Song of the Week: “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” by Gordon Lightfoot - “The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down”

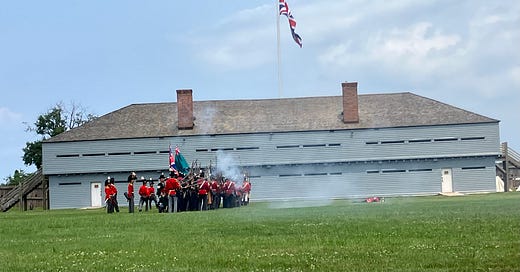

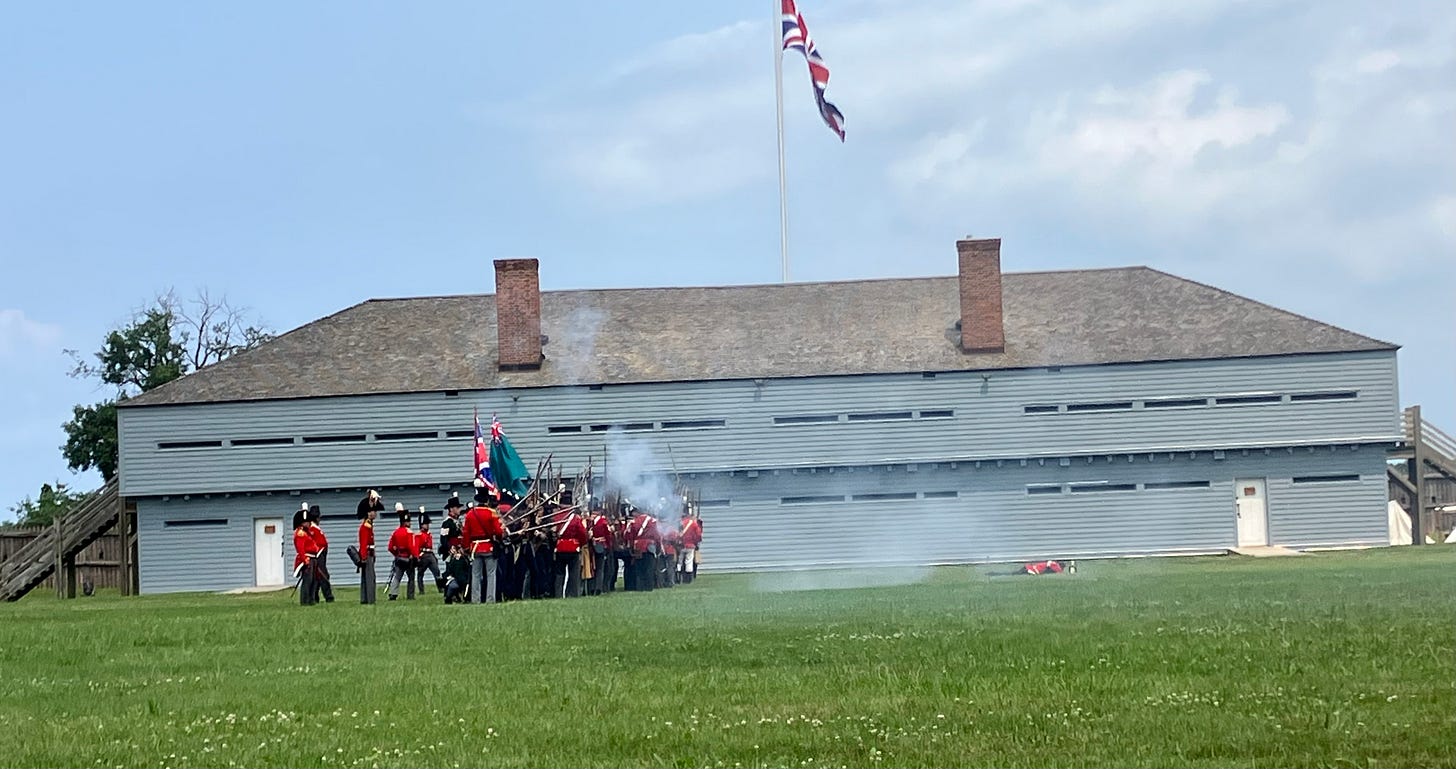

While I loved Disney World, arcade games, and going to the zoo as much as the next kid, my favorite tourist destination when I was little was Fort George, a historical site in the Niagara Falls region that was of pivotal importance during the War of 1812. After piling into the car and driving down beautiful roads lined with lush grape vines and fruit trees, we’d spend the afternoon watching musket firing demonstrations, chatting with a working blacksmith, and sampling cookies that had been baked in an enormous stone fireplace.1

I loved everything about visiting the fort: playing with wooden toys and rag dolls in the barracks where married soldiers lived with their families, examining real musket balls and shards of china found in archaeological digs, climbing to the top of the lookout tower and peering at the American Fort Niagara barely visible across the river. The best visits were on reenactment weekends, when dozens of volunteers would camp in canvas tents outside the fort, wearing cotton dresses and bonnets, selling historical reproduction wares.

In summer 2023, I finally got to take Taylor to Fort George for the first time, which happened to be on a weekend that they were reenacting a major battle from the War of 1812. We watched from the sidelines as the armies marched within only a few feet of each other and then fired their muskets in unison. “I’m never going to picture battles from that era the same way again,” Taylor told me afterwards. “They really could see the whites of each other’s eyes!”

Fort George is what’s known as a “living history” museum, a historical site in which costumed volunteers or employees teach visitors about a particular time and/or place in history, usually while also performing daily tasks using authentic methods. Growing up, living history museums were a major focus of our family vacations. I bought paper dolls and a cherished parasol at Colonial Williamsburg, learned I needed glasses thanks to an eye chart on a battleship, and, on one memorable occasion at St. Marie-Among-the-Hurons, I watched a surgeon talk through the process of a leg amputation without anesthesia, and was so nauseated by the vividness of his descriptions that I ended up retching in the canal.

These frequent visits to living history sites are, I’m sure, part of why my brother Paul became an archaeologist. For me - a frequent reader of historical fiction - they were chances to step into another world. The events I encountered in books like the Magic Tree House and Dear Canada became so much realer to me when I could smell the woodsmoke, touch the tar-covered ropes, hear the boom of the cannons.

Building a National Identity

The Fort George I visited as a child is not, in fact, the original fort: with the exception of the powder magazine - which has eight foot thick stone walls and a metal roof - the entire fort and all of its buildings are reconstructions built in the late 1930s.2

The original fort was built by the colonial British administrators in the 1790s, and many of the buildings were destroyed during the 1813 battle that Taylor and I watched volunteers reenact 210 years later. After seven months of American occupation, it was recaptured by the British, and after the end of the war the grounds fell into disrepair.

During the 1890s, increasing patriotic sentiment in the recently created Dominion of Canada led to an interest in commemorating and preserving sites of national importance, and in 1919 the Advisory Board for Historic Site Preservation was created, with a focus on “great men,” the fur trade, and important battles. The site of the former Fort George was named a National Historic Site in 1921, one of 285 such sites that would be designated by 1943. Of those sites, 105 were related to military history; 52 were related to the fur trade; and 43 were related to famous historical figures (almost all of them white men). The choice of commemorations was also heavily biased towards Ontario, specifically sites that were relevant to the War of 1812.

For my American readers, this particular focus on the War of 1812 might seem odd. For many Americans, the War of 1812 is a footnote; for Canadians, it is a defining moment in the establishment of Canadian identity, despite the fact it predates the founding of Canada as an independent country by more than fifty years.

The prominence of the War of 1812 in these early historical sites can largely be attributed to the fact that the Advisory Board for Historic Site Preservation’s first chairman, Brigadier General Ernest Alexander Cruikshank, was an expert on the War of 1812. As historian C.J. Taylor notes in Negotiating the Past: The Making of Canada’s National Historic Parks and Sites (1990), that focus also served a political purpose: to reinforce national affinity with the British empire and commemorate resistance to so-called “Americanism” (6). In much the same way that Canadian soldiers fought off American invaders more than a hundred years earlier, these sites suggested, modern Canadians persisted in having their own unique culture and achievements despite enormous pressure from the south.3

When Fort George reopened as a historical site in 1940 - and even more so when it became a living history site in 1969 - it became a crucial site in telling the story of the War of 1812, and establishing that uniquely Canadian identity. It’s part of why I wrote a paper on the Battle of Fort Detroit - an immensely embarrassing loss for the American army - during an American history class I took while attending university in the United States. It’s why, to this day, despite otherwise being deeply uncomfortable with nationalism and empire, I’ll gleefully sing along to the Arrogant Worms song “The War of 1812,” which celebrates burning down the White House.

“You Can’t Change History”

When the Advisory Board for Historic Site Preservation began commemorating historical sites, they were doing something called “public history”: a term coined in the 1970s to describe a wide variety of activities, sites, and pieces of media created to communicate history to people who are not themselves trained historians. Textbooks, academic articles, and books are generally not considered public history, but pretty much everything else can be considered fair game.

There is also spirited disagreement over what counts as public history, and who gets to do it: The Oxford Handbook of Public History (2017), for example, limits their definition to trained historians doing educational work, including “consultants, historians in the government, museum curators, national parks staff and heritage interpreters, local community historians, historical filmmakers, and digital historians” (3). Others argue that any time people are telling stories that make truth claims about the past that are meant to be consumed by a general audience, they are doing public history.

Public history includes, of course, vivid and dynamic interpretive sites like Colonial Williamsburg or Fort George. It also includes more traditional museums, like the wonderful Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto, which illustrates world history through changing footwear, or the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., which gives each visitor a booklet about one of 600 different real people, to carry with them as they travel through the museum.

But public history also exists outside of educational sites that you might visit on a field trip or family vacation. It includes the ubiquitous plaques and markers that you’ll find in tiny towns and big cities, put up by governments or local historical societies. Taylor just finished a work trip that took him through Ohio; as he passed astronaut Neil Armstrong’s hometown of Wapakoneta, every highway exit included the phrase “first on the moon.”

When people participate in the Society for Creative Anachronism] or attend war reenactments, they are doing public history. The excellent self-guided tour of Boston historical sites that Taylor and I took via the National Parks app was public history, as was the absurd leadership training my friend’s company made her do while visiting Gettysburg.

One can even argue that movies like Braveheart (1995) and Pirates of the Caribbean (2003) are a form of public history, albeit ones that take enormous liberties with their source material.

And then, of course, there are the statues.

Here’s the thing about public history: it is often just as much - or more - about shaping how members of the public see themselves and their communities as it is about providing an accurate and objective accounting of the known facts (if such a thing is even possible).

In 2017, following the violent Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Va, people across the United States started calling for the removal of statues honoring the Confederacy. More than thirty cities removed statues and monuments, including cities like Los Angeles, California and Helena, Montana that had nothing to do with the Civil War.

During this push for removal, President Trump tweeted: “Sad to see the history and culture of our great country being ripped apart with the removal of our beautiful statues and monuments. You can’t change history, but you can learn from it. Robert E Lee, Stonewall Jackson - who’s next, Washington, Jefferson?”

Similarly, Carl V. Jones, a leader of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, denounced “the hatred being leveled against our glorious ancestors by radical leftists who seek to erase our history.”

In their statements, Trump and Jones clearly identify these statues as artifacts vital to accurately and honestly commemorating the history of the United States. But here’s the thing: these Confederate memorials don’t even date back to the Civil War. Instead, the vast majority of the Confederate statues and memorials in the United States were erected during the early 1900s or during the 1950s and 1960s - times of major pushes for civil rights and racial equality, and immense racist backlash.

As James Grossman, executive director of the American Historical Association, told NPR, “These statues were meant to create legitimate garb for white supremacy. Why would you put a statue of Robert E. Lee or Stonewall Jackson in 1948 in Baltimore?” Similarly, history professor Jane Dailey argues that the statues were erected as a kind of rhetorical terrorism, meant to reenforce the enduring dominance and power of white people. “Most of the people who were involved in erecting the monuments were not necessarily erecting a monument to the past,” Dailey says, “but were rather erecting them toward a white supremacist future.”

How We See Ourselves

The best book I have read about public history - one of the best non-fiction books I’ve ever read, period - is Clint Smith’s How the Word is Passed (2021).

Smith - a journalist, educator, and poet - visits sites throughout the United States (and one in Angola) and analyzes the way they present the history of slavery. He chats with visitors, tour guides, and historians to understand how they think about American history, and how their narratives of history affect their understanding of their own identities. From a plantation-turned-maximum security prison where the majority-Black prisoners pick cotton in the fields, to a Memorial Day celebration where Confederate sympathizers claim they are interested in “truth, not mythology,” (170), Smith examines the many often contradictory ways that Americans grapple with one of their country’s most horrific legacies.

In the book’s opening chapter, “‘There’s a difference between history and nostalgia’: Monticello Plantation,” Smith visits the palatial plantation home of Founding Father Thomas Jefferson, and examines Jefferson’s connection to slavery. Jefferson, who wrote so eloquently about the equality and liberty of all men, owned, tortured, bought and sold human beings throughout his life. At any given time, Smith notes, there were around 130 enslaved people living and working at Monticello; the most famous of those was Sally Hemings. Hemings was likely the enslaved half-sister of Jefferson’s wife Martha; Jefferson began raping her when he was in his forties and she was sixteen, resulting in at least six children.

In the first tour Smith takes, his guide is an older white man named David who came to work at Monticello after more than thirty years serving in the U.S. Navy. The tour, which focuses on Jefferson’s relationship to slavery, is optional; around 80,000 of Monticello’s 400,000 annual visitors choose to take it.

Using oral histories from the descendents of enslaved people, archaeological evidence, and excerpts from Jefferson’s own letters and records, David paints an unflinching and unsentimental picture of the ways in which the Founding Father justified the dissonance between his beliefs about liberty and his treatment of human beings. David also insists on humanizing the enslaved people who lived at Monticello, describing the games the children played on Sunday afternoons, the songs people sang as they worked, and the rituals they used to commemorate births, weddings, and funerals.

This rigorous reckoning with the history of slavery at Monticello - one that began in the 1990s - has replaced the more nostalgic and entertaining ways in which Jefferson’s story used to be told. For the first thirty years that Monticello was open as a historical site - from 1923 until the 1950s - tours were conducted by Black guides dressed in the livery of enslaved people. Some of them were direct descendents of the actual people Jefferson enslaved. The picture they painted of life at Monticello was an idealized, Gone with the Wind-esque story of happy slaves and a benevolent master.

After David’s tour, Smith approaches two white women, Donna and Grace, who are visiting Monticello as part of a vacation they’re taking together.

I asked them if, before coming on this tour, they had been aware of Jefferson’s relationship to slavery, how he had flogged his enslaved workers, how he had separated loved ones, how he had kept generations of families in bondage. Their answers were swift and sincere.

‘No.’

‘No.’

They both shook their heads, as if still perplexed by what they had just learned. There was a discernible sense of disappointment, perhaps in themselves, perhaps in Jefferson, perhaps in both.

‘You grow up and it’s basic American history from fourth grade…He’s a great man, and he did all this,’ Donna said, gesticulating with her hands and almost retroactively mocking the things she had previously been taught about Jefferson. ‘And granted he achieved things. But we were just saying, “this really took the shine off the guy.”’ (20)

Not all visitors to Monticello, unfortunately, are so receptive to learning about Jefferson’s role as an enslaver - especially when their tour guide is a young white woman, or a person of color. 4 And - while many guests are shocked or taken aback - some complain that the guides are focusing too much on slavery, or attempting to tear down Jefferson and America.

As David tells Smith, “when you challenge people, specifically white people’s conception of Jefferson, you’re in fact challenging their conception of themselves” (41).

Narrators

In an era where childhood education focuses obsessively on STEM (or at best, a begrudging STEAM), and less than 1.2 percent of university students are history majors, public history plays a central role in educating people about the context in which they live their lives.5

Of course, there is no such thing as history without perspective - in constructing a narrative everyone chooses which things bear mentioning and which will be left out, which people are main characters and which ones are footnotes at best. As Haitian scholar Michel-Rolph Trouillot writes, “The inability to step outside of history in order to write or rewrite it applies to all actors and narrators” (140). That is why, when we are doing the work of public history, it is so important to include more than one memory, more than one kind of voice.

In 2017, to celebrate Canada’s 150th birthday, Parks Canada announced that free passes to all of the nation’s national parks would be available to anyone who wanted them. In my enthusiasm, I requested four, only realizing after the fact that only one was needed per family.6

That year, my family visited several historical sites and parks around Ontario. We also, of course, visited Fort George. Though much of our visit was familiar - same smells of baking in the kitchens, same musket demonstrations, same paper dolls in the gift shop - one thing had notably changed: there was a much larger and more thoughtful exhibit about the role Indigenous people had played in the War of 1812 and the history of the fort, centering the voices of those people and their descendents.

Though the project of public history is an inherently fraught one, the stories told about Canada’s national identity today are far more diverse - and far more complex - than those told by the Advisory Board for Historic Site Preservation a century ago. In 2020 and 2021, four residential schools - places where Indigenous children were torn from their parents, sexually and physically abused, and stripped of their cultural traditions, all at the command of the government - were designated as National Historic Sites.

This recognition, says Chief Dennis Meeches of the Long Plain First Nation, was the result of “many years of hard work” that saw “survivors and community members [join] in the effort to preserve the building and their stories, because this is also a story of resilience and a long journey towards healing.”

As we face a second administration by a white supremacist aspiring dictator who calls Confederate statues a beautiful part of history but condemns teaching about slavery in schools as “toxic propaganda” and “ideological poison,” public history matters more than ever.

What lies do we whitewash into unassailable truths? Whose suffering and dreams do we decide is worthy of commemoration? If we do not reckon with the ugly parts of our collective histories, will we be doomed to repeat them?

When it comes to public history, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

And, on one notable occasion when I was 14 or so, I spent over an hour watching a very cute baker make cookies while asking him every question I could think of.

Fort George was recreated as part of a larger collection of public works projects meant to create jobs during the Great Depression. Similar efforts and restorations took place in the United States during this same period.

The asymmetry of how Canadians and Americans see each other is a source of consistent amusement (and occasional embarrassment) for me. Generally, Americans think of Canadians fondly, and Canadians see Americans with a mixture of hostility, envy, and fondness usually reserved for a boorish older brother. This was vividly demonstrated during a series of interactions I saw on Twitter in 2018 where folks discovered that American cheered for Canadians second after the USA during the Winter Olympics. Canadians, by contrast, tended to cheer for Canadians first, whoever was up against Americans second, then all other Commonwealth countries, all other countries, the United States, and then finally Russia. You can see similarly asymmetrical sentiments in this Reddit thread from last summer’s Olympics.

Though Monticello’s director of African American history, Niya Bates, is a Black woman, very few tour guides are Black. At the time of Smith’s visit in 2017, only four of the site’s eighty-four tour guides were Black. This, notes manager of historic interpretation Brandon Dillard,, is partly because of how psychologically exhausting the job can be for Black guides: “people say some pretty insensitive and unbelievable things” (39).

STEM refers to Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math. The sometimes-added A refers to Art.

Don’t worry, I gave the others away to extended family and friends.

Fascinating in-depth overview of the importance of public history. Some day I hope to tour Monticello.

I had an argument with an American friend way back about the War of 1812. He insisted that it was a tie, because no land was won or lost. I insisted that Canada won, because we were attacked first and kept our land from being taken. I don't think I convinced him :p

I went to Monticello as a young teen. I don't know what version of the tour we did, but I remember them talking about how Jefferson freed a bunch of his slaves in his will. I remember having the thought, "but they still had to be a slave his whole life," and "but only some of them were freed?"