Song of the Week: “Wavin’ Flag,” by K’NAAN - “They’ll call me freedom, just like a wavin’ flag”1

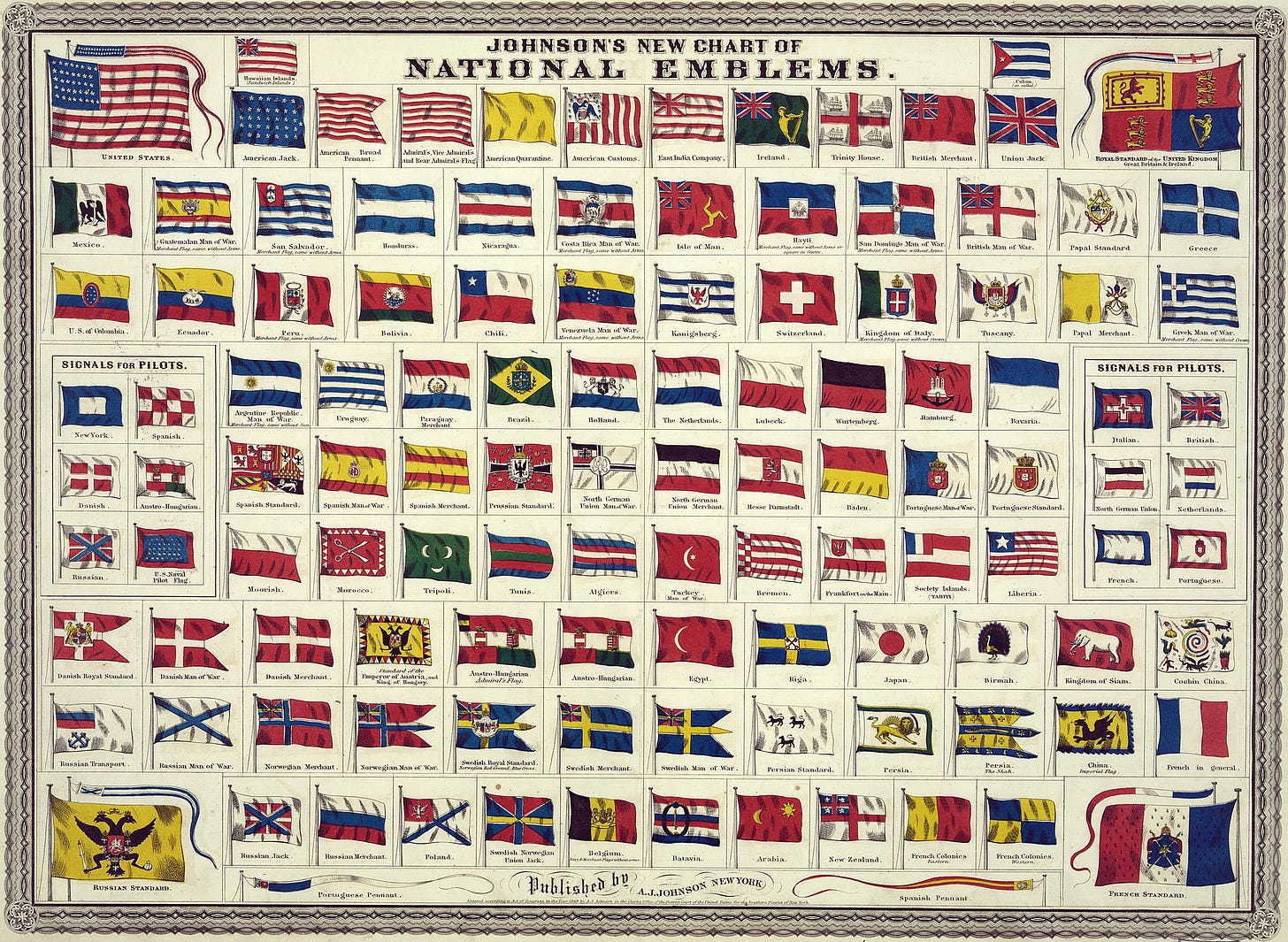

When I was a kid, one wall of our kitchen was covered by an enormous world map, bordered with the flags of every country. During meals, if we got bored, my parents would ask us questions about geography: some specific, some open-ended. “What’s the capital of Argentina? Can you find three countries that begin with B? Which country’s flag is only a single color?”2

The hours spent staring at that map gave my brother and I a great sense of international geography, which I’m very grateful for. It was also my first introduction to many countries’ flags, from the very simple (Poland)…

to the very complicated (Belize)…

to the very unusual (Nepal).

I spent the first half of this week in Michigan and the second half in Ontario, and thus was able to see both places decked out for the Fourth of July and Canada Day. The abundance of stars and stripes and maple leaves got me thinking about flags in a way I seldom have since those kitchen table days.

Flags tend to fade into the background, until suddenly they don’t: because they are lowered to half mast, or displayed as a political statement, or destroyed as a form of protest. They represent countries, states, cities, causes, and ideas. We display them in so many ways: flying outside of our government buildings, schools, and homes; as patches sewn on our backpacks or emojis in our Instagram bios; transformed into bikini tops, frisbees, and disposable napkins; tattooed on our bodies.

Flags often feel so powerful and sacred that we see them as timeless - but they aren’t, of course. There was a time before the Canadian maple leaf, before Old Glory, before national flags existed at all. How did we get from there to here?

Finding the answer to that question will require a bit of amateur vexillology: the study of flags.3

Stars and Stripes and Lions and Tigers and Bears, Oh My!

So, let’s say you’re designing a flag: because you’re starting something new, like when Nunavut became a Canadian territory in 1999.

Or to symbolize an important change, such as in 2021 when Mississippi opted to retire its flag incorporating the Confederate Battle Flag in favor of a new, less racist design.

How do you make sure your design is effective?

The first thing you might want to do is choose some colors that are symbolic for your people: they can be drawn from your landscape, or reference the symbol of a figure from your history, or simply reflect important virtues (red for blood, green for abundance, blue for the ocean, etc).

Whatever you do, however, make sure that you choose a vivid color that will contrast well against other colors: red, white, blue, yellow, green, and black are all popular choices. This interactive tool from Time can give you a helpful insight into every color used in a national flag, and allows you to sort the world’s flags by color.

You’ll likely also want to follow a few other principles that will help make your flag iconic, easily recognizable from a distance, and distinctive. YouTuber CGP Grey outlines these principles - and then ranks every U.S. state flag according to those principles - in this video:

Keep it simple - something a child could draw

Make it distinct at a distance

Three colors or fewer unless you really know what you’re doing

Symbols - have them. Your colors and what you design them with should mean something.

Words on a flag? The ideal number is 0. It’s a flag, not a note you’re passing in class.

A few months later, he followed up his state rankings with one of the Canadian provinces and territories.

How does your home’s flag measure up to his criteria? How might you redesign it?

Vexilloids!

Like many other widespread phenomena, flags do not originate in one place - many human societies seem to have simultaneously developed the concept of a representational symbol that can be reproduced and displayed prominently.

The earliest example of vexilloids - objects used representationally the way we would use a flag - is on the Ancient Egyptian Narmer Palette, a small sandstone object used for mixing makeup that dates from around 3000 BC.

The Palette, which scholars think may depict King Narmer uniting Upper and Lower Egypt, includes a small group of soldiers carrying long poles tipped with different decorative objects. While these are obviously not flags, they can give us some insight into flags’ original purpose: to be practical rallying points on battlefields, and to symbolize a leader’s dominance and might.

Other countries developed similar objects: ancient Roman units carried poles topped with their identifying symbols, such as eagles, sometimes with attached linen banners. The Chinese emperor Wu of Han’s first century tomb includes carvings of horsemen carrying banners. Tradition holds that Muhammad flew a plain black flag during his 7th century conquest, and extant coins from the 9th century AD suggest that Vikings frequently carried banners emblazoned with ravens.

Medieval trade with China led to the widespread availability of silk throughout Europe and Asia, giving us the fine, sturdy fabric frequently used for contemporary flags. Much of the symbolism we associate with flags also developed during the medieval period, due to the rise of heraldry.

In the 1100s, as styles of armor covered knights’ faces, they began to develop symbols that would be incorporated into their armor and shields, allowing for easy identification on the battlefield. Gradually, strict guidelines for heraldry emerged, with colors, shapes, and animals carrying specific meanings. You can read more about those guidelines in this beginner’s guide.

Heraldic symbols made their way not only onto shields and armour, but also into coats of arms, banners, and other decorative objects. During the Crusades, knights carried their heraldic banners into battle, and in medieval tournaments, they employed them as well. For most nobles, their heraldic symbols were passed down to their children and became symbols of their dynasties; the exception to this was generally monarchs, who created new symbols to differentiate their reigns from those of their predecessors.

You can see examples of these heraldic banners in this 16th century illustration of the banners of the Knights of the Order of the Garter, the most prestigious chivalric order in Great Britain.

Though often simplified, heraldic symbolism endures today, in coats of arms for countries, states, and universities, and - of course - in many flags.

A few of our modern flags, in fact, were created during this period. The oldest continuously used flag in the world is from Denmark: the ‘Dannebrog.’ We have examples of it being used in the fourteenth century, and it was officially adopted in 1625, by King Christian IV, making it 389 years old.4

Another flag with medieval origins is the ever-familiar Union Jack: though it was adopted in 1801, it combines three existing heraldic symbols representing the patron saints of England, Scotland, and North Ireland: the red St. George’s Cross, the diagonal white cross of St. Andrew, and the diagonal red cross of St. Patrick.5

Our Flag Means Death

Many flags that we today associate with countries as a whole began as the official symbols for countries’ navies: that’s the case for the Dannebrog, as well as the original 17th century Union Jack, which combined the flags of England and Scotland.

During the “Age of Sail,” which lasted from the 15th century to the mid 19th century, navies became essential to countries’ trade and military strategy. Because captains needed to quickly identify whether ships at a distance were friend or foe, most countries adopted naval flags that could be clearly distinguished through a spyglass.

Today, however, we most associate the Age of Sail with a different set of flags: pirate flags.

While we usually picture a white skull and crossbones on a black background, pirates used a variety of flags, many of which were associated with individual pirate captains (much like the knights and rulers who came before them).

The main purpose of these flags was to terrorize their potential victims, encouraging them to surrender without many casualties for the pirate crew. They were so frightening in part because, unlike nation-sanctioned privateers, pirates were not held to any legal codes, and thus did not have to spare the lives of sailors who surrendered following a naval battle.

As Peter Leeson writes in Pirational Choices: The Economics of Infamous Pirate Practices, “To achieve their goal of taking prizes without a costly fight, it was therefore important for pirates to distinguish themselves from these other ships also taking prizes on the seas” (10). The pirate flag became such a symbol of horror, by the way, that merely possessing one was considered an admission of guilt, punishable by execution.

As Taika Waititi’s goofy pirate comedy Our Flag Means Death demonstrates in its opening scene, however, getting to a point where your pirate flag strikes fear in the hearts of all those who see it is not that straightforward.6 When the foppish pirate captain Stede Bonnet assigns his crew a flag-sewing competition, the best they can come up with is a cat. “Cats are terrifying,” says crew member Frenchie. “Everyone knows that. ‘Cause they’re witches. And they’ve got knives on their feet.”

Sometimes, unfortunately, flags just don’t have their intended effects.

Empire Building

Even as pirates were using flags to demonstrate their statelessness, other countries were using them to establish new identities. With the American and French Revolutions at the end of the eighteenth century, national leaders were faced with an ideological challenge: how do you shift citizens’ allegiance from a monarch to the idea of the country itself?

In the late 1770s, the American army - still in the midst of the American Revolution - began fighting under a flag featuring thirteen red and white stripes, for the thirteen founding colonies, and thirteen white stars on a blue background, for the states those colonies became. The flag’s brilliance lay in its focus - on entire states, rather than leaders or saints - and in its adaptability. As states were added to the Union over the next two centuries, stars were added to the flag, until Hawaii became the fiftieth state on July 4, 1960, and the flag took the form that it still bears today.

The American flag became particularly vital to collective identity during the American Civil War, when the Confederacy seceded from the Union and established their own vexillological identity, most vividly remembered today through the Confederate Battle Flag. One of my favorite artifacts from the Civil War is Union General Sherman’s 23rd Corps’ battle flag: an American flag sewn from pieces of captured Confederate flags.

Following the end of the Civil War, the Confederate Battle Flag was not widely flown until the twentieth century, when it was adopted by Confederate sympathizing groups like Sons of Confederate Veterans and Daughters of the Confederacy. In 1948 the Dixiecrats officially adopted it as a symbol of their opposition to desegregation. As historian John Coski writes, the Dixiecrats shared the Confederacy’s opposition to potential changes in “the South’s racial status quo. There could be no more fitting opposition than the Confederate battle flag. Although segregationists lost their battle and their cause was discredited, attitudes of white supremacy live on.” (294)

During the Civil Rights struggles of the 1950s and 1960s, Southerners frequently adopted the Confederate flag as symbols of their opposition to integration, and it endured in official symbols of many southern states until the twenty-first century.

At the same time that Americans were fighting over the future of their nation - and its flag - the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw a similar movement towards nationalism in Europe: one that was closely associated with colonization and empire.

The flags of Belgium, the Netherlands, Spain, France, and England flew in colonized countries around the world, symbolizing control, exploitation, and violence. When colonized countries demanded their freedom, having their own flags was an important step in declaring independence.

A vivid example of this comes from the Indonesian struggle for independence, which took place in the years surrounding WWII. Indonesia was colonized by the Netherlands in the 17th century, and known as the Dutch East Indies until it was occupied by the Japanese during WWII. The rising Indonesian independence movement adopted a simple red and white flag, based on the colors of the eleventh century Mahajapit Empire.

After three years of Japanese occupation, control of Indonesia returned to the Netherlands, and the Dutch flag was flown again in important buildings. According to local legend, in September 1945, protestors snuck into the Hotel Oranje - a fancy hotel associated with Europeans - and ripped the blue bar from the bottom of the Dutch flag, transforming it into the new Indonesian flag. Following the protest - and the ensuing war for Indonesian sovereignty - the hotel was renamed the Hotel Merdeka: Independence Hotel.

These examples all speak to the enormous power that flags hold: as symbols of independence and domination, patriotism and protest.

Countries work hard to make their flags feel like sacred objects, and many discourage or even outlaw destroying them because of the symbolic implications.

To many Americans, burning the American Flag is a heinous act. Contrary to popular belief, however, it is actually not currently illegal. In 1968, in response to Vietnam War protests, Congress passed the the Flag Protection Act, making it illegal to publicly destroy an American flag. In 1990, however, the Supreme Court struck down the Act, ruling that citizens’ First Amendment rights to free speech were more important - a greater testament, perhaps, to American freedom than any flag.

In “A New National Anthem,” Ada Límon, the current Poet Laureate of the United States, captures the complexity of how many of us feel about the American flag, and all it stands for:

The truth is, I’ve never cared for the National Anthem. If you think about it, it’s not a good song. Too high for most of us with “the rockets red glare” and then there are the bombs. (Always, always, there is war and bombs.) Once, I sang it at homecoming and threw even the tenacious high school band off key. But the song didn’t mean anything, just a call to the field, something to get through before the pummeling of youth. And what of the stanzas we never sing, the third that mentions “no refuge could save the hireling and the slave”? Perhaps, the truth is, every song of this country has an unsung third stanza, something brutal snaking underneath us as we blindly sing the high notes with a beer sloshing in the stands hoping our team wins. Don’t get me wrong, I do like the flag, how it undulates in the wind like water, elemental, and best when it’s humbled, brought to its knees, clung to by someone who has lost everything, when it’s not a weapon, when it flickers, when it folds up so perfectly you can keep it until it’s needed, until you can love it again, until the song in your mouth feels like sustenance, a song where the notes are sung by even the ageless woods, the short-grass plains, the Red River Gorge, the fistful of land left unpoisoned, that song that’s our birthright, that’s sung in silence when it’s too hard to go on, that sounds like someone’s rough fingers weaving into another’s, that sounds like a match being lit in an endless cave, the song that says my bones are your bones, and your bones are my bones, and isn’t that enough?

Pride

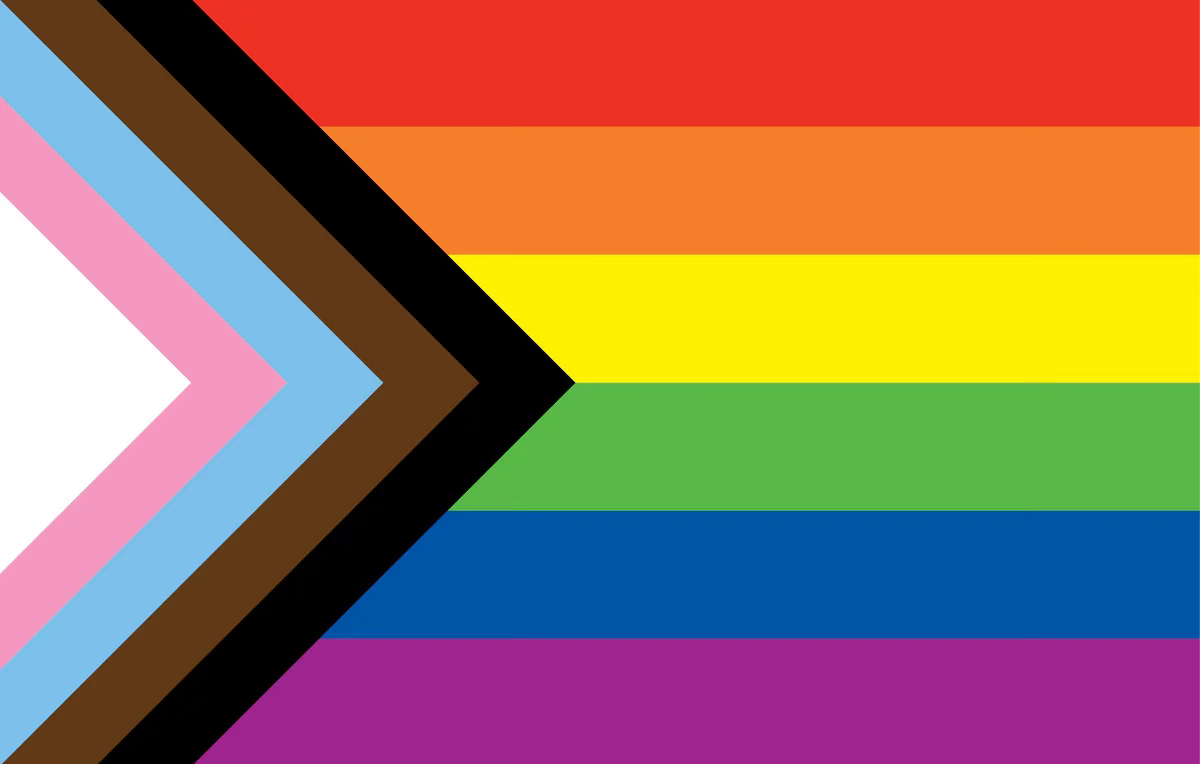

One of the most iconic flags of the last hundred years, however, is not a national flag at all: the rainbow-striped Pride Flag.

In 1978, Harvey Milk - a gay activist and the first openly gay man elected to public office in California - asked the artist Gilbert Baker to design a flag representing gay pride. Baker created an eight-striped rainbow flag, with each stripe representing a different value of the queer community: as the Human Rights Campaign explains, “hot pink represents sex, red symbolizes life, orange stands for healing, yellow equals sunlight, green stands for nature, turquoise symbolizes magic and art, indigo represents serenity, while violet symbolizes the spirit of LGBTQ+ people.”

In November of 1978, Harvey Milk was assassinated, and in the wake of his death there was widespread demand for the rainbow flag as a show of support. Due to manufacturing difficulties, the pink stripe was omitted from the new widely-produced flag, and Baker decided to eliminate the turquoise stripe as well as a design choice. The final result was the familiar six-stripe rainbow flag that has remained a symbol of the queer and trans community ever since.

Despite the ubiquity and widespread use of the six-stripe rainbow flag, the last forty years have seen the emergence of more and more specific pride flags. Some, like the now widely-recognized trans pride flag, have specific origin stories: it was created by Monica Helms in 2000. Others, such as the pink, yellow, and blue pansexual flag, are murkier: it seems to have emerged on the blogging website Tumblr in 2010, and was eventually adopted more widely.

In June 2018, artist Daniel Quasar released a redesigned Pride flag, the “Progress Pride Flag” which features a triangle with black and brown stripes representing the intersectional oppression of queer people of color, as well as the white, pink, and blue stripes of the trans flag, to draw attention to the particular persecution and alienation trans people face.

Many individuals and institutions have adopted this flag as a more inclusive pride flag. Others have pushed back, either for ideological reasons (they argue that the original rainbow flag already explicitly includes everyone) or for aesthetic ones (they think the new flag is over-complicated and ugly).

A visit to any Pride festival or market these days will reveal a panoply of different pride flags for sale, of varying levels of obscurity, along with stickers, pins, and other objects emblazoned with their component colors.

It’s enough to make you believe that someone out there has a sinister agenda - and by “someone,” I mean flag manufacturers.

At the same time, displaying the rainbow flag still has political implications, even as public support for LGBTQ+ people has dramatically increased. Last year at the University of Waterloo, a student ripped up a small Pride flag, entered a gender studies classroom and attacked the teacher and students with a knife.7

In the following year, homophobia and transphobia on campus have persisted.

Like many other staff and faculty members, I display a small pride flag on the bulletin board outside my office door to indicate my support for LGBTQ+ students. Though these flags are stickers, many of us used to simply pin them to our bulletin boards or tuck them into the corner of our white boards so that we wouldn’t potentially damage university property. One morning a couple months ago, however, we came in and discovered that someone had stolen every pride flag that hadn’t been stuck down, and attempted to scrape off the ones that were.

This petty vandalism was just as symbolic as the flags it removed, designed to make queer students and staff feel unwelcome and unsafe.

It didn’t stop us, though: I got a new pride flag sticker and stuck that one more permanently to my white board, adding a bisexual pride flag later for good measure. These are the flags that mean freedom to me, and I’ll do what I can to defend them.

When it comes to flags, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

Somali-Canadian rapper K’NAAN’s family emigrated to North America following the death of three of his pre-teen friends during the Somali Civil War. The first version of “Wavin’ Flag,” which I’ve included here, is from his 2009 album Troubadour. That original version of the song includes multiple lyrical references to diaspora, violence, and the refugee experience, including “So many wars, settlin' scores /Bringin' us promises, leavin' us poor,” and “we strugglin', fighting to eat / and wondering’ when we’ll be free.”

The song became very popular in Canada, reaching number two on the charts. It was then chosen by Coca-Cola as one of their official songs for the 2010 World Cup, which was held in South Africa (the first World Cup ever held in Africa). K’NAAN recorded the new “Coca Cola Celebration” mix, with lyrics rewritten to celebrate football and music incorporating the Coca Cola jingle. This is the version that charted around the world and was re-recorded in several languages.

For my entire childhood, Libya had a plain green flag. I only found out this week that, in 2011, they switched back the more complicated red, green, and black flag that Qaddafi had replaced in 1949.

I am indebted this week to the members of r/vexillology, which is a very fun subreddit to waste a few hours on

The white flag of surrender, parley, or peace-making, however, is older than any one country’s flag, dating back to the thirteenth century. There is evidence that white flags or banners were used for this purpose as well in India and Portugal. The use of the white flag as a protected request for parley is included in Chapter III, Article 32 of the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907

Poor Wales doesn’t get representation in the Union Jack because it had already been incorporated into the British empire prior to the creation of the first Union Jack flag. I really feel like the Welsh dragon would add a certain je ne sais quoi, though, don’t you?

There have been several high-profile cases in the last few years of people being prosecuted for hate crimes after defacing or destroying pride flags, raising interesting questions about free speech. Law professor Mark Walters explores them here. Homophobic and transphobic sentiment has endured on campus in the year that followed.