rather should be given the opportunity to disprove Hitler’s racist ideology through their victory.

Hitler’s regime, meanwhile, worked overtime to give Berlin a friendly facelift, temporarily removing all anti-Jewish signage and graffiti and instructing citizens to treat Olympians the same regardless of race or nationality.

Back in the United States, after a tense meeting, members of the American Olympic Association voted on whether to boycott the Berlin Olympics. With razor thin margins - 58 attend, 56 boycott - they decided they were in.

By the time the Olympic trials were complete, the 359-member American Olympic team included 18 Black athletes and two Jewish ones: track-and-field stars Marty Glickman and Sam Stoller. Included in those eighteen were Tidye Pickett and Louise Stokes, track-and-field athletes and the first Black women to ever be on the Olympic team. In 1932, they had both been part of the team chosen for the Los Angeles Olympics, then had unceremoniously lost their spots in favor of white alternates hours before their respective events.

Also on the 1936 team was Mack Robinson, the older brother of legendary baseball player Jackie Robinson, and - of course - Jesse Owens.

Ironically, the documentary points out, the Black athletes experienced better treatment at the Olympic Village than they had in the segregated United States. On the steamship journey from the US to Germany, the Black athletes weren’t allowed to watch movies in the ship’s movie theater with the white athletes; at the Olympic Village, they got their hair cut at barbershops, dined, and went to parties with people from around the world. The Black track-and-field athletes were particularly popular with young German women, and children hounded Olympic athletes from every country for their autographs.

During the games themselves, of course, Nazi Germany’s true colors were on full display. When Cornelius Johnson, a Black high jumper, won gold and the United States’s first medal of the games, Hitler disappeared from his box and refused to shake his hand. For the remainder of the games, Hitler refused to publicly congratulate any athlete rather than shake a Black athlete’s hand.

The Black athletes also faced discrimination from their own team. After two white boxers lost their respective matches, the coach unceremoniously sent Black boxers Joe Church and Howell King home without competing, claiming they were “homesick.” The day before the 4x100 m men’s relay, their coach pulled the two Jewish members of the team from the competition. Stoller later called the action the “most humiliating episode” of his life.

After qualifying in the hurdles semi-finals, Tidye Pickett caught and broke her foot on a hurdle and had to be rushed to the hospital. Watching in the stands, her distraught friend Louise Stokes vowed to win gold in her upcoming race in her honor. She never got a chance; minutes before she was set to run the women’s relay, her coach pulled Pickett in favor of a white athlete again.

The eighteen Black athletes won half of the American team’s 167 points, including eight gold medals.11 Jesse Owens in particular made international headlines for winning four gold medals - in the 100 m, 200 m, 4x100 m relay, and long jump - dramatically making a fool of Hitler and his white supremacist ideology.

While the American press loved Jesse Owens as a symbol for their propaganda, the United States did not care about him - or his other seventeen Black teammates - as people. “That’s the real tragedy,” says sports historian Dr. Daniel Durbin. “They came back to a country they had represented successfully, and the country turned its back on them, and closed its eyes, and wanted them to drift off and go away.”

American Olympic Committee president Brundage stripped Owens of his amateur status when he decided to go home after the games instead of going on a fundraising campaign throughout Europe, and he never competed in another Olympic games. Mack Robinson, who returned home with a silver medal, could only find work as a street sweeper. And, in a stunning parallel, when Owens returned to the United States, President Franklin D. Roosevelt refused to invite him to the White House.

He didn’t want white Southern voters - a key demographic for his re-election - to see him shake Jesse Owens’ hand.

Pride

One hundred years after Eric Liddell ran the 400 m race in Paris, the Games returned to the City of Light, showcasing a greater breadth and diversity than ever before.

For the first time in the history of the Games, there was gender parity between male and female athletes.

Sixty-seven of the United States’s 126 medals were won by women (and 26 of the 40 gold medals), including world record-setting swimming phenomenon Katie Ledecky (two gold medals, one silver, one bronze); bronze for my beloved Ilona Maher and the rest of the women’s rugby team; and three gold and one silver for Simone Biles, who is possibly the greatest gymnast of all time.

Long jumper Tara Davis-Woodhall set a world record and then went viral for running straight into the arms of her cheering husband Hunter Woodhall, a double amputee runner who will be competing in the Paralympics in two weeks.12

Two female athletes - Egyptian fencer Nada Hafez and Azerbaijani archer Yaylagul Ramazanova - won medals while pregnant. Beloved diver and gay advocate Tom Daley brought his kids to see him compete one last time, winning a silver medal at his fifth Olympics.13

American runner Nikki Hiltz became one of the first non-binary athletes to compete at the Olympics.14 Athletes from Albania, Cape Verde, Dominica, and Saint Lucia won their nations’ first ever medals.

The games, of course, featured their share of controversies. Most famously, Imane Khelif - a female boxer from Algeria - faced unsubstantiated transphobic attacks from high profile figures including J. K. Rowling and Elon Musk, despite being born a cisgender woman in a country in which it is illegal to be gay or trans.

The games also produced their share of memes, from the bizarre breakdancing of Australian “Raygun” to the absolute dominance of the pommel horse demonstrated by geeky American gymnast Stephen Nedoroscik. The comedic gold medal, for me, goes to Turkish marksman Yusuf Dikec, who casually won his team a silver medal in air pistol without the use of any specialized equipment, prompting hundreds of jokes that he must be a hitman or mercenary on vacation.15

My favorite story to come out of the games, however, is that of British rower Lola Anderson.

During the 2012 Olympics in London, Anderson - who was fourteen at the time - wrote in her diary, ““My name is Lola Anderson and I think it would be my biggest dream in life to go to the Olympics and represent Team GB in rowing and, if possible, win a gold medal.” A few minutes later, however, she ripped the note out of her journal in embarrassment and threw it away. “Teenage girls don’t necessarily have the most belief in ourselves and I got very embarrassed,” she remembers. “I kinda thought ‘That was a really cocky, arrogant thing to have written’.

Despite Anderson’s anxieties about putting her ambitions in writing, she spent the next several years training and succeeding as a rower. In 2019, after she won a world title in the under-23 sculls, her father - who now had terminal cancer - asked her to bring him his personal lock box.

He opened it to reveal that he had found his daughter’s note in the trash and saved it all those years, confident that she would achieve her dream.

Unfortunately, Anderson’s father died months later, but his daughter kept pushing towards her dream. On July 31 - along with the other three members of her team - Anderson won her gold medal.

“I was 14 at the time so why would I believe?,” she says. “Young girls struggle a bit to see themselves as strong, athletic individuals but that’s changing now. My dad saw it before I did. My potential would not have been unlocked without the girls I crossed the line with. He would be very proud today.”

Failure

The Olympics are a complex, flawed institution, marked by corruption and by selflessness, by bitter rivalries and by incredible examples of sportsmanship. They may not be a pure and untarnished example of humanity at its best, but they are a shining example of humanity at its most - its most athletic, its most nationalistic, its most image-obsessed, its most disciplined, and - occasionally - its most beautiful.

At the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, Great Britain’s Derek Redmond was a favorite to win the men’s 400 meter sprint. During the semi-finals, however, only a few seconds into the race, Redmond’s right hamstring snapped, and he collapsed to the ground in agony.

In a split second, Redmond’s Olympic dreams were dashed, his career changed forever.16

After a moment, Redmond slowly got to his feet and began to limp towards the finish line, his face distorted by pain. Suddenly, there was a commotion on the sidelines, and a middle-aged man in a t-shirt and baseball cap - Derek’s father, Jim Redmond - impatiently pushed his way past Olympic officials and rushed to his son’s side.

In the clip, you can see Jim brushing intervening officials off, insisting “he’s my son” as he supports the weeping Derek. Together, slowly but surely, they completed the race. Though Derek was officially disqualified for finishing the race with assistance, the two men received a standing ovation from all 65,000 spectators when they finally crossed the finish line.

"The important thing in life is not the triumph, but the fight;” Olympic founder de Coubertin said in a 1908 speech. “The essential thing is not to have won, but to have fought well."

When it comes to the Olympics, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

My favorite this year? Kayak cross, which is a full contact white-water rafting kayak sport in which participants start by flying off a ledge into the water and, at some point during the course, are required to do a full 360 turn underwater just because.

And reading fanfiction about their imaginary love story. I’m still bummed that they never got together.

You’ll note that all of these memories are from the Winter Olympics, which is very Canadian of me. It’s honestly only this year that I’ve really gotten into the Summer Olympics with equal enthusiasm.

The gold medal for best Opening Ceremonies outfits this year unquestionably goes to Mongolia, whose beautifully embroidered costumes went viral.

The USA has only missed one Olympic Games, the 1980 Moscow Games, and was the first non-European country to host. By contrast, the country with the next highest number of medals (2,011), Russia/the Soviet Union., did not compete from 1920 to 1952 and has been excluded from various games since then as well. Only three countries - France, Great Britain, and Switzerland - have a 100% participation rate.

Most of the material from this section comes from Margaret Timmers’s book A Century of Olympic Posters. This quote is from a January 31, 1911 letter to de Coubertin’s secretary Kristian Hellström.

As a limited edition book published 12 years ago in Britain, it will run you a pretty penny new, but I got it for free from my local library and you might be able to too!

The Winter Olympics began in 1924, and ran in the same year as the Summer Olympics until 1992.

With the notable exception of the torch relay from Athens, which first occurred at the Berlin Olympics in 1936. More on those Olympics in a moment.

In the same 99% Invisible episode, Avery Trufelman proposes something that I’ve been saying for years: the Olympics should permanently take place in Greece, boosting the Greek economy and saving other countries from the financial burden and political pressure of hosting.

Countries received five points for gold, three points for silver, and one point for bronze

In 1948, Sir Ludwig Guttman organized a competition between patients at several hospitals across the city to coincide with the 1948 London Games, as an effort to encourage the rehabilitation of wounded soldiers. In 1960, Guttman again sponsored a “parallel Olympics” in Rome, marking the official beginning of the Paralympic Games

Daley also went viral during the 2020 Tokyo Olympics for knitting in the stands, a habit he kept up this year. He knit an entire sweater, as well as gifting knitted medal covers to athletes including Ilona Maher

Hiltz, who uses they/them pronouns, competed in the women’s category, and came 7th in the 1500 m.

Much like the American college students who won shooting medals in the first Olympic games!

Two years after the Barcelona Olympics, Redmond’s surgeon told him he would never race again. He went on, however, to a successful career in professional basketball

I love the Olympics too, for many of the reasons you listed. It's a great opportunity to pay attention to sports and athletes that I would never engage with otherwise. Probably not surprising but I kept a spreadsheet of the time I spent watching - 20 different sports and about 22 hours of watch time over the two weeks!

Also, I have to recommend this Jon Bois video on the 1904 St Louis Olympic marathon, which has to be one of the most insane stories in sports. https://youtu.be/M4AhABManTw?si=i7lI4H8e_x5FaDkv

Great wealth of information. I'm looking forward to watching replays of many things I missed.