Song of the Week: “Us for Them,” by Gungor - “We will not fight their wars / We will not fall in line / Cause if it's us or them / It's us for them”

During World War II, the French-Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas was a prisoner of war in a camp in Hanover, Germany. Every day, he and the other prisoners would head out to do hard labor in the surrounding forest, and every day they faced violence and dehumanization at the hands of their Nazi guards.

In his essay “The Name of a Dog, or Natural Rights,” Levinas describes how the guards, along with their wives and children, were actively and intentionally involved in a campaign of “social aggression”: they psychologically “stripped” the prisoners of their “human skin.” They refused to acknowledge “our sorrow and laughter, illnesses and distractions, the work of our hands and the anguish of our eyes” (153).

Only one creature Levinas encountered affirmed his humanity: a stray dog the prisoners named Bobby, who joyfully greeted them whenever he saw them. “He would appear at morning assembly and was waiting for us as we returned, jumping up and down and barking in delight,” Levinas recalls. “For him, there was no doubt that we were men” (153).1

Levinas’s experience during WWII - and the dehumanization and persecution he continually faced as a Jew - profoundly shaped his understanding of philosophy. For Levinas, philosophy was not a mere puzzle or abstract intellectual exercise: rather, it was a calling that must start from a foundation of ethics.

Central to Levinas’s ethics was the relationship between the “self” and the “other.” All of us, he argues, are trapped within our own consciousnesses. We see the world through our individual experiences, and struggle to believe that other people are as complex, as important, or as rich in their inner lives as we are. Still, he argues, we must always strive to see the “face” of the other - that is, to recognize their vulnerability and humanness, their simultaneous difference and sameness from us, and our own responsibility to care for them as much if not more than we care for ourselves.

“No one,” he writes, “can remain in himself: the humanity of man, subjectivity, is a responsibility for the other, an extreme vulnerability” (Collected Philosophical Papers 149).

In other words, the absolute ethical imperative - the thing that enables transcendence - is to love my neighbor as myself.

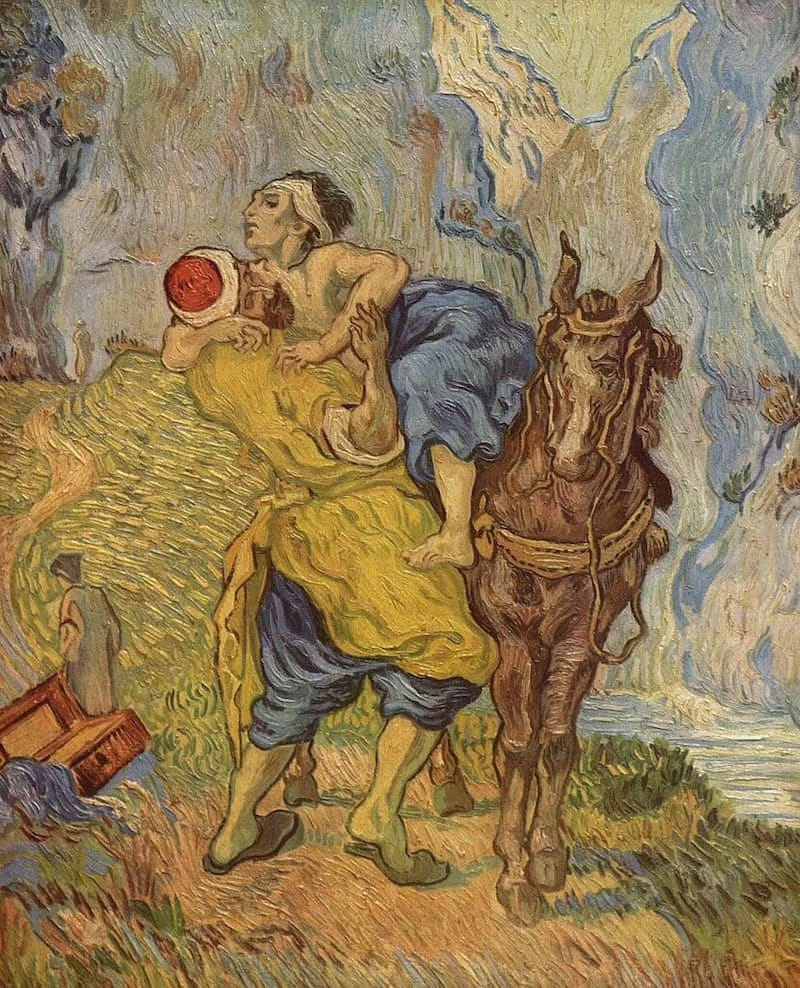

Samaritan

There is, perhaps, no more famous parable in Christianity than that of the Good Samaritan. Even people who have never opened a Bible are familiar with it, in part because of its ubiquity in modern culture. Taylor used to work as a security guard at Good Samaritan Hospital. Many states and countries have Good Samaritan laws on their books, protecting bystanders who intervene in an emergency situation.

The parable of the Good Samaritan is found in the Gospel of Luke, chapter 10. Jesus is in conversation with an expert on the law, who wants to test his theological orthodoxy. “Teacher,” he asks, “what must I do to inherit eternal life?”

Jesus answers his question with a question: what does it say in the law?

The teacher responds by quoting two verses from the Torah: “Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind” (Deuteronomy 6:5) and “Love your neighbor as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18).

“Do this and you will live,” Jesus affirms, but still the teacher presses on. “And who is my neighbor?” He is, perhaps, trying to catch Jesus in a moment of ignorance: in context, the larger passage says: ““‘Do not hate a fellow Israelite in your heart. Rebuke your neighbor frankly so you will not share in their guilt. ‘Do not seek revenge or bear a grudge against anyone among your people, but love your neighbor as yourself.” (Leviticus 19:17-18). The command to “love your neighbor” is part of a larger set of teachings about maintaining peaceful relations among the people of Israel: instructions for the governance of a homogenous community.

Jesus does not, however, reference this larger context. Instead - as he so often does - Jesus tells a story.

A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, when he was attacked by robbers. They stripped him of his clothes, beat him and went away, leaving him half dead. A priest happened to be going down the same road, and when he saw the man, he passed by on the other side. So too, a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. But a Samaritan, as he traveled, came where the man was; and when he saw him, he took pity on him. He went to him and bandaged his wounds, pouring on oil and wine. Then he put the man on his own donkey, brought him to an inn and took care of him. The next day he took out two denarii and gave them to the innkeeper. ‘Look after him,’ he said, ‘and when I return, I will reimburse you for any extra expense you may have.’ (Luke 10:30-35 NIV)

Jesus ends his story with another question for the teacher: “Which of these three do you think was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of robbers?”

The teacher seems uncomfortable - he doesn’t even want to say the word “Samaritan.” “The one who had mercy on him,” he finally admits.

As numerous Biblical scholars and theologians have noted, the story of the Good Samaritan has become so familiar - even archetypal to us - that we often miss its cultural specificity. Indeed, “Samaritan” has become the word we use to describe someone who selflessly takes care of a stranger.

That cultural specificity, however, would have been central to Jesus’s listeners. Samaritans and Jews, though both claiming descent from the Israelites, were distinct ethnic groups. They hated each other fiercely, and were involved in a long-running conflict: the Jews destroyed the Samaritans’ temple on nearby Mount Gerizim, and the Samaritans reciprocated by desecrating the Jewish temple at Passover with human bones only a few decades before Jesus’s ministry began.

Jesus draws a sharp contrast between the priest and the Levite - holy, powerful men who belong to the same ethnic and social group as the injured man - and the Samaritan: an obvious “other.” Yet the Samaritan is the one who overcomes fear and prejudice to take care of the injured man, simply because he is injured.

In “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” the last speech Martin Luther King Jr. gave before his assassination, King addresses an audience of Civil Rights activists in Memphis, Tennessee who are weary of violence and political persecution. “We’ve got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end,” he says.“We’ve got to see it through. And when we have our march, you need to be there. Be concerned about your brother. You may not be on strike. But either we go up together, or we go down together.” He is referring specifically to the Memphis Sanitation Strike, in which 1,300 Black sanitation workers went on strike demanding fair wages and humane working conditions.

In his call for solidarity, King retells the story of the Good Samaritan, referring to the Samaritan as “a man of another race.” King extends some empathy to the priest and Levite, noting that they were in a potentially dangerous situation, on a steep and winding road rife with danger. “The first question that the Levite asked was, ‘If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?’”

And yet, King says, the Samaritan stopped - compelled by the wounded face of the other. “And he reversed the question: ‘If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?”

“That’s the question before you tonight,” he concludes. “Not, ‘If I stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to all of the hours that I usually spend in my office every day and every week as a pastor?’ The question is not, “If I stop to help this man in need, what will happen to me?’ ‘If I do not stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to them?’ That is the question.”

If I do not help, what will happen?

The Cruelty Is the Point

It has been almost impossible, in the last month, to keep track of all the cruelties, all the flagrant violations of the law, that have been inflicted by Donald Trump and his cronies.

This is intentional: as political commentator Ezra Klein observes, the overwhelming avalanche of evil being gleefully enacted by this administration is part of a “flood the zone” strategy designed to overwhelm people and leave them numb and frozen with fear and horror. Or, as The Atlantic’s Adam Serwer succinctly noted in 2018, during Trump’s first term: “the cruelty is the point.”

Vital climate science and medical research is being defunded. Trans people are being stripped of protections. ICE is raiding elementary schools. Everywhere you look, our neighbors are wounded and bleeding.

I am continually sickened by this administration’s actions, but I am not surprised. As Stephen Colbert said in a recent interview with fellow comedian John Oliver, “It’s exactly what you thought, but worse than you could have imagined.”

And yet. And yet. There are always new depths to sink to, novel cruelties, fresh horrors every day. But the one that has really stayed with me is the attack on USAID.

On the day of his inauguration, Trump signed an executive order triggering a funding freeze and putting USAID staff on leave. USAID, whose $71.9 billion annual budget represents only around 1% of federal government spending, is responsible for more than 40% of the world’s humanitarian aid. Directly and through partnerships with non-profit and non-government organizations around the world, USAID is a vital part of the global work to treat and eventually eradicate horrific diseases including tuberculosis, polio, and HIV/AIDS. The agency also intervenes after natural disasters and in the aftermath of wars, including wars waged by the United States in the past.

One example? Since the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, more than 71,000 innocent people in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos have been killed by unexploded munitions left by the United States. An additional 150,000 people have been maimed, many of them small children innocently playing with landmines or grenades. As part of the United States’s attempt to make restitution for this enduring violence, USAID funds clean-up efforts and medical care and rehabilitation for those injured by unexploded munitions. Or at least, it did. Now, people are unable to access desperately needed resources around the world.

As John Green explains in a recent video, for example, vital tuberculosis medications that have already been paid for are rotting in warehouses because USAID workers are not allowed to distribute them to the patients who desperately need them. This is a humanitarian crisis in itself, but it is also extremely short-sighted on a global scale. Tuberculosis is an unusually resilient bacteria, requiring months of daily antibiotics to destroy. By pausing treatment even for a few days, the Trump administration is directly causing the evolution of drug-resistant strains of tuberculosis: strains that could travel around the world, impervious to existing medicine.2

There are other mercenary reasons to support the funding of USAIDS as well. Widespread disease and suffering from natural disasters lead to global instability; it is in the United States’s foreign policy interests to increase global stability.

But putting all that aside, for a moment, what horrifies me the most - what keeps me awake at night - is that the people who have unleashed this literal plague of suffering upon the most vulnerable and powerless people in the world claim to do so in the name of Jesus.

Christian Love

I am a scholar of right wing Christianity in the United States. I know that Christian nationalism is a political and cultural ideology more than a theological one. I know that 78% of white evangelicals voted for Trump because he promised them patriarchy, white supremacy, and revenge against their perceived enemies.

And yet it still destabilizes me to watch them baptize Trump’s evil in the name of Christ.

In a Fox News interview in January, vice president and Catholic convert J. D. Vance argued that the administration’s policies and priorities stemmed from the Christian theology of ordo amoris, or the “order of love.” “There is…” he said, “a very Christian concept that you love your family, and then you love your neighbor, and then you love your community, and then you love your fellow citizens in your own country, and after that, you can focus and prioritize the rest of the world.”

In an open letter to American bishops last week that did not directly name Vance, Pope Francis rebuked his interpretation of Christian love, particularly as it relates to immigrants and refugees. In words that recall Levinas’s philosophy of the other, Pope Francis writes:

Christians know very well that it is only by affirming the infinite dignity of all that our own identity as persons and as communities reaches its maturity. Christian love is not a concentric expansion of interests that little by little extend to other persons and groups. In other words: The human person is not a mere individual, relatively expansive, with some philanthropic feelings! The human person is a subject with dignity who, through the constitutive relationship with all, especially with the poorest, can gradually mature in his identity and vocation…The true ordo amoris that must be promoted is that which we discover by meditating constantly on the parable of the ‘Good Samaritan,’ that is, by meditating on the love that builds a fraternity open to all, without exception.

In other words: who is my neighbor?

Whoever needs my help.

When it comes to “Who is my neighbor?” what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

Despite his gratitude towards Bobby, Levinas resisted any philosophical categorization of animals as thinking or loving beings, nor did they allow them a “face.” Jacques Derridas explores this further in his punishingly dense book The Animal That Therefore I Am (2002).

By some estimates, tuberculosis has killed 1 out of 5 humans in all of history. It still kills more than one million people every year, mainly in Africa and Southeast Asia, but in the West we have relegated it to the history books because it kills very few people in North America anymore

Couldn’t agree more! We’ve got to do everything possible to stem Trump’s tide of self-serving demagoguery.