Song of the Week: “Coat of Many Colors,” by Dolly Parton - “I told ‘em of the love / my momma sewed in every stitch.”

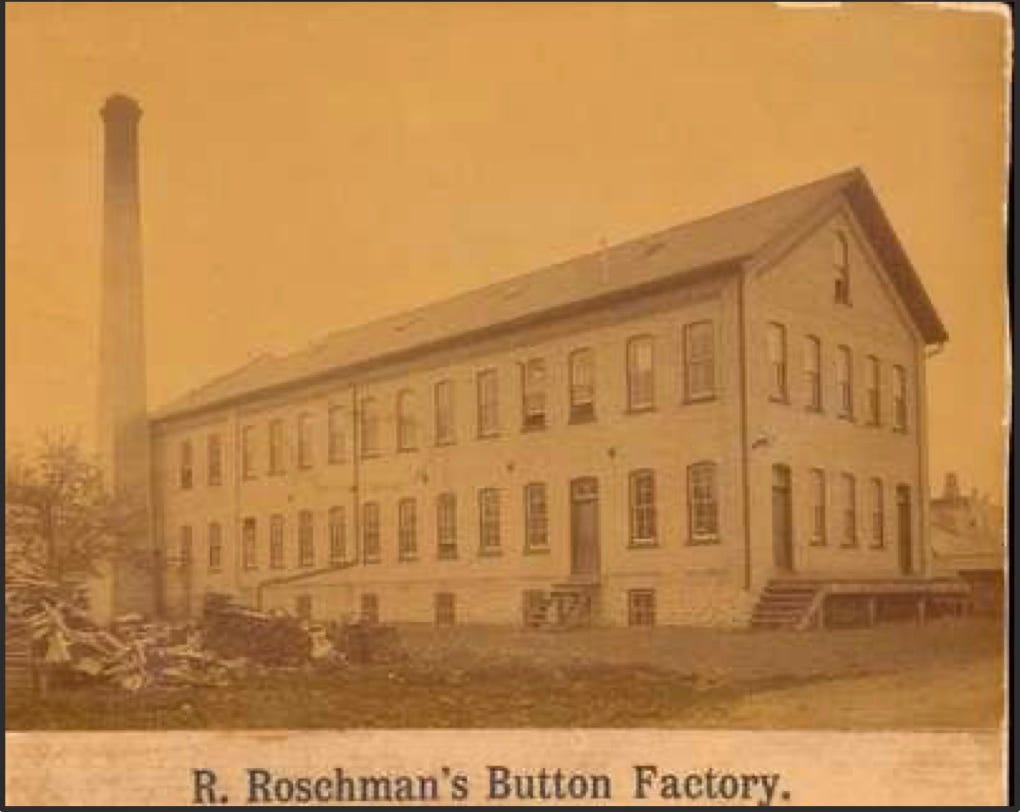

Last weekend, I got to take an art class in a factory built by my great-great-grandfather.

It’s the stuff of family legend that my great-great-grandfather, Richard Roschman, stowed away on a ship bound for Canada to avoid being drafted in the Franco-Prussian war, and eventually ended up the town of Berlin (now Kitchener), which had a large population of German immigrants.

A few years later, Richard’s brother Rudolph came to join him in Canada, and in 1886 the brothers opened the Roschman Button Factory, where more than 100 workers created buttons out of shells, wood, and other natural materials. The business thrived until the introduction of cheap plastic buttons and zippers in the 1940s put the family factory out of business, depriving me of the chance to be a button factory heiress!1

In the 1990s, the long-empty button factory was re-opened by the city as Button Factory Arts, a non-profit community art centre and event space that hosts weddings, yoga, exhibitions, and arts and crafts classes. And so, naturally, when I decided I wanted to learn a new craft this winter, I turned to the button factory to teach me.

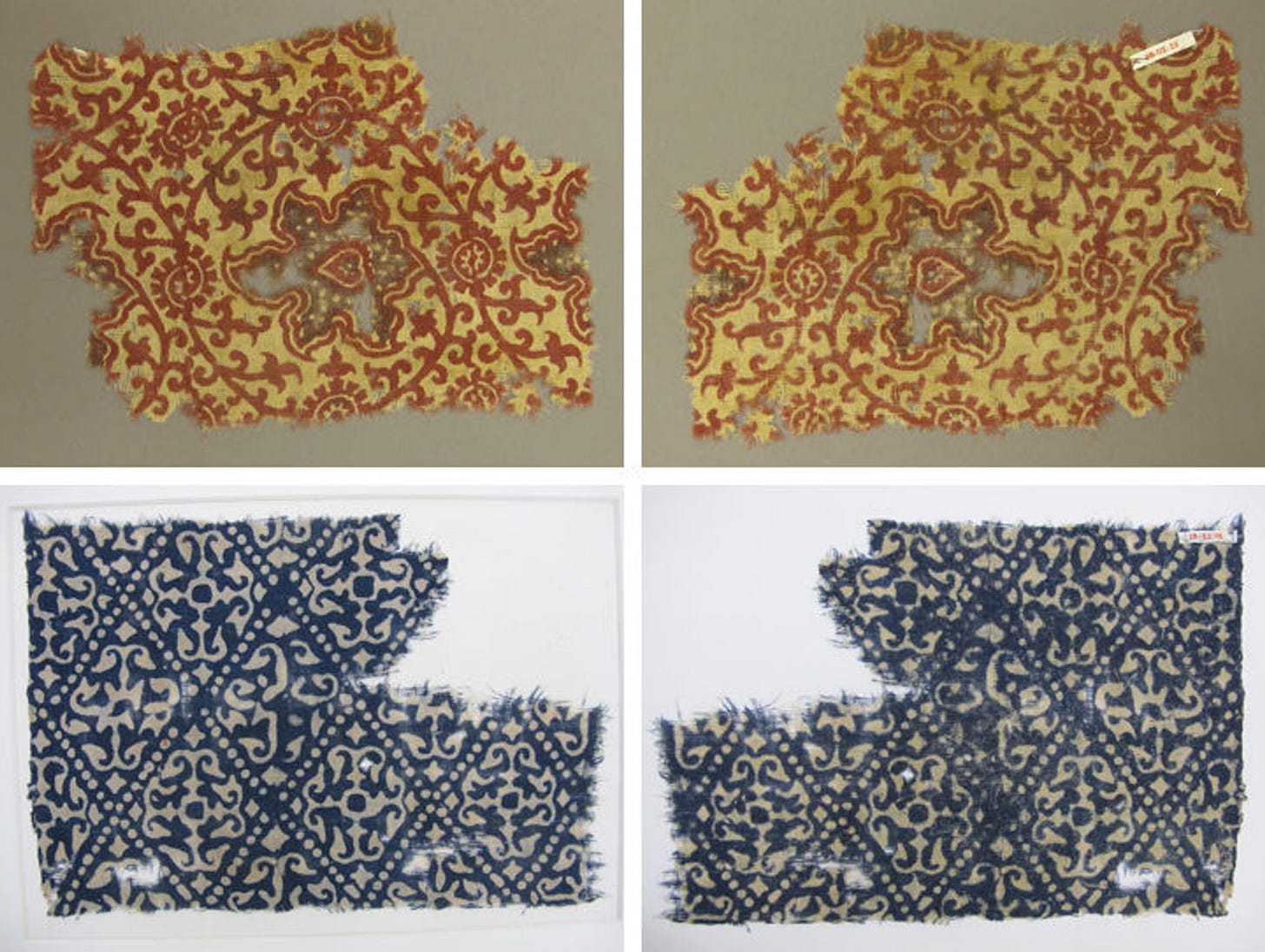

Thanks to a gift certificate my parents gave me for Christmas, I spent Saturday in a six hour workshop on block printing. Our teacher, an Indian artist named Susha Suresh, began the day with a presentation on the ancient history of wooden block printing on the subcontinent.

Block printing in India is thought to be 2000 years old; the oldest known samples, from the 14th century, are actually exports that were found in Egypt, but are printed with motifs that clearly identify them with contemporary art in India.

Each region of India developed its own distinct style and technique of block printing on fabric: in northern, Muslim-dominated regions, fabric was printed with heavily-detailed, ornate patterns printed in red and blue. In the middle of the country, where the weather was very hot, artisans favored simple geometric patterns on breathable cotton. And in the south, creators from the Rajasthan desert used “dabu,” a mud made from gritty desert sand to resist-dye intricate patterns onto fabric, similar to batik or tie-dye.

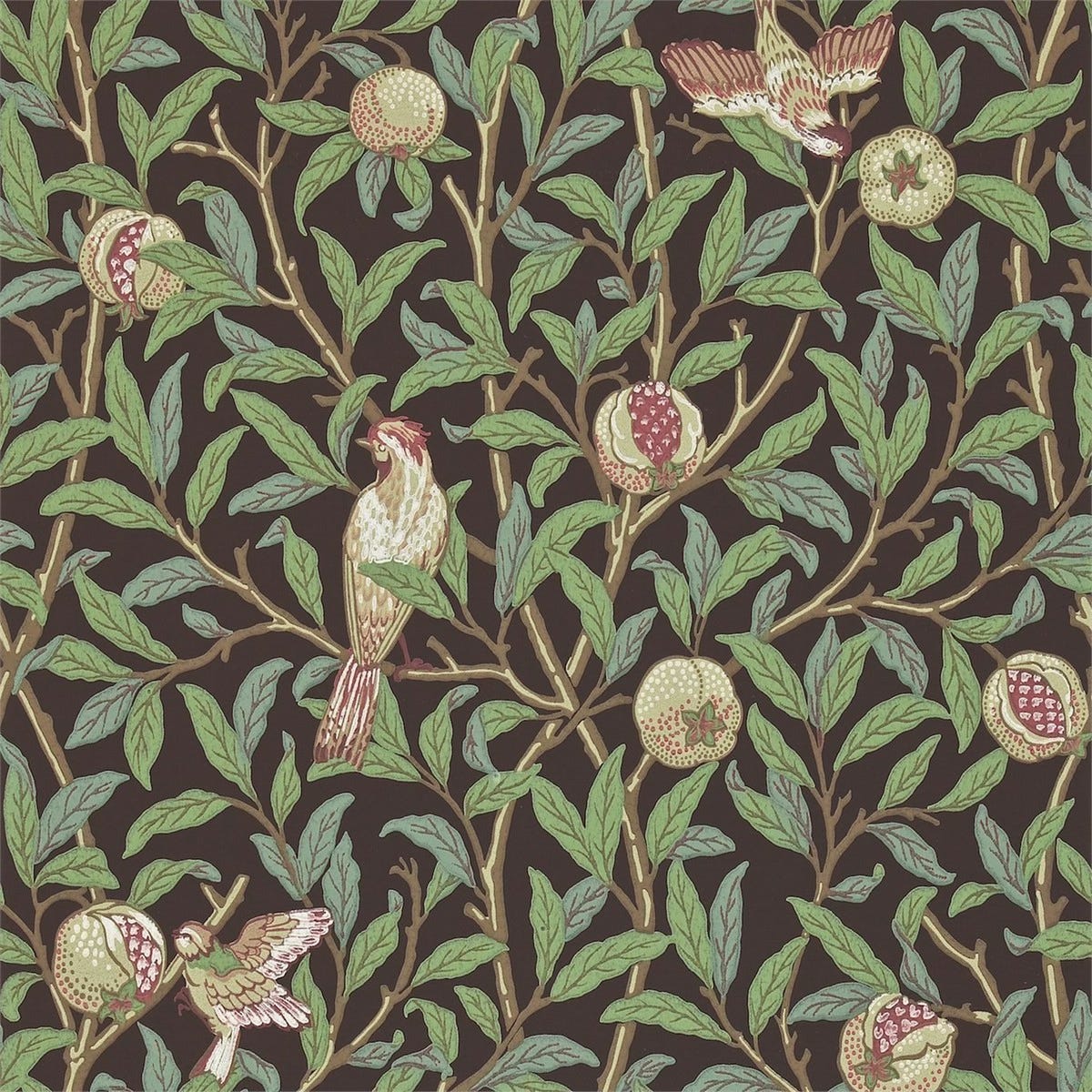

Regardless of region, however, all of these fabrics were decorated using incredible wooden blocks hand carved by skilled tradesmen whose families had been doing the same name for generations. The blocks are carved using needles and tiny chisels from wood that has already been soaked in oil for several weeks to soften and preserve it. Then, the pattern is painstakingly printed onto the fabric one piece at a time, with each color in a pattern designed, carved, and printed separately.

Though synthetic dyes, mass production, and fast fashion account for much of the fabric in India today, traditional block printed textiles still endure; a recent Vogue India article highlights three modern fashion labels who still proudly incorporate hand-printed fabrics into their collections.

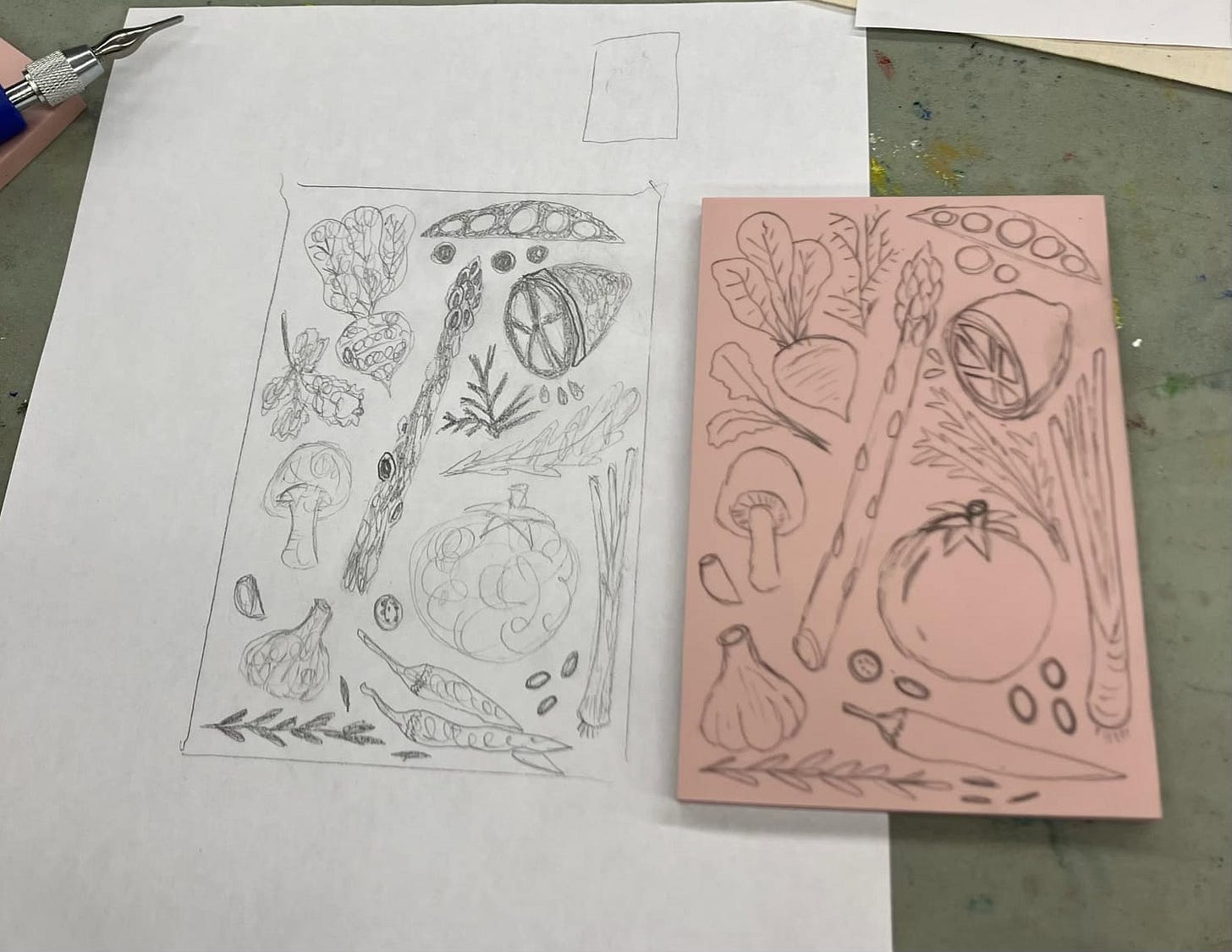

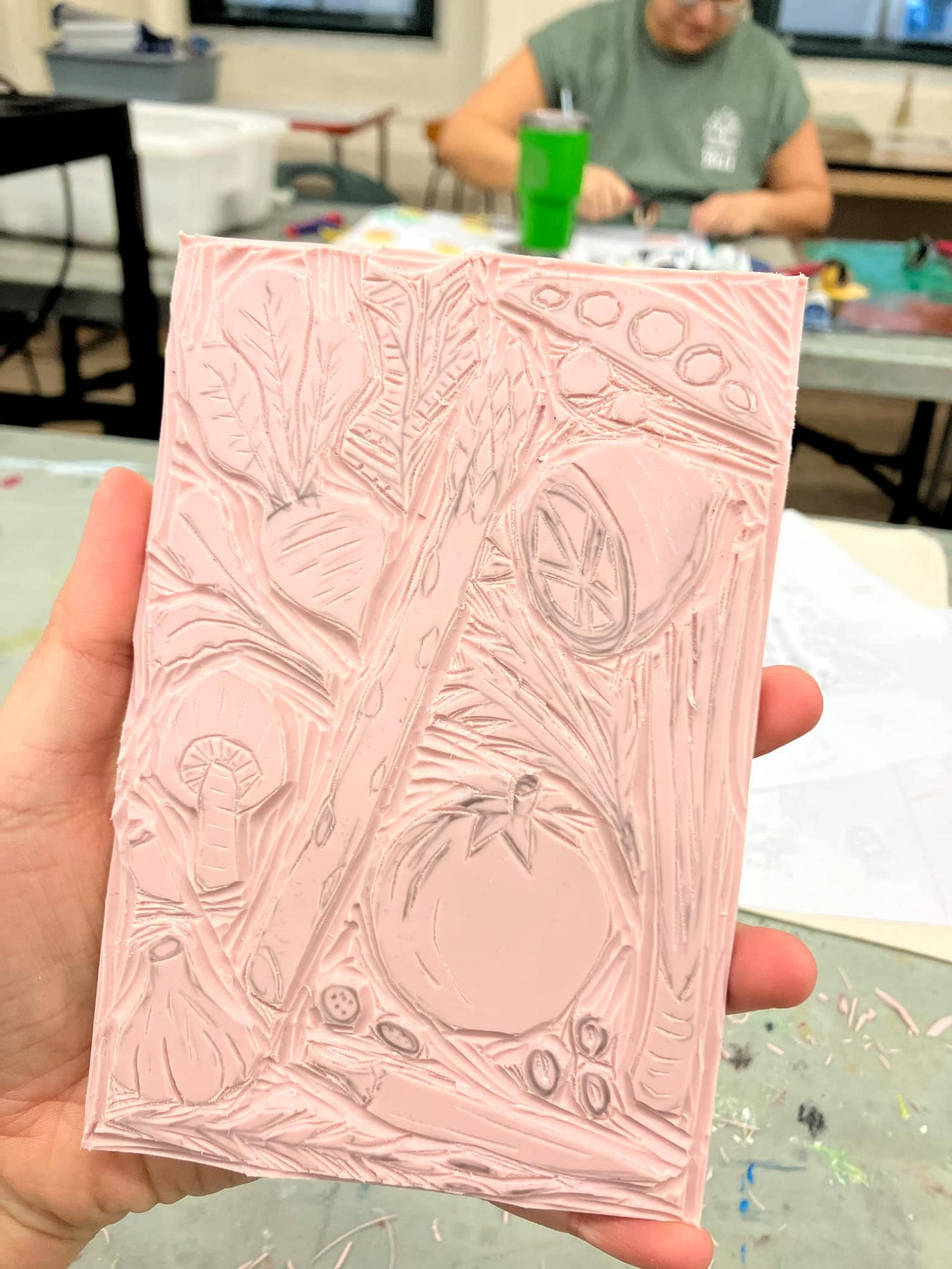

After our teacher took us on this kaleidoscopic tour of printmaking techniques, we had the humbling experience of designing, carving, and printing our own blocks, albeit in the much easier and more forgiving medium of soft linoleum. We sketched out simple designs, pencilled them onto the provided pink blocks, and then used wedge-shaped tools to painstakingly carve away strips until only our drawings remained.

There was something deeply therapeutic about turning all of my focus to this little 4x6 block and slowly subtracting from it a sliver at a time with a tool only a little bigger than a needle. It was an act of faith, of sustained intention.

When I finally rolled ink onto my finish block - an arrangement of my favorite vegetables inspired by the veggie-print overalls I wore to the class - I gasped with delight as my design suddenly, vividly materialized. It reminded me of when I took a film photography class my first year of university. I’d sit in the dim red light of the dark room patiently exposing my film and measuring out chemicals, then watch the images melt into being before my eyes.

Block printing is magic: magic I made, one step at a time, using imagination and the methodical work of my hands.

Utopia

A week before I took the class, I had already encountered wooden block printing, in the second Fabric of Britain documentary episode. As you may remember, I watched the first episode, about the history of knitting, for a Syllabus back in November. This episode was about the even sexier and more scintillating subject of…wallpaper.

Wallpaper was introduced to Great Britain in the 17th century, when it was made by artisans who glued individual pieces of paper together into long sheets and then carefully stamped them with carved wooden blocks so heavy they had to be operated with small pulleys. This process was so painstakingly slow that wallpaper was immensely expensive, and was favored mostly by the upwardly mobile who wanted to reproduce the look of the heirloom fabric wall hangings displayed by those with ancestral wealth.

The Industrial Revolution brought innovations in paper production and mechanized printing, allowing the mass production of wallpaper and putting the decorations in reach of the middle and working class. At the same time, however - as in all industries - the production of this wallpaper was hazardous to the workers: it employed synthetic, often toxic dyes; heavy and dangerous machinery; and poorly-ventilated, noisy working conditions.

It was a disgust with these working conditions that drove William Morris (1834-1896) - today remembered as the most famous wallpaper designer of all time - to help create the Arts & Crafts Movement.

As Pamela Todd explains in her encyclopedic book The Arts & Crafts Companion, the Arts & Crafts Movement “sought to stem the tide of Victorian mass production, which its adherents believed degraded the worker and resulted in ‘shoddy wares.’ The movement redefined the role of art and craftsmanship, sought to restore dignity to labor, created opportunities for women, and underpinned many social reforms” (11).

The movement’s founders shared a democratic impulse and a fundamental belief that the dignity of the worker and the quality of the work were connected. They condemned the ways in which the Industrial Revolution had alienated workers from their labor, taking them out of nature and into dangerous, filthy conditions. The founders believed that art and beauty should belong to everyone, and that workers should be able to build lives enriched by art, pleasure, and community regardless of class.

As Walter Crane wrote in 1893:

The movement ... represents in some sense a revolt against the hard mechanical conventional life and its insensibility to beauty (quite another thing to ornament). It is a protest against that so-called industrial progress which produces shoddy wares, the cheapness of which is paid for by the lives of their producers and the degradation of their users. It is a protest against the turning of men into machines, against artificial distinctions in art, and against making the immediate market value, or possibility of profit, the chief test of artistic merit.

It also advances the claim of all and each to the common possession of beauty in things common and familiar, and would awaken the sense of this beauty, deadened and depressed as it now too often is, either on the one hand by luxurious superfluities, or on the other by the absence of the commonest necessities and the gnawing anxiety for the means of livelihood; not to speak of the everyday uglinesses to which we have accustomed our eyes, confused by the flood of false taste, or darkened by the hurried life of modern towns in which huge aggregations of humanity exist, equally removed from both art and nature and their kindly and refining influences.

They sought to unite form and function, stressing the importance of care and quality of craftsmanship regardless of the medium. Arts & Crafts Movement members created building, furniture, textiles, wallpaper, stained glass, ceramics, metalwork, jewelry, and books, all thoughtfully designed and made almost entirely by hand. William Morris, for example, made wallpaper using the old style of enormous carved wooden blocks. One roll of wallpaper often took four weeks to create!

Drawing on an idealized version of Medieval craftsmen’s guilds, the movement’s leaders tried to create model communities where artisans could practice creative expression and take pride in their labours.

Architect C. R. Ashbee, for example, created a Guild of Handicraft in the impoverished East End 1888, so as to train workers to make skillful, beautiful things. The business was successful enough that in 1902 he then moved his whole group of craftspeople to the rural Cotswolds, where he built them a model community, allowing them to live and work in comfort and with care. One hundred and fifty Londoners moved to the country, where Ashbee provided them with “not just homes, but gardens, a swimming pool, and communal activities including amateur theatricals and musical evenings” (Todd 17).

Unfortunately, as with all utopian visions, the movement eventually came to an end. Because of its founders’ insistence on making everything slowly and carefully from scratch, most of the beautiful things they made were too expensive to be purchased by anyone except the wealthy, undercutting their democratic ideals. At the same time, enterprising business owners began making cheap, mass-produced knock-offs of Arts & Crafts Designs, copying the popular “cottage aesthetics” without quality craftsmanship or humane treatment of their workers.

By 1907, Ashbee’s model village of craftsmen was financially insolvent, and a few years later, World War I brought the last utopian gasps of the Arts & Crafts Movement to a halt. “ “We have made of a great social movement, a narrow and tiresome little aristocracy working with great skill for the very rich,” Ashbee despaired in his journal.

Even as the Arts & and Crafts Movement floundered in Britain, however, it endured in the United States, albeit in a less idealistic form. American designer Gustav Stickley was inspired by the movement’s ethos and designs during a trip he took to England in 1898, and decided to bring the philosophy home with him. He was less skeptical, however, towards marketing and machines, arguing that machines could liberate workers from “tedious and unnecessary labour” (23). As a result, the American Craftsman movement, which attracted such high profile members as Frank Lloyd Wright, endured until the onset of the Great Depression in 1929.

“Inevitably, this mean that Morris’s ideas were diluted,” Todd writes, “yet paradoxically they reached a wider audience and were made to work in a way that he himself had failed to achieve because of his insistence on expensive handcrafting and his unwillingness to market himself” (30).

“We All Had to Believe in It”

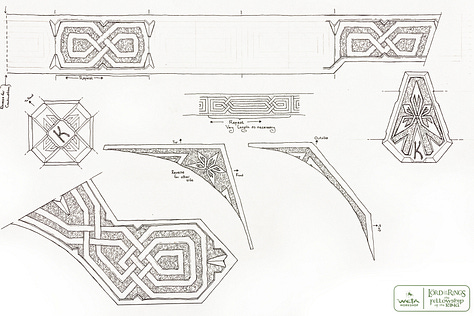

I’ve always loved production design: storytelling manifested through the objects that build a world on stage or on screen. My introduction to the care and attention that goes into production design was, of course, The Lord of the Rings: specifically, the hours of behind-the-scenes “Appendices” included with the Extended Edition DVDs. While the movies sparingly employ computer generated special effects, they still look so good more than twenty years later because so much of what you see on screen was really there.

Wētā Workshop, the New Zealand-based production company that helped bring Middle Earth to life, created a staggering number of physical objects for the films: 48,000 pieces of armour; 10,000 arrows; 19,000 costumes; 1,800 pairs of hobbit feet for the four lead actors; and twelve highly detailed models of buildings nicknamed “bigatures,” the largest of which was almost 30 feet tall. Complicating matters even further, because hobbits are half the size of humans, versions of many props had to be made identically on different scales.2

Two of the most influential Tolkien artists, John Howe and Alan Lee, were brought in to create a consistent visual look for the films, and each different culture in the films was carefully developed to have its own style, color palette, and techniques: the hobbits were based on the nineteenth century British countryside, Rohan on Anglo-Saxon artifacts found in Sutton Hoo, the elves on Art Nouveau design, and so on. And then, of course, costumes and props were carefully weathered to make them look ancient, damaged, or travel-stained, not fresh out of the workshop.

As Peter Jackson explains in a 1998 interview about the films’ production, “It might be clearer if I described it as an historical film. Something very different to Dark Crystal or Labyrinth…it should have the historical authority of Braveheart, rather than the meaningless fantasy mumbo-jumbo of Willow.”3

One of my favourite examples of the staggering craftsmanship that went into every frame of the films is the 22 kg suit of armour worn by Théoden, King of Rohan.

The armour, which is made mainly of leather and brass, is covered in motifs from Rohan’s history, as well as numerous references to their beloved horses. Individual scales of the armour - far too small to be seen in detail on screen - are engraved with horse heads. Bands of leather along his sides depict a boar hunt. And, absurdly, the symbols of Théoden’s royal line are engraved on the inside of his armour, where no one but actor Bernard Hill would ever see them.

“That’s just so great,” Hill reportedly said when he first saw it while dressing. “That makes me feel like a king.”

The level of astonishing care and attention to detail that went into Jackson’s vision of Middle Earth is, I believe, a huge part of why the films endure. By creating something with such detail and care that there is always something new to admire, the filmmakers encourage us to keep returning for another look.

A similar ethos to Jackson’s drove the creation of a very different movie two decades later: Greta Gerwig’s Barbie (2023). Barbie was a surprise critical hit and cultural phenomenon the summer it came out, not only because of its witty script, catchy music, and memorable performances, but also because of the care that went into creating its dazzlingly pink onscreen world. “It was one of the most difficult, philosophical, intellectual, cerebral pieces of work we’ve ever done,” says Oscar-winning production designer Sarah Greenwood, who has worked on historical films including Atonement, Anna Karenina, and Darkest Hour.

“We all had to believe in it as much as if it was a space movie or a period movie,” says set decorator Katie Spencer. “We had to research it as though it was set in 1780.” The designers painstakingly considered how to translate the look of vintage Barbie Dreamhouses to film, making rooms 23% smaller than life-sized to ensure the actors looked doll-like. They used techniques borrowed from old soundstage musicals to create 800-foot hand-painted backdrops for scene backgrounds. And they eliminated the natural colours of black, brown and white from Barbie’s world, instead filling it with so much fuschia that they inadvertently caused a worldwide shortage of pink paint!

While I cannot prove one way or another that Barbie succeeded because of this loving attention to detail, it is certainly an aspect of its production that was loudly appreciated by its fans. The comments on that Architectural Digest video attest to this. “It’s so refreshing to see ACTUAL SETS, and not everything done with CGI,” writes one commenter with more than 16,000 upvotes. “Kudos to Greta Gerwig and the designers and artists.”

“Great stuff,” writes another person with 13,000 upvotes. “I love the minimal amount of cgi and monumental amount of handcrafting and workmanship that went into it.”

Film offers us a fascinating study in accessible craftsmanship, one that Morris and his contemporaries could never have dreamed of. Even if viewers might not be able to afford hand-embroidered textiles or intricate stained glass for their homes, most of us can buy a movie ticket. In our hyper-connected, frenetic world, our attention is our greatest currency - and we can choose to spend it on things made beautifully and with great care.

Diabolus Ex Machina

I have been a loud and stringent critic of generative AI since it rose to prominence a couple of years ago, and my conviction has only grown stronger.4

Even if there was no other ethical or aesthetic issue with it, AI is disastrous for the environment: sending one email using Chat GPT vaporizes an entire bottle’s worth of drinkable water. As AI grows in popularity, its enormous energy consumption will only grow.

I have written before, as well, about AI’s threat to our already precarious political and social lives; deepfake technology is already being used to rapidly propagate misinformation and diminish public trust.

I also condemn AI as a worker. As a writer, whose craft and training have already been devalued for years, I’ve seen the ways that generative AI has quickly eroded societal appreciation for the labor that goes into writing, painting, graphic design, filmmaking, and other arts.

AI threatens to steal jobs from millions of people whose employers are more interested in maximizing profit than prioritizing creativity, critical thinking, and quality. And, it is only able to do what it can do because it is a monster that feeds on work stolen from real artists. In a class action lawsuit against AI company Midjourney last year, artists alleged that their work had been used to train generative AI models without compensation. The successful 2023 Screen Actors’ Guild and Writers’ Guild of America strikes were partially in protest against studios’ attempt to replace creatives with AI trained on their work. I am very grateful for the fact that Substack allows authors to opt out of their work being readable by AI; for now, at least, Syllabus is free from the monster’s jaws.

But beyond all of the practical reasons why I think that generative AI is both sinister and destructive, I am opposed to it because I believe it represents a fundamental misconception about the purpose and value of art. AI-generated art and writing has no perspective, no intention, no curiosity, no wonder. It is the logical end product of a complete lack of respect for worker and for workmanship, a simulacrum of meaning that prizes laziness and ease of acquisition over craftsmanship, creativity, and skill.

And I am not alone in feeling this way. The legendary Japanese animator and Studio Ghibli creator Hayao Miyazaki, when shown animation created by an AI program, recoiled in horror. “I am utterly disgusted,” he says. “I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself.”

Filmmaker Guillermo del Toro made a similar statement while doing press for his 2022 Pinocchio, which was created using stop-motion animation that took over 1000 days to film. “I think that art is an expression of the soul,” he said. “At its best, it is encompassing everything you are. Therefore, I consume, and love, art made by humans. I am completely moved by that. I am not interested in an illustration made by machines and the extrapolation of information.”

There is a place, surely, for the mass production of insulin and soap and batteries and other necessities, that make life easier and less filled with suffering. But we do not need to mass produce art.

As writer Joanna Maciejewska quipped, “I want AI to do my laundry and dishes so that I can do art and writing, not for AI to do my art and writing so that I can do my laundry and dishes.”

We should not seek to avoid the long, often frustrating process of creation because it is difficult or time consuming. We should not shy away from the real work it takes to learn skills, to hone crafts, to try and fail and learn every time. We make art because the making of the art is as rewarding as the finished product. We make art because it makes us human.

Perhaps my work is as doomed as that of my ancestor, whose handmade shell buttons were made obsolete by zippers and plastic. But I refuse to love the machine. I remain ever the utopian, loving only human hands, and the things they craft.

When it comes to craftsmanship, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

I am the eldest child of the eldest child in every generation going back to the founder, Richard. Also, my father is named Richard Roschman too!

Jillian and I got to see many of these props in person when we toured Wētā in Wellington, New Zealand, and they’re pretty astounding in person. Unfortunately, we weren’t allowed to take pictures, so you’ll have to go see for yourself!

I feel like Jackson is a little unnecessarily cruel to Willow, here, which had some innovative-for-1988 special effects and did a great job of feeding my fantasy obsession as a kid in the year in between the releases of The Fellowship of the Ring and The Two Towers.

I use the phrase “generative AI” here intentionally. AI has become as much a marketing tool these days as anything, and the technology of machine learning has genuinely beneficial applications in research, such as in this 2023 press release I wrote about using it to analyze the progression of brain tumours

It's a goal of mine in 2025 to engage in more hands-on crafts and activities, reducing my time spent doom-scrolling. Looks like I'll need to pay a visit to the Button Factory! 😊

On the topic of Barbie, I wholeheartedly agree (though I know this isn't groundbreaking and aligns with the consensus) that films greatly benefit from thoughtful, realistic sets. While CGI is often more cost-effective, the care put into tangible, immersive environments can elevate the storytelling experience. I couldn't imagine Barbie relying heavily on CGI—it would have diminished the story's impact.

A wonderful read as always, Melodie!

Finally had time to read this. Loaded topic, but I agree with you for the most part. Though AI has valuable uses, it's robbing the world of human creativity and inspiration. Great research, too. I want to visit New Zealand.