Song of the Week: “Reynadine,” by the Carolina Chocolate Drops1 - “If by chance you look for me, I fear you’ll not me find / I’ll be in my castle, inquire for Reynadine”

Content warning: today’s newsletter includes a photograph of an item featuring swastikas.

One of my all-time favorite comfort movies is A Knight’s Tale. Very, very loosely based on Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, A Knight’s Tale follows William, a peasant-born squire (played by a dreamy young Heath Ledger) as he poses as a noble-born knight and then struggles to maintain the facade while achieving wild success in a series of jousts.2

When it first came out, however, A Knight’s Tale was famously divisive among critics due to its musical choices: it opens with a crowd of medieval peasants at one of those tournaments singing Queen’s “We Will Rock You” and doing The Wave.

As director Brian Helgeland recalls in a 2021 article for Vulture, he wanted to make a movie about what tournaments would have felt like for people in the medieval period, rather than making any attempt at historical accuracy. “He argued that using a traditional orchestral score with violins was just as anachronistic as electric guitars, since violins hadn’t been invented in the 1300s yet either,” Ashley Spencer writes. “Plus, stadium sports like jousting required stadium music. And whether set in the 1370s or the 1970s, he says, ‘the ‘70s are always the ‘70s.”

My favorite example of how A Knight’s Tale blends the 1370s and 1970s is this scene, which takes place when William must attend a banquet for the first time after winning a tournament.

What begins as a series of stately movements set to strings and woodwinds slowly transforms into David Bowie’s “Golden Years,” until every dancer in the room is grooving along.

It’s tremendously fun, but more than that, it makes these characters feel vibrant and real despite living seven hundred years ago.

I’m intrigued by pieces of media like A Knight’s Tale, Marie Antoinette, and Bridgerton that intentionally incorporate anachronisms to communicate how people alive at different points in history may have experienced their worlds. I think it demonstrates our enduring fascination with the everyday life of our distant ancestors, and a desire to understand how they felt.

That same desire, I think, is why so many people attend Renaissance Faires. I have always loved dressing up and learning about history, so when a friend’s parents invited us along to Wisconsin’s enormous Bristol Renaissance Faire my junior year of university, I lept at the chance. I laced up my borrowed bodice, braided a crown into my hair, and dove headfirst into a day of browsing for handmade leather goods, eating fried food, and - yes - even watching a joust.

Days of Olde

But first, of course, the necessary definition:

What exactly is a Renaissance Faire? I’m sure by this point most of my readers have picked up some sense of the Renaissance Faire as a concept simply by cultural osmosis, regardless of whether or not you have attended one yourself.

Generally, they involve turkey legs and flagons of ale, knights in armor and ample bosoms, folk music and jousts, and vendors selling everything from forged iron to cheap trinkets originally purchased on AliExpress. While some Renaissance Faires claim to be set in a specific year, and may feature actors playing characters like Queen Elizabeth I, most events will feature performers and vendors representing a wide variety of eras, from the Anglo-Saxons to 18th century pirates.

That’s not even counting the wide variety of costumes worn by visitors, officially called “playtrons”: witches, fairies, cosplays from Game of Thrones and Lord of the Rings, steampunk apparel, and even groups of Star Trek officers.3

The delightful absurdity of Renaissance Faires is demonstrated by this scene from Rainbow Rowell’s Wayward Son, in which a group of actually magic British wizards stumble upon a Renaissance Faire in Nebraska.

As they see visitors dressed as fairies, Vikings, and Frodo Baggins, the narrator, Baz, become increasingly confused:

A horse, carrying a woman dressed as Elizabeth I, trots by. ‘Pardon me, chap.’ Another woman, dressed as Sherlock, pushes past us.’ Bunce waves her turkey leg at the whole preposterous scene. ‘Is the theme British?’ she asks, suddenly indignant. ‘Is it just weird and British?’ (101).

The average Ren Faire today can be described as equal parts historical re-enactment, live-action role play (LARP), theme park, and flea market. Some are massive, semi-permanent affairs, with their own devoted grounds and buildings, running every weekend all summer. The Bristol Renaissance Faire I attended in university falls into that category, as does the Colorado Renaissance Festival, which Taylor and I went to together in 2021.

Others are smaller events, run mostly by volunteers and held for a single day or weekend on fairgrounds or in a park. For the last two years, we’ve celebrated my best friend Jillian’s birthday by attending Robin in the Hood, which happens in the nearby small town of Elmira on the first weekend of June. They don’t have a castle or horses, but they do have a free archery range, blacksmithing demonstrations, and an impressive collection of local vendors including beekeepers, potters, and a couple who make beautiful museum replicas.4

Our local festival actually has a lot in common with the first Renaissance Faire, which was created by Phyllis and Ron Patterson, a couple living in California, in the early 1960s.5

As this wonderful article from Smithsonian Magazine explains, Ron was an art director for a marketing agency, and Phyllis was an English, history, and drama teacher who left the public system in 1960 because she refused to sign an oath of political loyalty. While staying home with their young son, Phyllis worked part-time as a private theater arts teacher, and in 1963 she and her husband had the bright idea to build a Renaissance-style commedia dell’arte wagon. They set it up in the backyard of their Laurel Canyon home, and the shows they put on with their students were such a success that they started thinking bigger.

Like many other actors and creatives in California at the time, many of the Pattersons’ friends had been blacklisted by the McCarthy administration for suspected communism, leaving them with plenty of free time. Together, they decided to hold a two-day “Pleasure Faire” in May 1963 at a friend’s nearby ranch to benefit local radio station KPFK. Their Pleasure Faire would feature immersive acting, shows and games, demonstrations by craftsmen, and plenty of more and less-accurate food. The Faire was entirely volunteer-run: most of the decor and costumes were made from donated or salvaged material, and actor friends staged scenes from Shakespeare plays throughout the weekend.

’The fair…was the first gathering of alternative types that I knew of in Los Angeles, and it had [an] intellectual focus on the history of an era of awakening from the Dark Ages in Europe (as we were awakening from the Dark Ages of McCarthysim,” attendee Alicia Bay Laurel told historian Rachel Lee Rubin, as recorded in Well Met: Renaissance Faires and the American Counterculture.

The Faire was a huge success, attracting hundreds of guests and raising $6,000 for KPFK (around $61,000 today). Those numbers only went up in the follow years, as did the entertainments: this poster from the third annual faire (created by Ron Patterson) promises “jesters, jugglers, pipers, piemen, mummers’ plates, magick, tarts, pottery, Punch & Judy, hawkers, kites, dartes, poney carts, parades, tunics, flowers, food mongers, strolling minstrels, archery, gingerbread, commedia players, lusters & divers other crafts sold from Medieval Waggons.”

Some, however, thought there was too much focus on pleasure at these Pleasure Faires. Local naysayers - many of them the same people who had reported the organizers as suspected communists years earlier - tried to get the Faire shut down, claiming it was a hotbed of “sin and debauchery.” According to KPFK producer David Ossman, one local paper’s headline was “Sheriff Ready. Proponents of Free Love, Free Dope and Free Education Join Forces to Deceive the Unwary.”

Though the organizers were able to temporarily maintain their permit for the Faire on educational grounds, the controversy that summer ultimately led to the Pattersons and KPFK parting ways. In 1968,the Pattersons established the Renaissance Centre, with a focus on year-round education about the Early Modern period.

In the years that followe, more than 200 Renaissance Faires appeared across the country, becoming known as places to celebrate the loosely-connected pleasures of old-fashioned entertainment, playing dress-up, and free-flowing alcohol.

As Neil Steinberg writes in 2007 for The Chicago Sun-Times, describing the broad appeal of Ren Faires:

If theme parks, with their pasteboard main streets, reek of a bland, safe, homogenized, white-bread America, the Renaissance fair is at the other end of the social spectrum, a whiff of the occult, a flash of danger and a hint of the erotic. Here, they let you throw axes. Here are more beer and bosoms than you’ll find in all of Disney World.

Fifty years after the Pattersons and KPFK, this debate rages on. Are Renaissance Faires meant to be history-tinted theme parks full of debauchery and silliness? Or, as the Pattersons decided, are Renaissance Faires places for education and re-enactment, a window into history? What are the stakes of looking at history through the lens of the Renaissance Faire?

Dangerous Myths

Contemporary historians are divided on their attitudes towards Renaissance Faires, and closely related events and organizations like the Society for Creative Anachronism (SCA), which hosts similar gatherings but with far stricter rules regarding historical accuracy.

On the one hand, some historians argue that these events can be great opportunities for educational outreach, allowing academics to connect with people who are interested in learning more about history. Furthermore, they tend to involve close-knit communities of artisans and enthusiasts who are connected by their shared activities and interest in keeping endangered knowledge-ways alive. As historian Ken Mondschein writes in an article about the SCA, “It is a place where people can feel welcome, make friends, and form romantic relationships. In a world where community is being replaced by targeted marketing and real-world interaction by screen time, the SCA provides the social contact that’s essential for human wellness.”

Proponents of Renaissance Faires also argue that they allow members of the larger community to connect with craftspeople and learn more about how goods are produced, encouraging them to think more deeply about everything from how their clothes are made to where their culinary traditions come from.

Other historians, however, object that contemporary Renaissance Faires - with their cosplayers, jumbles of anachronisms, and vendors hawking cheap drop-shipped goods, are hardly sites for thoughtful and accurate education. “I abhor medieval fairs,” declares history professor Michael Vargas in a blog post. After listing a series of complaints about their faux-historical aesthetics, mishmash of time periods, and general silliness, he arrives at the crux of his argument: Renaissance Faires contribute to a romantic fantasy of a white European past that is deeply attractive to white supremacists.

Vargas has a point: there have been numerous examples in the last decade of connections between the alt-right and the cluster of activities and interests you’ll find at the Renaissance Faire. As this 2017 Daily Beast article reports, Paul Walsh, a neo-Nazi who attended the deadly Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, had been active in live action role play (LARP). The majority of the Massachusetts' Renaissance Faire’s performers resigned in 2021 after discovering one of the Faire’s co-owners was a conspiracy theorist with ties to the alt-right. And, though not inherently problematic, historical symbols such as Viking runes and Thor’s hammer are frequently appropriated by white supremacists.

As Vassar history professor Dorothy Kim explains:

White supremacists and other "alt-right" types imagine medieval Europe as the last cultural space of pure white history that they can basically hook themselves into and argue that there were no people of color present. They’re very interested in how Western Europe becomes this kind of idealized white beginning and origin myth. It’s not a surprise, for instance, that in Charlottesville the white supremacists were carrying torches and circling around Jefferson's statue. He wanted Virginia to be Anglo-Saxon England. We know from medievalists and scholars that, for instance, after their defeat, the former Confederate states became very interested in thinking of themselves as the defeated Anglo-Saxons after the Norman foreigners basically took over. We also know the Ku Klux Klan is obsessed with white knights. This has had a long history in American culture and history.

This modern, romanticized image of the white European Middle Ages was also popular in Great Britain in the nineteenth century, during the height of its colonial power. As the British Empire forced people from around the world to adopt their cultural norms and traditions, they told and retold stories that emphasized the beauty, splendor, and nobility of their own homeland.

Pointing to the signing of the Magna Carta in 1215, British historians argued that England was the birthplace of democracy. Queen Victoria incorporated medieval symbolism into her pageantry, and wealthy individuals throughout the empire frequently dressed up in medieval or renaissance-inspired costumes. Alfred, Lord Tennyson published the epic poem cycle Idylls of the King about the King Arthur myths, and in 1839, the Eglinton Tournament, a historic re-enactment, drew over 100,000 visitors.

The ballad I chose for Song of the Week, by the way, is one such work of medieval revisionism. Set in a magical pre-modern world, “Reynadine” tells the story of how a were-fox seduces a woman and takes her to his castle and an unknown fate. While Reynard the Fox is a common figure who appears throughout 12th century literature, the ballad first appears around the year 1800.

This fantasy of the white Middle Ages, Kim reminds us, is just that: a fantasy. Depictions of the European Middle Ages as uniformly white and Christian aren’t historically accurate: medieval Europe included people of multiple races and religions, as well as a great deal of social and cultural movement. Furthermore, she points out, “medieval Western Europe was really considered the hinterlands, the proverbial outskirts or boonies. Actual innovation in the medieval world was coming out of the medieval Mediterranean, and was coming viia medieval Islamic culture.”

Sometimes, however, white supremacists hide behind claims of historical accuracy in order to maintain their innocence. One of the most notorious examples of this occurred in 2018, at an event by the Society for Creative Anachronism. As Ken Mondschein explains for The Public Medievalist, two high-ranking members of the society, using the pseudonyms “Athanaric” and “Sigriðr,” wore costumes to a major event that were decorated with woven trim containing swastikas and the letters “HH” (for “Heil Hitler.”)

When members complained, the offenders claimed innocence, saying they “got very exited [sic] about a piece of very complex historical art and making an extremely accurate presentation and felt the difference to modern interpretations would be sufficient and that everyone would agree with us.”

Here’s where things get complicated. The sash really was an accurate reproduction of an ancient Norse sword belt dating from the 6th century AD. It was found in 1933 in an archaeological dig in southern Norway. The seeming “H” symbols are the ancient rune Hagall.

That does not, however, mean that the re-enactors were innocent. The Nazis knew about this sword belt, and they saw it as an authentic piece of “Aryan” heritage. Despite the fact that the Norwegians hid the original artifact, the Nazis made replicas of the sword and belt, and they appropriated its symbols as their own, using them throughout their art.

Today, of course, when we see a swastika, we immediately think of the Nazis and all they stood for, not of a beautifully woven ancient belt. Allegedly, Sigriðr knew about the history of the belt, and had been confronted by SCA members five years before for wearing items with swastikas on them. Regardless of their claims of innocence, the entire situation is suspect.

As textile scholar and SCA member Lisa Evans points out, “There are many equally old, equally documentable weaving patterns that do not have the history of these motifs...Despite its historicity, swastikas for personal heraldry were banned within three years of the SCA’s founding.” At a certain point, some symbols have evolved to be unmistakably associated with hatred and bigotry despite their historical origins, and that meaning takes precedence.

So, with all of this complex and troubling history in mind, am I suggesting that we give up on Renaissance Faires altogether? Have these events strayed irredeemably far from the liberal and inclusive vision of Phyllis and Ron Patterson?

Riposte

I don’t think so - but there are some practical ways to fight back. If you want to attend a local Renaissance Faire or get involved in a similar event, look into the Faire’s organizers and history to make sure there are no racist dog whistles or red flags. If they haven’t already made a public commitment to diversity and inclusion, like that adopted by the Society for Creative Anachronism, then encourage the organizers to do so. If you spot white supremacist symbols or objects being sold by a vendor, alert the organizers of the event. And, if you’re involved in organizing a local Faire, make sure that you vet your vendors thoroughly, and hire diverse performers and staff.

There are actions you can take year round as well: read books about the complexity and diversity of the real Middle Ages and Renaissance, like Geraldine Heng’s Empire of Magic: Medieval Romance and the Politics of Cultural Fantasy (2004) and Jonathan Hsy’s Trading Tongues: Merchants, Multilingualism, and Medieval Literature (2013). And, when you’re enjoying stories set in a fantastic version of those worlds - where the only limits are our imagination - try to include some more diverse ones. Some of my recent favorites have been Nimona, The Green Knight, and Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves.

It would be a real shame, I think, to abandon Renaissance Faires to the worst of their fans, when the truth is that they can be spaces for so much imagination, community, and joy.

The truth is that we attended our local Renaissance Faire this weekend not out of some deep desire to reclaim or even learn much about the past, but simply because it was fun.

It was fun to sew a matching vest and bodice for Taylor and I out of a thrifted IKEA bedspread. It was fun to shout “huzzah!” for the knife juggler and boo Guy of Gisborne in his archery competition against Robin Hood. It was fun to adorn ourselves in flowers, and to take photos pretending we were on the cover of a romance novel, and to picnic together in the grass.

And it was particularly fun for me, this time, to pretend to be a bard, and to write flash poems on parchment for vendors, about the works of art they had carefully crafted.

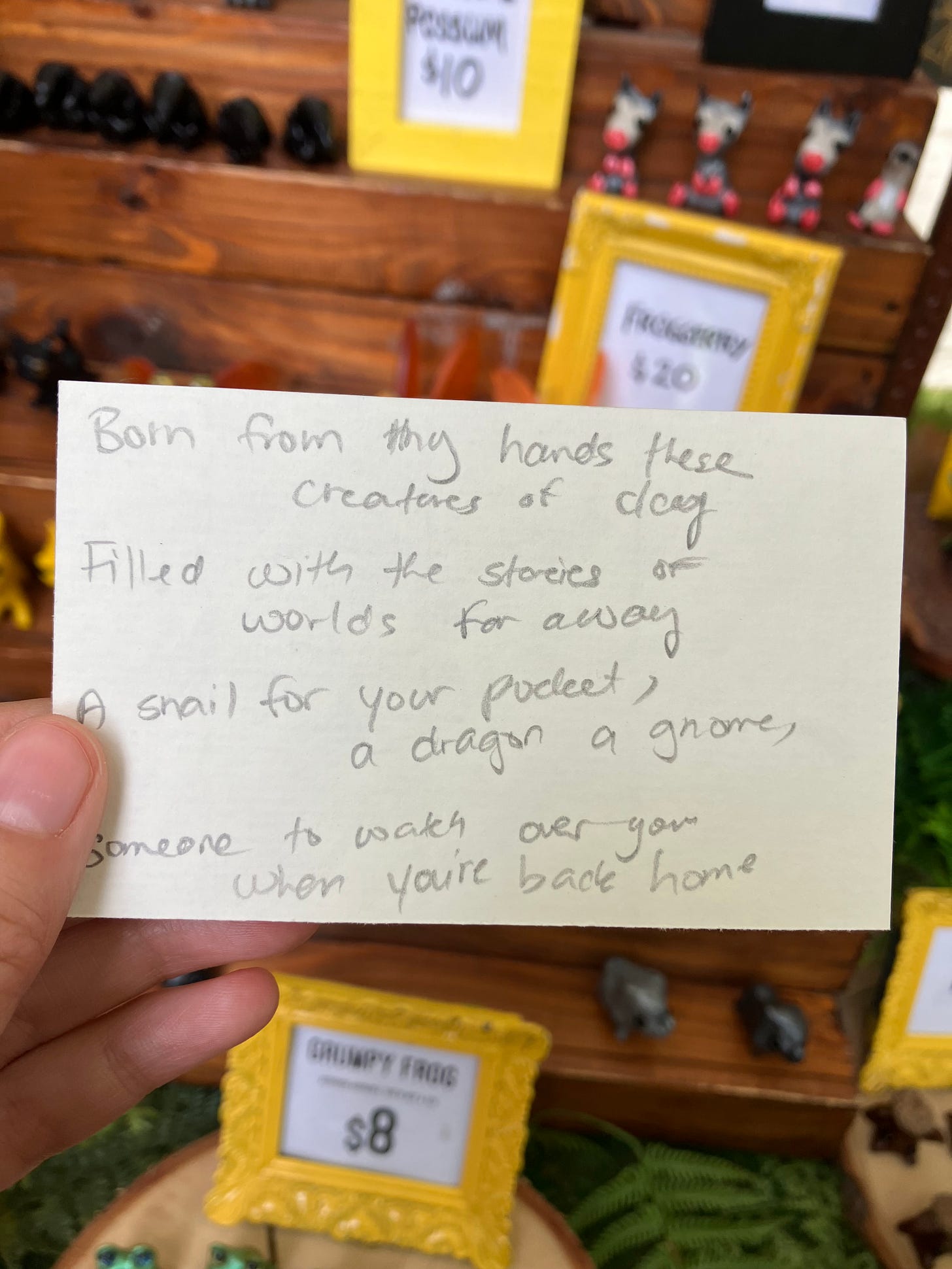

Like this one, which I wrote for a woman who made tiny weird creatures out of polymer clay:

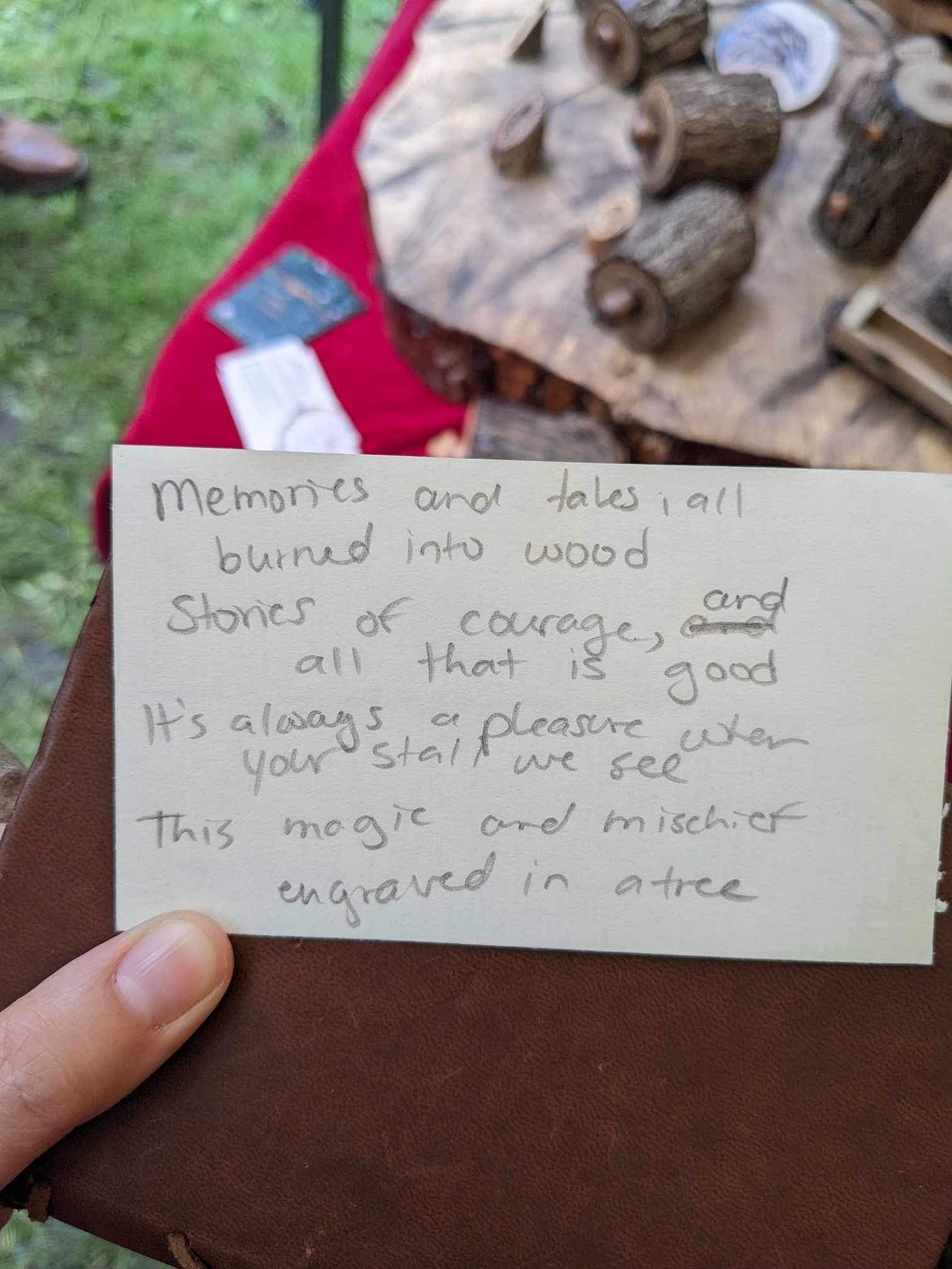

Or this one for the lovely mother-daughter pair who we have bought wood-burned art from at three different local festivals and markets.

At their best, Renaissance Faires remind us of what Phyllis and Ron Patterson knew: that, in the words of J. R. R. Tolkien, “If more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world.”

We may never be able to fully access the past - nor should we try to cling to its values. It is up to each of us to build communities that can imagine something better: a future where everyone is welcome.

When it comes to Renaissance Faires, what should I add to my Syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

The Carolina Chocolate Drops was a band (2005-2012) consisting of Rhiannon Giddens, Rowan Corbett, and Malcolm Parsons, all Black musicians committed to creating music in the often-overlooked tradition of African American folk, especially from North and South Carolina. Their 2010 album Genuine Negro Jig won the Grammy Award for Best Traditional Folk Album. I learned about Giddens, a banjo player and music historian, from her appearance on the “Neon Moss” episode of Dolly Parton’s America which I talked about two weeks ago. Many others have encountered her recently without realizing it: she plays banjo and viola on Beyoncé’s “Texas Hold ‘Em.”

It also features a wonderful ensemble cast, including Alan Tudyk and Paul Bettany as my first exposure [heh] to Chaucer.

The joke is that they’re on an away mission, or time-traveling. Many Renaissance Faire purists hate the often-repeated Star Trek cosplay ‘joke,’ and think it makes light of their commitment to historical accuracy. Other Faires address this by having specific “time traveler” themed weekends.

Last year, I bought a belt buckle and a bone-handled replica fork from them for my brother Paul, who is an archaeologist. This year I picked up a kit for a lucet, a wooden tool used by Vikings and Anglo-Saxons to make braided cord.

After the debacles that were corsets and dandelions, you have no idea how relieved I was to discover how straightforward and well-documented history of Renaissance Faires was.