Song of the Week: “Don’t Carry It All,” by The Decemberists - “And you must bear your neighbor’s burden within reason.”

The other night, I had a dream where I fell asleep watching a movie, and then I took a several hour nap. Inside of the dream.

Do you know how psychologically exhausted you have to be to already be asleep and then think, “hmm, I could use a nap”?1

With hiring freezes, layoffs, and attacks on free speech threatening higher ed, morale is low at work. I recently joined the board of a non-profit, and have been putting in hours of work each week addressing personnel struggles and helping them comply with government regulations. Cost of living is absurdly high, the job market is bad, and idiotic tariffs threaten to blow up the global economy. There are taxes to file, deadlines to meet, and a never ending stack of dishes to do. I only get to see Taylor two days a week, and he’s perpetually exhausted from traveling non-stop for work. And on top of all of that, it keeps snowing - in April - so every time I step outside my entire body clenches like a fist.

And then, of course, there are what Taylor and I have begun to refer to simply as “The Horrors”: the Trump administration’s collection of crimes against humanity, assaults on democracy, and exhibits of sheer stupidity and pointless cruelty that are designed to leave us feeling helpless, terrified, and without hope.

I don’t know how to describe it all, except to call it a heaviness. A heaviness that I carry everywhere, and can never remove.

When I was in grad school, my best friend Jillian and I went on a two week backpacking trip through the UK. Everything for the trip - clothes, towel, notebooks, souvenirs - was crammed into a bright red 46 liter Osprey pack that I carried on my back.

One evening, we arrived in the tiny town of Stratford-upon-Avon, and discovered that bus service ceased entirely at 7 pm. There were no taxis or Ubers. The only way to get to our hostel - located almost two miles outside of town - was to walk.

It was early January, and a steady, ice-cold rain was falling. It was too dark to see the mud that clung to my boots, but I felt it with every squelching step. My feet were covered in blisters. I had a headache. And above everything else, my whole body ached from that pack: the straps digging into my shoulders and chest and hips, the way something hard-edged poked me every time I adjusted it, the sheer weight of it compressing my spine. I fantasized, as we walked, about taking the whole thing off and hurling it into the Avon River. I wondered if we would ever find our hostel in the dark, or if we would just walk forever.

Eventually, of course, we did reach our hostel, where there was tea, and hot showers, and a kind welcome. In the following days we got better at checking timetables ahead of time, and our backs grew stronger. Now, that miserable night is just another story to tell fondly from the comfort of our homes.

But these days, more often than not, I feel like I am back there, soaked to the skin, carrying my whole life on my back. There’s no promise of hot showers and a lifted load just around the bend. Yet I trudge on.

More Weight

All week, I’ve found myself looking for metaphors to explain what it feels like. I’m not suicidal or clinically depressed. I have not given up hope. So much of the weight I carry is a heaviness born of love: love for friends who are trapped in bad relationships or struggling with chronic illness, love for people and organizations who are fighting to make the world a better place. But there is just so much of it. And yet I feel like it is always my responsibility to take on more.

There’s this scene from Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible, about the Salem Witch Trials, that I think about a lot. A farmer, Giles Corey, has been accused of witchcraft, but he refuses to confess. If he confesses, his accusers will seize his valuable property, which will otherwise go to his children upon his death. For three days they torture him: he lies naked on a dungeon floor while they pile rocks on a board placed across his body. Three times, they demand he confess, and three times he defiantly replies “more weight.”

Corey, of course, is crushed to death.

On Tuesday, an unexpected and urgent request left me feeling so overwhelmed that I couldn’t function. Unsure what else to do, I googled “I am overwhelmed,” and read an article by Emine Saner, accompanied by this great illustration by Allan Sanders that accurately demonstrates what it looks like inside my brain.

Saner quotes clinical psychologist Linda Blair:

“We are constantly introduced to challenges, threats, whatever you want to call it, in multiple areas of our life. We’re receiving information in the news that makes us anxious, but we can’t do anything about it. We’re monitoring our kids a huge amount more than we used to. We feel obliged to answer emails much more quickly than we ever felt obliged to answer post. It’s not that there’s any one thing that we’re being asked to do … it’s that there are multiple demands on our attention, with the extra pressure of our brains being taught to be distractible [by devices and algorithms], that’s making people get overwhelmed…We cannot do more than one thing at a time and yet we’re being asked to.”

Saner recommends limiting screen time, practicing better time management, and establishing firm priorities: all of which I’ve already been trying to do, with some success. But she also admits that such solutions can only take us so far. We have to rest and relax, she concludes.

Easier said than done.

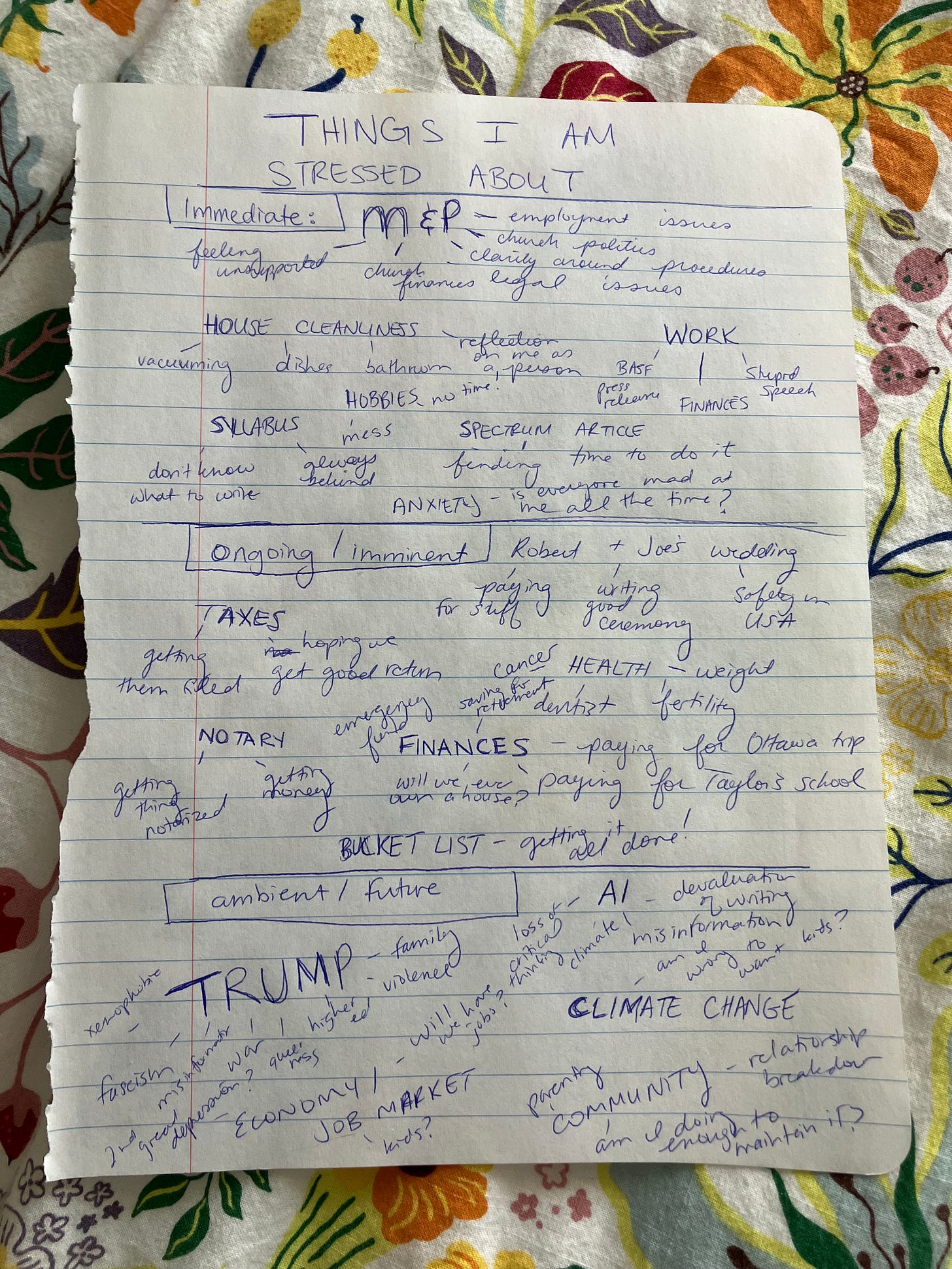

Another article offered a simpler and more immediate instruction: write it all down.

So I did. Within five minutes I had filled an entire page.

It felt a little bit like taking that backpack off for a moment and inventorying the contents. I couldn’t get rid of most things, but at least I felt validated in my exhaustion. I really have been carrying a lot.

Invisible Loads

While all of us have a lot to carry these days, some of us will always carry more than others.

People of color carry the relentless weight of systemic racism and surveillance, terribly exacerbated these days by the brash and unapologetic white supremacy of those in power. People with disabilities face both visible and invisible barriers to access that make everything from going out to eat to navigating public transit physically and emotionally exhausting. People who were neglected or abused must learn to love themselves and others while fighting against patterns of trauma and dysfunction that disadvantaged them from the beginning. And the list goes on, and on, and on.

There have been a lot of conversations, recently, about women’s “invisible loads” within their families: the way they manage not only errands, childcare, and careers, but also the planning and caring that keeps so much of the world spinning. We schedule doctor’s appointments, send birthday cards, drop casseroles off for sick friends, and make holiday magic. Some of it is rewarding: I love baking special birthday desserts for members of my family, or spending hours helping a friend talk through a relationship dilemma. But all of it takes time, and energy, and labor.

Too often, no one notices all the things that we’re doing. They only notice when we fail.

In a 2019 study, sociologist Allison Daminger surveyed 35 heterosexual couples and discovered that, even in couples that sought to be egalitarian, women still did “the lion’s share.” As the BBC’s Melissa Hogenboom reports:

Daminger identified four clear stages of mental work related to household responsibilities: anticipating needs, identifying options, deciding among the options and then monitoring the results. Mothers did more in all four stages, her research showed; while parents often made decisions together, mothers did more of the anticipation, planning and research. In other words, fathers were informed when it came to decisions, but mothers put in the legwork around them.

Even when they recognize it’s unfair, women often continue to do this work: because getting their partners to do it is more emotionally exhausting than doing it themselves, and the consequences if things fall apart will be harsher for them. There is still, Daminger says, “this sense that women are ultimately responsible for family outcomes. There are more costs to a woman if these things don’t go well or don’t happen.”

There are important things we all must do, on personal and systemic levels, to make the division of labor more fair. Those things take time, and personal sacrifice, and often they are complex problems with multi-pronged solutions.

But the first step, I think, is acknowledging what others are carrying - and recognizing the strength it takes to carry on.

I love this poem, “Women Holding Things,” by Maira Kalman.

“Sometimes, when I am feeling particularly happy and content,” she muses, “I think I can provide sustenance for legions of human beings. I can hold the entire world in my arms. Other times, I can barely cross the room, and I drop my arms, frozen. There is never an end to holding.”

Superheroes

“I feel like Spider-Man,” I told Taylor the other day. “I’ve been given a lot of power, and privilege, and ability, and with that comes the responsibility to do whatever I can to help.”

The comparison was apt, of course, not simply because of Spider-Man’s abilities, but because of how stretched thin he frequently is. In Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man 2, Peter Parker tries to juggle working and being a student with the relentless cries for help of a city that is never at peace. There is never enough time, and never enough money, and his relationships begin to fray at the edges. Finally, near the end of the movie, he reaches his limits: he stops a runaway subway train from crashing by pushing his body to its breaking point, and collapses unconscious as soon as the people are safe.

The people on the train carry his body over their heads and gently lay him on the floor to rest. “He’s just a kid,” one man says, shaking his head. “No older than my son.” They promise to protect his secret identity, and together, they help him get up.

A couple of years ago, at a terribly low point, when things felt even more overwhelming than they do right now, I occasionally daydreamed about being diagnosed with cancer, or horribly breaking a bone. It’s not that I wanted to be hurt. It’s that I wanted an undeniable justification to rest without feeling guilty. I wanted to stop for a while and let everyone else carry me.

After the election, when things felt so dark that I had trouble getting out of bed, I finally relented and started going to therapy. I had been to therapy briefly before, when I started having panic attacks about my dissertation back in 2018. The overburdened university therapist let me cry for a while, gave me some worksheets, and then after a few sessions said that I seemed to have things under control and sent me on my way.

“I don’t need to go to therapy,” I kept telling Taylor in the intervening years. “I already know all the things they’ll say are wrong with me.”

But finally, I agreed to go anyway.2 And something happened that I didn’t expect. My therapist didn’t tell me about my flaws. She told me I was good. She told me I was kind. She told me that I was doing enough.

A few months ago, I told her about all of the things that had been bearing down on me: family relationships and the job market, fascism and climate change.

“That sounds like a lot,” she said gently. “Why do you think it’s your job to fix all of it?”

Walking On

Last summer, Taylor and I went to see Inside Out 2, the sequel to Pixar’s incredible movie about adolescence and emotional complexity. In the first film, a tween girl named Riley has five anthropomorphized emotions that run her life: Joy, Sadness, Fear, Anger, and Disgust. In the sequel - as Riley goes through puberty and attends a high-pressure hockey training weekend - she gains four new emotions: Embarrassment, Envy, Ennui, and Anxiety.

Throughout the weekend, as Riley navigates complicated relationships and worries about how she’ll fare in high school, Anxiety grabs the controls again and again. Anxiety takes over Riley’s imagination, forcing dozens of workers to draw scenarios of all the ways things could go wrong. And, in the film’s climax, she begins to move so frantically and so fast that she creates a vortex of destruction, and triggers a panic attack in Riley.

“I’m sorry,” Anxiety gasps. “I was just trying to protect her.”

Ultimately, Riley reconciles with her friends. They find ways to support each other. And the emotions learn to direct Anxiety towards the things she can help with - like studying for a Spanish test - instead of letting her run the entire show.

I wish I could tell you that I have figured out a way to make my burden lighter, but I haven’t. What I have found are things that give me the strength to keep trudging along. It’s easy to forget, when I remember that long dark walk carrying my pack, that Jillian was walking along next to me carrying a load of her own. We kept each other going.

The same night that I felt frozen in place, my friend Betta came over for dinner, and we sat on the couch and talked and laughed and watched TV. Later in the week, despite being busy, I went to my knitting circle and spent two hours chatting about motherhood and working on a soft, vibrantly pink scarf. This Monday I have therapy.

I delegated some of the tasks on my to-do list. I vacuumed my apartment. I drank water. I walked on.

And today, as I waited for the bus to work, despite the persistent chill, the sun was warm on my face.

Instructions on Not Giving Up, by Ada Limón More than the fuchsia funnels breaking out of the crabapple tree, more than the neighbor's almost obscene display of cherry limbs shoving their cotton candy-colored blossoms to the slate sky of Spring rains, it's the greening of the trees that really gets to me. When all the shock of white and taffy, the world's baubles and trinkets, leave the pavement strewn with the confetti of aftermath, the leaves come. Patient, plodding, a green skin growing over whatever winter did to us, a return to the strange idea of continuous living despite the mess of us, the hurt, the empty. Fine then, I'll take it, the tree seems to say, a new slick leaf unfurling like a fist to an open palm, I'll take it all.

When it comes to the things we carry, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

I don't even like naps, which always leave me disoriented and moody. As a friend once quipped, they feel like macrodosing death.

Therapy is, unfortunately, not available to everyone, and prohibitively expensive without insurance. I’m very lucky that my work benefits include mental health coverage.

Resonates. Listen to that therapist. Sounds like some solid interaction is happening. And here’s a virtual 🤗!

One night not long ago my 9 year old granddaughter cried out in frustration, “l can’t go to sleep until I’ve solved all the world’s problems!” It starts young! It sounds to me like you guys could use some time at a beautiful and relaxing location on a scenic island. Just say the word.