Song of the Week: “Never Let It Die,” by Watsky - “I know that it’s tough / but it’s gotta be somebody, so then why not you?”

One of my favorite mugs is a small purple one with a roomy handle and a 90s-style airbrushed blue and green heart in the middle. “Heal the world,” it says on one side in looping yellow script. On the other: “Cook dinner tonight.”

This mug, which I tacked on to an order at the last minute to get to free shipping, is from Penzeys Spices, a remarkably unpretentious midwestern spice company known for their tasty seasoning blends, cheerfully unfussy design, and progressive politics.

If you haven’t already had the good fortune to buy or be gifted a box of Penzeys Spices, then perhaps you remember them from their support of the George Floyd protests in 2020. In response to accusations that they wouldn’t be so supportive of protestors if one of their own stores got looted, CEO Bill Penzey announced that the company would be “looting” its own Kenosha location and donating its entire inventory to food banks and community aid organizations.

I learned about Penzeys, however, from Kelly O’Connor McNees’s wonderful 2016 essay for the tragically defunct website The Toast. In “Hope for the Stricken: The Penzeys Spices Catalog,” McNees addresses an audience that she suspects is as burned out and disillusioned as she is by the constant onslaught of cruelty, suffering, and injustice that she sees in the world around her. “When you’ve written to your representative and carved some money from the grocery budget for UNICEF, but your heart still feels like one big bruise, where’s a soul to turn for respite?” she asks.

She suggests the Penzeys Spices catalog, with its spices, family recipes, and sincere editorials about labor organizing and environmental degradation, as a source of warmth and hope:

The home cooks who submit their recipes to Penzeys don’t do it just to show off (or, in the case of taco popcorn, surprise those of us who had assumed popcorn could not taste like tacos.) They want their signature dishes archived somehow in humanity’s big book, and they want the stories behind the recipes preserved too. Drew Doll’s chili recipe came down from his grandfather and father, both firemen who could be counted on to cook it for their firehouse crew. Leo Bassetto makes his apple pie with apples from his own backyard. Isn’t it wonderful to think of him out there picking them in the late September gloaming?

A few paragraphs later, she concludes:

“We’re doing what we can, sort of. I mean, probably not enough, but we are so seriously bummed. We are also hungry. And here is a slim volume representing the best of humanity - family, love, bravery, sacrifice, common sense, and food - to talk us down from the ledge.”

Where do we start, in the overwhelming work of healing the world? Penzey’s answers: with the ordinary.

Paradox

Tomorrow at 12:30 (ET), I am giving a talk over Zoom about the writing of Madeleine L’Engle (the details are here, if you’d like to join us!). As part of my preparation this week, I revisited A Wrinkle in Time (1962): winner of the Newbery Medal, L’Engle’s most famous work, and my favorite children’s book of all time.

If you aren’t familiar, A Wrinkle in Time is the story of how an awkward pre-teen girl named Meg, accompanied by her next door neighbor, her little brother, and three mysterious witch-like figures (Mrs Whatsit, Mrs Who, and Mrs Which), travels through space and time to rescue her missing scientist father from the forces of evil. It is a spectacularly weird and deeply specific novel, full of advanced mathematics, Shakespeare, Biblical allusions, faceless aliens, and the power of unconditional love.

The reason A Wrinkle in Time works, however, is its defiantly imperfect, stubborn, angry heroine Meg: a young girl whose frustration at the injustice of the world around her is matched only by her fierce love for her family and friends. In the 1960s, even more so than now, young girls were expected to be likable, sweet, and agreeable, and yet Mrs Whatsit urges “Stay angry, little Meg…You will need all your anger now” (92).

L’Engle wrote of the novel in her journal that it was “my psalm of praise to life, my stand for life against death.” A Wrinkle in Time was rejected by 26 publishers, and understandably so - it is a deeply unusual novel that defies easy categorization or marketing.

Despite the fact that L’Engle was an Episcopalian who characterized the book as her attempt to describe her theology of suffering and evil, A Wrinkle in Time has frequently been condemned by Christians for its science fiction elements and its religious pluralism (Jesus appears on a list of great heroes in the fight against evil, alongside Buddha, Gandhi, and Einstein).

Conversely, secular audiences don’t seem to know what to do with the novel’s explicitly Christian elements. I was horribly disappointed by Disney’s toothless, CGI-filled 2018 adaptation, which trades the novel’s specificity and philosophical depth for meaningless action sequences and a generic “believe in yourself” message.

Nowhere is the novel’s Christianity more blatant, or more moving, than in its final chapter, “The Foolish and the Weak” [spoilers ahead]. Meg’s beloved little brother Charles Wallace is being held in the thrall of the monstrous IT, an evil entity far more powerful than her or any of her friends. As she prepares to face down IT, Meg’s friend Mrs Who - who speaks almost entirely in literary quotations - gives her this “gift”:

“...what I have to give you this time you must try to understand not word by word, but in a flash, as you understand the tesseract. Listen, Meg. Listen well. The foolishness of God is wiser than men; and the weakness of God is stronger than men. For ye see your calling, brethren, that not many wise men after the flesh, not many mighty, not many noble, are called, but God hath chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise; and God hath chosen the weak things of the world to confound the things which are mighty. And base things of the world, and things which are despised, hath God chosen, yea, and things which are not, to bring to nought things that are.” (182)

It’s a bold choice, for a character to quote directly from the Bible at length - specifically, 1 Corinthians 1:27 - in the last chapter of a science fiction novel for children. And yet, this seeming contradiction resonates with the other seeming contradictions that L’Engle found in her own faith. For L’Engle, this idea - that God sides with the discarded and the overlooked, with the foolish and the weak - is at the very heart of the gospel. It is the paradox central to life.

Everyday Deeds of Ordinary Folk

And now I turn, as always, to Tolkien.1

As I mentioned a few weeks ago, I am not overly fond of the Hobbit trilogy, which frequently trades heart and depth for silliness and spectacle. That being said - even as I dislike most of the scenes and characters created whole-cloth for the films - there is one scene from the first film, An Unexpected Journey, that I think fully captures the spirit of the book and the original Lord of the Rings film trilogy.

Why, Galadriel asks Gandalf, has he chosen the fussy and inexperienced hobbit Bilbo Baggins for a dangerous and important quest.

“I don’t know,” Gandalf replies. “Saruman believes that it is only great power that can hold evil in check. But that is not what I have found. I found it is the small things, everyday deeds of ordinary folk, that keeps the darkness at bay. Simple acts of kindness and love. Why Bilbo Baggins? Perhaps it is because I am afraid, and he gives me courage.”

So often, we locate heroism in dramatic - even violent - action. It can be tempting to believe that one must first gain power, then act; or even to believe that the responsibility to act rests only on the shoulders of those individuals who already possess money, power, or a platform. This is the narrative of the heroic individual that underlies so much of American myth-making.

American history, however, is filled with examples of the everyday deeds of ordinary folks, names forgotten or lost, who together made dramatic change. From the suffragettes to Stonewall, we have a tendency to mythologize a few and forget about everyone else whose simple, enduring work propelled them to victory.

I anticipate I will spend more time on the Civil Rights movement and the modes of nonviolent resistance in future issues, but for now I just want to talk about one moment in the vast collective struggle for racial justice: the lunch counter sit-ins.

Though some of us may remember that “The Greensboro Four” ushered in the fight to integrate restaurants and businesses across the segregated American South when they took seats at a “White’s Only” lunch counter at a Woolworth’s, few of us remember their names. Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, David Richmond and Jibreel Khazan are not usually named alongside Martin Luther King Jr. or even Rosa Parks, and yet their act of simple courage - taking seats at a lunch counter and refusing to leave - was transformative.

“Almost instantaneously, after sitting down on a simple, dumb stool, I felt so relieved,” McCain recalled years later. “I felt so clean, and I felt as though I had gained a little bit of my manhood by that simple act.”

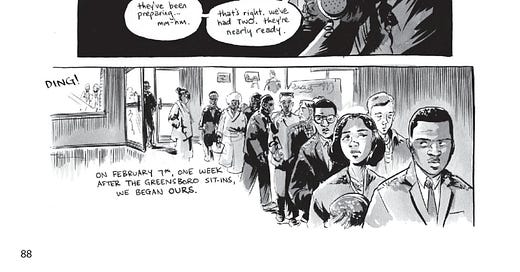

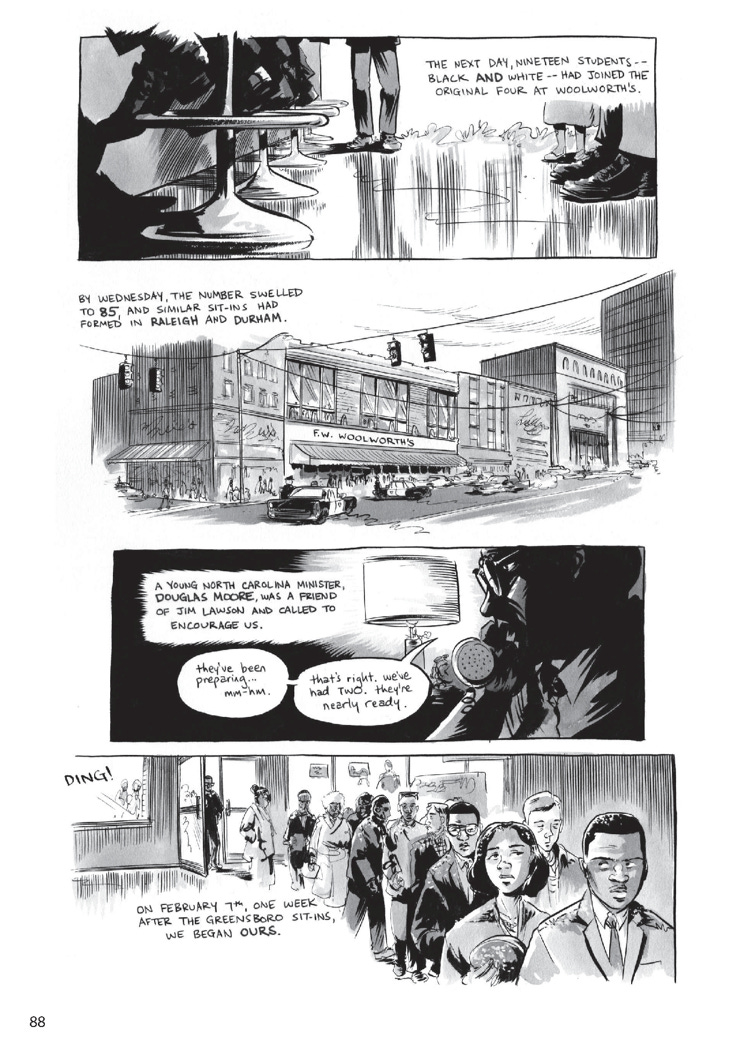

The Greensboro Four’s actions ushered in a powerful chapter of civil disobedience. As Civil Rights activist and congressman John Lewis describes in his graphic memoir March, “The next day, nineteen students - Black and white - had joined the original four at Woolworth’s. By Wednesday, the number swelled to 85, and similar sit-ins had formed in Raleigh and Durham” (88).

As Lewis tells it, the following week, he took part in a similar sit-in, beginning a commitment to civil disobedience that would lead him to jail, across a bridge in the march from Selma to Montgomery, and eventually to Washington D.C.. Lewis went on to become one of the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement - but he began as just another college student willing to participate in an ordinary act of courage.

Famous

It is easy, when telling the story of history, to work backwards: to begin with the people who are renowned now for their courage and point to all their choices and successes as inevitabilities. To do so, however, is to assume certainty where they often experienced doubt; it is to cast a retroactive spotlight on someone who was often only one voice in a chorus.

Naomi Shihab Nye is a Palestinian-American poet who has published or contributed to over thirty volumes of poetry over the last forty years. A persistent advocate for peace, she has been an award-winning working poet for decades, but has never achieved the household name status of someone like Maya Angelou or Robert Frost.

My favorite poem by her is this one from her 1995 collection Words Under the Words:

"Famous"

The river is famous to the fish.

The loud voice is famous to silence,

which knew it would inherit the earth

before anybody said so.

The cat sleeping on the fence is famous to the birds

watching him from the birdhouse.

The tear is famous, briefly, to the cheek.

The idea you carry close to your bosom

is famous to your bosom.

The boot is famous to the earth,

more famous than the dress shoe,

which is famous only to floors.

The bent photograph is famous to the one who carries it

and not at all famous to the one who is pictured.

I want to be famous to shuffling men

who smile while crossing streets,

sticky children in grocery lines,

famous as the one who smiled back.

I want to be famous in the way a pulley is famous,

or a buttonhole, not because it did anything spectacular,

but because it never forgot what it could do.

Courage

I want to finish today’s letter by telling you about my friend Joey Prestley. Joey is one of the funniest, kindest people I know, and he consistently shows up for what he believes in.

Like so many people, Joey is frustrated by the rising cost of living, by rampant disinformation, and by the frequent dehumanization caused by late capitalism. Unlike me, however, Joey is not just complaining: he is running for City Council in District 6 of Green Bay, Wisconsin. “My pledge,” he explains, “is that I will stand for the people - for the working class, for the underserved, and for my neighbors who pay way too much in rent.”

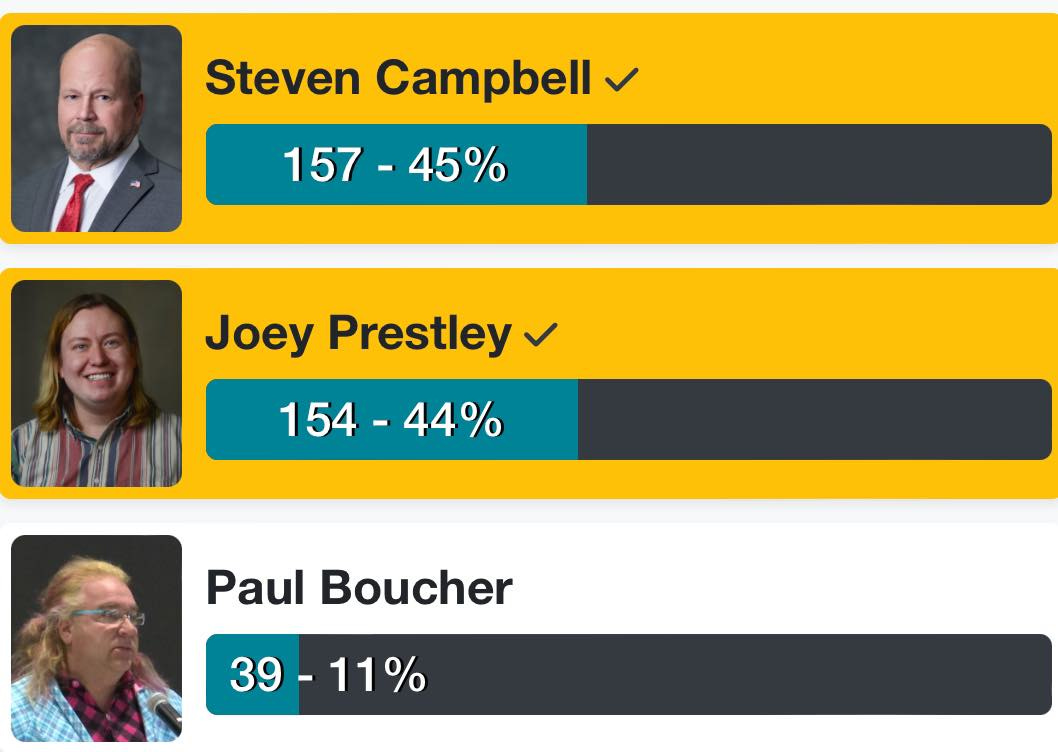

His opponent, incumbent councilor Steven Campbell, is an election denier, a bigot, and a conspiracy theorist. And yet, in the primaries, the two candidates were neck-and-neck. In a district of more than 8,900 people, only 350 voted: 154 for Joey, 157 for Campbell, and 39 for fringe candidate Paul Boucher, a convicted sex offender.

Local politics is not glamorous. It is often kooky, and frustrating, and mundane. Win or lose, news of this race will likely not make it further than the Green Bay Press Gazette. And yet, on April 2, my friend might have the chance to make a real difference for new immigrants, and queer kids, and families being priced out of their neighborhoods. An opportunity for “valor without renown.”

This is the first, and likely the last, time that I will end a newsletter by asking you to donate to a cause. But, if you are a U.S. citizen, consider donating a few dollars to Joey’s campaign. This is a situation where every dollar - and every vote - has the potential to make a tangible difference.

The world is filled with inescapable evil, and staggering displays of power, and seemingly insurmountable odds, and it is so easy to be paralyzed by fear. But Joey - and the millions of people like him who show up and keep working every day to make the world better, whether they are recognized or not? They give me courage.

When it comes to the foolish and the weak, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

This newsletter could very well be called “52 ways of looking at Tolkien,” based on how frequently I anticipate his work will continue to come up. At the beginning of this year, I considered following in the example of the podcast Harry Potter and the Sacred Text and keeping a journal where I read The Lord of the Rings a chapter at a time and reflected on it. I suspect that some of that impulse is being redirected here.

Great. Especially the poem you shared.