Song of the Week: “Jesus from Texas,” by Semler - “My mom turned eighteen in the 1960s and she doesn’t remember Stonewall”

There’s a dramatic graph that started circulating on social media a few years ago. Perhaps you’ve seen it. On the y-axis, a series of percentages. On the x-axis, a series of dates, stretching from 1880 to 2000. Between 1890 and 1960, the line on the graph climbs from 6% to 12%, where it then holds steady indefinitely.

This graph, based on survey data reported in “The History and Geography of Human Handedness” (2009), measures the reported rate of left-handedness among Americans by birth year.

During the Victorian era, left-handedness was seen as a moral defect, something that must be trained out of children as early as possible. Left-handedness was associated with dishonesty, laziness, and unintelligence, and children were often beaten or otherwise disciplined if they did not use their right hand. Even my father, who was born in 1960, remembers being forced to write with his right hand at school when he was a small child. Gradually, however, this practice became less popular, and the true prevalence of left-handedness in the population emerged and held steady at 12%.

In other words: it was impossible to tell how many people were truly left-handed until it was safe to be left-handed.

Here’s another graph with some steadily increasing numbers - numbers that some might say are the result of recent trends, or jumping on a bandwagon, or the decline of society.

This graph, of course, measures the percentage of Americans each year who identify as LGBTQ.1

Sometimes Stories Are Destroyed

One of my favorite books of all time is Carmen Maria Machado’s experimental memoir In the Dream House. Machado narrates the thrills and horrors of her relationship with her emotionally and physically abusive ex-girlfriend, all filtered through a kaleidoscope of different genres. Each short chapter is written in a different style: “Dream House as Movie Musical,” “Dream House as Film Noir,” “Dream House as Sci-Fi Thriller,” and so on.

Most memorably, in “Dream House as Choose-Your-Own-Adventure,” Machado temporarily transforms the book into an old-school text adventure in which the reader attempts to wake up and make breakfast without angering her girlfriend. The task is impossible, however, and no matter what the reader does, the action loops into another day of abuse.

I first taught In the Dream House as the beginning text in a university class about genre; the bite-sized chapters and dramatic subject were an ideal way to get my students thinking and talking about different genres. During our discussion of the book, however, we also spent a lot of time talking about archives.

At the beginning of the book, in “Dream House as Prologue,” Machado introduces Saidiya Hartman’s concept of the “violence of the archive.” “This concept,” Machado writes, “- also called ‘archival silence’ - illustrates a difficult truth: sometimes stories are destroyed, and sometimes they are never uttered in the first place; either way something very large is irrevocably missing from our collective histories.”

Archives, Machado reflects, whether they are the literal archives found in libraries and museums, or the cultural collections of stories we repeat in our homes and our classrooms, are wrapped up with power. “What is placed in or left out of the archive is a political act, dictated by the archivist and the political context in which she lives…Sometimes the proof is never committed to the archive - it is not considered important enough to record, or if it is, not important enough to preserve. Sometimes there is a deliberate act of destruction…” (4).

While the violence of the archive affects many groups of people - enslaved people and undocumented immigrants, the mentally ill and the unruly, the illiterate and the very poor - Machado is particularly interested in the ways that queer people are forgotten by or erased from history. As a woman in a queer abusive relationship, she had even less examples to turn to in history - but that lack of history did not make her situation any less real, or any less dire.

In the Dream House, then, is partly Machado’s attempt to create the archive that she lacked: to document overlooked examples of abusive queer relationships, and to write her story into as many forms as possible so that it might be legible to others who can benefit from it.

She is also interested, however, in the larger question of our collective responsibility, as memory-keepers and story-tellers, to those who come before us, who haunt our official histories: “How do we move toward wholeness?” she muses. “How do we do right by the wronged people of the past without physical evidence of their suffering? How do we direct our record keeping toward justice?”

Encrypted

I have already cautioned many times in these pages about the difficulty of projecting our modern narratives onto history. In my own lifetime alone I have seen the terminology surrounding ability and race and gender identity and sexual orientation shift several times, and I know that it would be a fool’s errand to try and assign precise labels to people in history, like attempting to affix butterflies to cardboard with a pin.

At the same time, however, it is just as revisionist to claim that queer and trans people are a modern phenomenon, a symptom of societal decline or modern fads. Throughout human history, and across multiple cultures, there has been gender and sexual diversity. Many Indigenous cultures around the world understand gender outside of a male-female gender binary. Even within binary gender cultures, we have examples of “gender outlaws” like the Ancient Egyptian Hatshepsut, who was assigned female at birth but wore a false beard and referred to herself as “King,” or the Public Universal Friend, a Quaker who claimed to have died of illness and been resurrected by God as genderless.

Historians have speculated about the potential queerness of everyone from Alexander the Great to William Shakespeare to Lewis & Clark, but those speculations are always limited both by changing cultural norms and by the historical impulse to burn records containing scandalous information. Sometimes, however, we get lucky, and those scandalous records - though temporarily hidden - endure long enough to be recovered.

Anne Lister was an aristocratic English woman who lived from 1791-1840. Like many women of the era, she kept an almost daily journal, documenting her walks, meals, social calls, and purchases. Unlike her peers, however, Lister also wrote extensively in a self-devised code she called her “crypthand”: a script that draws heavily on both mathematics and Ancient Greek.

Whenever she finished a notebook, she would hide it behind a wall panel in her ancestral home, Shibden Hall. When Lister died unexpectedly at the age of forty-nine while traveling in Russia, her journals were left behind.2

In 1887, her last remaining relative, John Lister, found Anne’s journals and decided to publish some of the plain English sections in the local newspaper, as charming accounts of life in the village fifty years earlier. He and his friend Arthur Burrell, a teacher and local history buff, were intrigued by Anne’s code, and decided to try to crack it. What they discovered shocked and horrified them so much that Burrell wanted to burn the diaries; John, however, balked at destroying historical records, and instead returned them to their hiding place in the wall, where they remained until John died in 1933.

After John’s death, Shibden Hall became a museum, and Anne Lister’s journals entered the local archives along with all of the other family documents. Also included in those documents was John Lister and Arthur Burrell’s key to Anne’s code. The diaries remained untranslated, however, for fifty years - until recent PhD graduate Helena Whitbread came across them in her local archives and decided to translate the substantial coded sections of the five million word diaries.

There, she discovered the terrible secret that had so horrified Arthur Burrell and John Lister: Anne Lister was a lesbian - and a highly sexually active one, at that.3

In the crypthand passages, Lister writes about her masculine tastes and manners, her self-image, and her feelings for and sexual encounters with other women in vivid detail. “I felt that my happiness depended on having some female companion whom I could love & depend upon…” she writes on July 11, 1817. Anne Lister was particularly devastated by the perceived betrayal of her lover Marianne, who promised to love only her but then married a man (though this marriage did not prevent repeated sexual trysts in the years that followed).

Though Marianne proved unfaithful, Lister’s devotion to her - and understanding of her own identity as a woman who loved other women - remains consistent. “I love and only love the fairer sex and thus, beloved by them in turn, my heart revolts from any other love than theirs,” she writes on January 29, 1821.

Lister, of course, was not a perfect figure; as Whitbread remarks in the introduction, she was also a snobbish aristocrat, judgmental, and cruel, obsessed with money and disdainful towards many of her female lovers. She was not a perfect angel or a blameless martyr.

Rather, we remember and celebrate Lister today because of her importance to the archive.4 Through her diaries, Anne Lister emerges as a three-dimensional character: petty, grumpy, vulnerable, stubborn - and undeniably queer.

Memory-keeping

Much closer to home, this week I had the opportunity to tour the University of Waterloo archives, and see some of the queer history housed in our collection.5

The Waterloo university library began forty-eight years ago specifically as a women’s studies archive, and still contains important documents and ephemera from the Canadian women’s suffrage movement and the reproductive rights movement. In the 1990s, the collection expanded to document queer and trans activism and culture both in the Kitchener-Waterloo region and around the world.

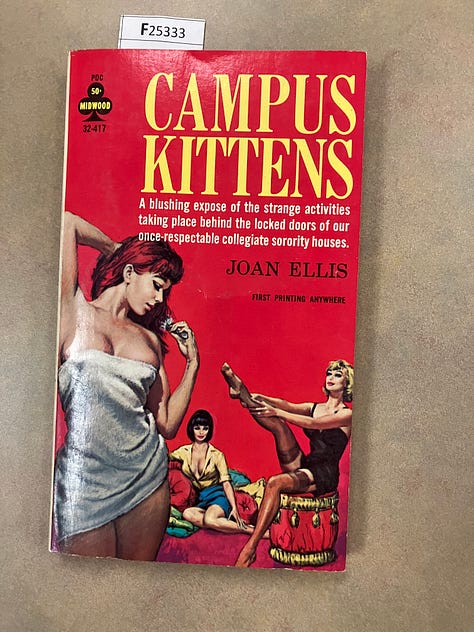

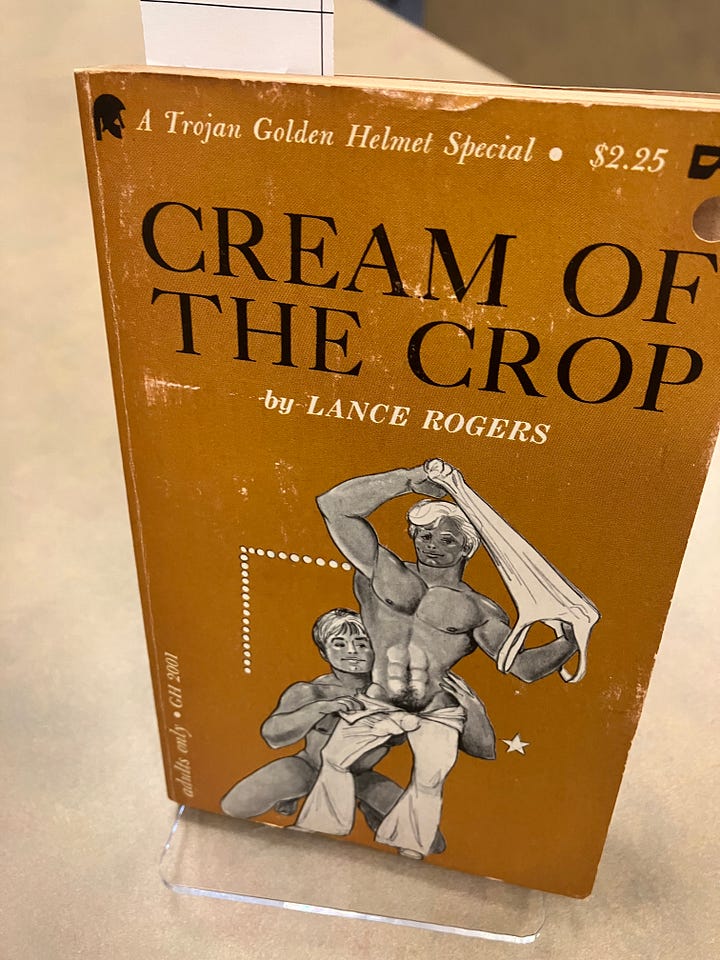

Some of the items in the collection seem laughable now, such as these 1950s and 1960s pulp novels with titles like Odd Girl Out and Campus Kittens.

With their sensual cover art and salacious descriptions, these pulp novels - especially the ones about women - were created more to appeal to straight men than for queer consumers. Nevertheless, the librarians explained, for many queer people in the 1950s and 1960s, such texts - fetishizing as they were - still served as important touchstones, reassuring them that they weren’t the only people to have these feelings.

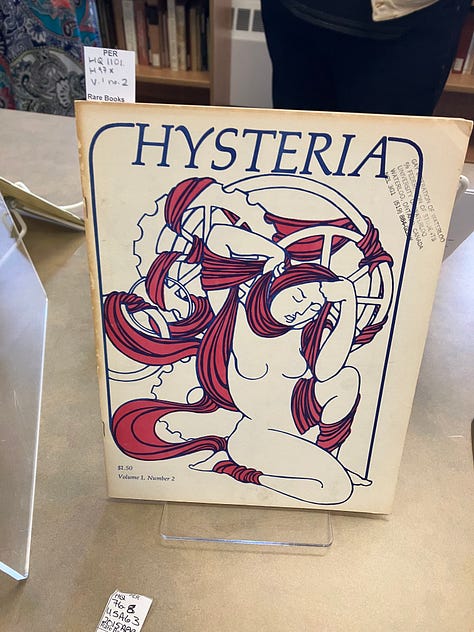

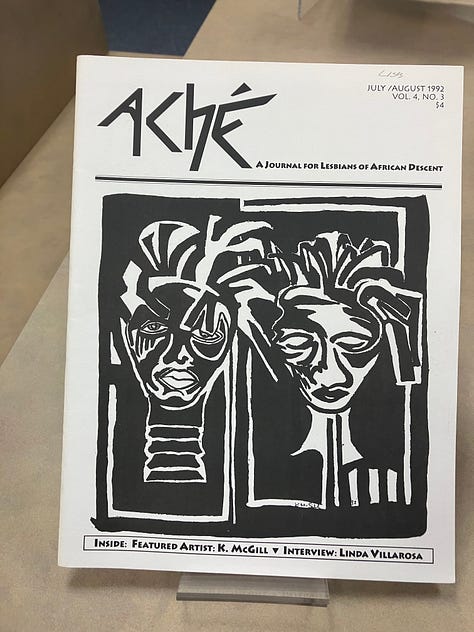

More resonant were the indie publications from throughout the twentieth century, which included the 1960s Turnabout: A Magazine of Transvestism; the 1980s Hysteria: A Feminist Magazine by Women in Kitchener-Waterloo, and the 1990s Aché: A Journal for Lesbians of African Descent.

As I flipped carefully through articles about how to handle being stopped by police, calls for equal pay for equal work, and lists of safe hotels and restaurants to visit while traveling, I was reminded of the importance of reminding, amongst temporarily-rainbow corporate logos and Scotiabank Pride floats, that the first pride was a riot. I was reminded of how easy it is to take for granted the freedom I have to exist openly as a bisexual woman - and how recently that was not the case.

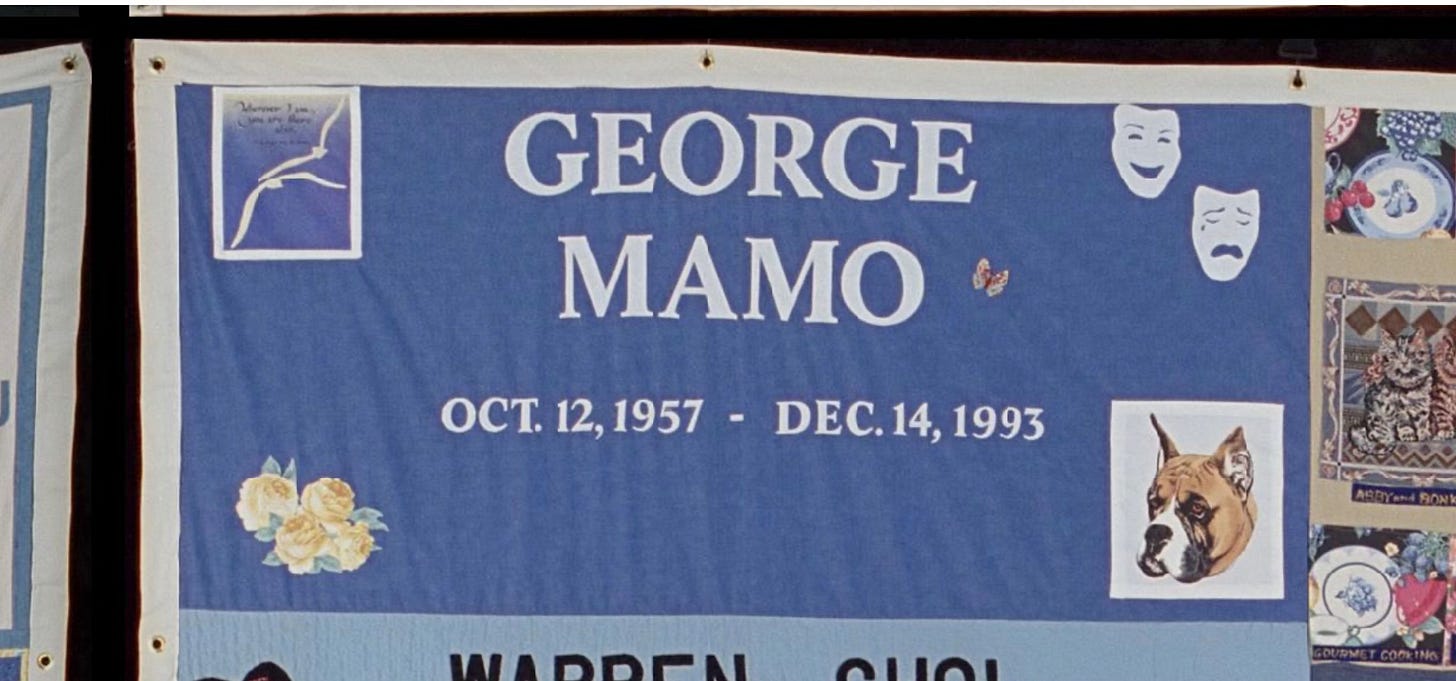

I was reminded of the 50,000 panel AIDS Memorial Quilt, the largest piece of folk art in the world, dedicated to commemorating almost 110,000 people lost to AIDS since the 1980s. In the early days of the AIDS epidemic, the disease was so stigmatized that families would not visit their children as they died, nor even receive their bodies after death. Many churches, funeral homes, and cemeteries refused to allow funerals or memorials for AIDS victims, and so their loved ones had nowhere to commemorate them - except by creating a square on the quilt.

Though it has not been displayed in its entirety since 1996, people are still adding panels to the quilt. You can view the entire thing online, and zoom in to view individual squares.

The scale of it is overwhelming, even on a laptop screen. I zoomed in at random, and read the square for George Mamo. Plain blue with white writing: born October 12, 1957, died December 14, 1993. He was thirty-six.

Unlike some of the squares covered in embroidery, sequins, or other elaborate designs, there are only a few clues as to who George was: a patch with indecipherable writing, comedy and tragedy masks, yellow roses, a butterfly. And a picture of his dog.

History, huh?

In the same class on genre where I began with Machado’s In the Dream House, I ended with Casey McQuiston’s romance novel Red, White, and Royal Blue (2019). The novel (which was recently adapted into an unfortunately mediocre movie for Prime), is set in an alternate timeline where the Texas-born Ellen Claremont became the first female president in 2016. The protagonist, her son Alex, realizes he is bisexual when he goes from enemies to friends to falling in love with Henry, the grandson of the Queen of England.6

While the novel is funny, sexy, and a rollicking good time all around, one of the things that sets it apart are the emails that Alex and Henry exchange during their secret romance. They begin a tradition of quoting letters from historical figures to each other at the end of each email. For example: “Vita Sackville-West to Virginia Woolf–1927: With me it is quite stark: I miss you even more than I could have believed; and I was prepared to miss you a good deal.”

Alex and Henry are keenly aware of the often-forgotten archive of queer stories who come before them: the stories of people who legitimize their love for each other even as they compel them to create a safer and more just world. “Thinking about history makes me wonder how I’ll fit into it one day, I guess,” Alex muses. “And you too. I kinda wish people still wrote like that. History, huh? Bet we could make some” (241).

Alex and Henry, of course, are fictional characters in a romance novel, not real queer figures in modern politics. Yet that fiction is itself a kind of political imagination - one firmly rooted in a very real archive. As Cat Sebastian writes in her wonderful essay “Romance, Compassion, and Inclusivity (Or: How Romance Will Save the World)”:

Romance is the only genre that demands a happy ending. It structures the entire story around that demand and takes the reader along with it. This isn’t just empathy, it is a restructuring of the way people might think of other human beings - who deserves and should expect happiness, who can be loved. There are no other books that insist on joy and love as an end in itself. This is nothing less than radical (7).

Every day, in our homes, schools, libraries, and public spaces, we make choices about the stories we remember, and the ones we try to suppress. We can look to the past as a warning and an encouragement to do better, or we can try to hide the stories that make us uncomfortable behind the walls. When people ban books, or pass bathroom bills, or insist upon a homogenous and false narrative of the past, all they are doing is making the world crueller and more dangerous. They are hiding stories that could save a child from self-harm, a teenager from suicide, an adult from abuse.

But they cannot, no matter how hard they try, completely erase the testimony of the archive: that, like plants pushing their way through cracks in the pavement, queer people stubbornly endure.

We have always been here. And we always will be.

When it comes to the violence of the archive, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

This second graph is taken from Statista, based on Gallup data. The years 2018 and 2019 are missing because Gallup did not collect data on this topic those years.

Lister never married, and her brothers both died before reaching the age of twenty. As a result, Lister had an unusual amount of financial and social independence for a woman of the time period. When she died, her estate passed to her paternal cousins.

No doubt part of John’s anxiety around the journals stemmed from his own secret homosexuality, and concerns that people would connect him to his queer ancestor.

Lister’s journals were recently adapted in the HBO show Gentleman Jack (2019-2022)

This opportunity, like so many other wonderful experiences I have had in the year, was thanks to our fantastic event coordinator, Fiona. She also organized the monthly queer film series I wrote about last week. The first film in that series was The Celluloid Closet (1995), an excellent documentary about queerness in the first one hundred years of Hollywood filmmaking.

His grandmother is named Queen Mary, suggesting a bit of alternate history as well in regards to the House of Windsor.