Song of the Week: “A Case of You,” by Joni Mitchell - “I could drink a case of you”

Ever since Taylor and I decided to stay in Canada long term, I have half-jokingly begun a program of “educating” him about Canadian culture.

We’ve planned an upcoming weekend trip to Ottawa to visit museums and admire the tulips. He’s become a connoisseur of ketchup chips. And, at the beginning of the month, we attended the Elmira Maple Syrup Festival.

Like many Canadians, I have dim memories of visiting a maple syrup farm - the “sugar bush” - as a child. We tramped through bare and muddy woods, tasting the clear and nearly-flavorless sap that trickled through metal spiles and accumulated in buckets. We gathered around wood fires in smoky sugar shacks, watching bearded men in flannel shirts slowly stir enormous cast iron kettles to painstakingly reduce the sap into syrup. And then, most thrillingly, we feasted on fluffy pancakes, drenched in maple syrup still warm from the cauldron.

I was hoping to gift Taylor a fraction of the magic of this memory when I googled “sugar bush near me,” and discovered that most local farms charged upward of $25 each for a similar experience. And then I discovered that the neighboring small town of Elmira - where we attend a one day Renaissance Faire in a local park each summer - had a maple syrup festival coming up. Admission to the festival was free, pancakes could be purchased for a small fee, and there were bus rides to a sugar bush.

We made plans to go with Jillian and Andy, and did absolutely no more research until midnight the night before. Taylor was exhausted from driving, I had stayed up late finishing a Syllabus about screentime, and we were totally drained. That’s when I discovered that the one-day Elmira Maple Syrup Festival saw 80,000 visitors last year. It is, as signs proudly proclaim, the world’s largest one-day maple syrup festival.1

For reference, the population of Elmira sits around 11,000 people.

“I call it ‘Avoid Elmira Day,’” one resident commented on a Reddit thread. “Traffic is hellish,” another wrote. “Get there at 5:45 am if you want to find parking.”

At this point, we began to laugh a little manically. What were we getting ourselves into? We were burned out. We were stressed. The forecast called for ice cold rain all day.

And yet, for better or worse, to the Elmira Maple Syrup Festival we would go.

Sugar Moon

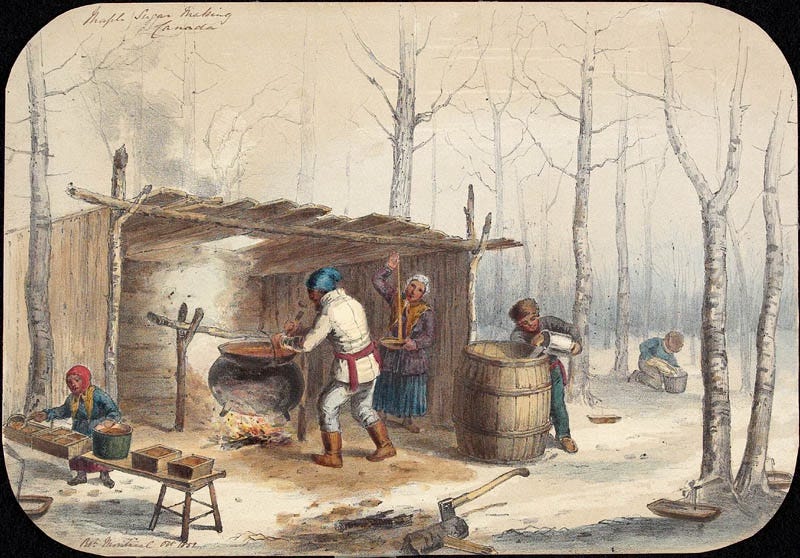

Long before the first European colonizers arrived on the shores of North America, the Indigenous people of Turtle Island knew that maple trees ran sweet. In March, the Anishinaabe celebrated the Zissbaakdoke Giizas, or Sugar Moon, with a dance that welcomed the return of spring. They tapped maple trees and reduced the sap into syrup using clay pots.

Louise Erdrich’s The Birchbark House describes a year in the life of a little Ojibwe girl named Omakayas, who lives with her family on the shores of Lake Superior in 1847.

In the chapter “Maple Sugar Time,” Omakayas and her family experience mixed emotions as they collect sap, boil it down for syrup, and celebrate the return of spring. An unusually harsh winter has left them all frail and sickly, and a smallpox epidemic took the life of her baby brother Neewo.

As Omakayas helps with maple sugaring, she grieves the loss of her brother, and feels guilty that she is enjoying the ritual without him.

“Minopogwud [it tastes good],” said Omakayas, licking up a dollop of thick syrup.

The first taste usually made her smile. Not this time. Sadness overwhelmed her when she tasted the sweetness. She instantly recalled the special day she spent with Neewo on the shore of the lake. On that day, long ago last summer, she had freed him from the tight bonds of his tikinagun, let him tumble and play. When it came time for her to put him back, she’d sweetened his confinement by placing her last bit of sugar on his tongue. (199)

Ultimately, Omakayas’s grandmother helps her understand that she can grieve her brother while also celebrating the sweetness that spring brings. Much like her grandmother before her, she can become a healer.

In Braiding Sweetgrass, Potawatomi botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer writes about her experience turning sap into syrup at home with her daughters. She shares a story from the oral tradition of a time when pure maple syrup flowed directly from trees, and people grew lazy as a result. To prevent them from taking the Creator’s gifts for granted, Nanabozho (The Anishinaabe Original Man) diluted the syrup with water to create sap, ensuring that people would have to work to appreciate its sweetness.

Nanabozho made certain that the work would never be too easy. His teachings remind us that one half of the truth is that the earth endows us with great gifts, the other half is that the gift is not enough. The responsibility does not lie with the maples alone. The other half belongs to us; we participate in its transformation. It is our work, and our gratitude, that distills the sweetness. (69)

When European settlers came to Turtle Island, Indigenous people taught them how to make syrup, and syrup production soon became an important part of colonial life in New France and British North America.

If you read the Little House books like I did, you may remember the moment in Little House in the Big Woods (1932) when Laura Ingalls and her family celebrate maple syrup time.2

After the men have hauled in the buckets of sap and reduced it down to syrup, the family gathers at Laura’s grandparents’ cabin for a dance. The women all get dressed up in their best clothes, and everyone dances together while the room fills with the smells of woodsmoke, baked goods, and syrup simmering down for taffy.

Grandma stood by the brass kettle and with the big wooden spoon she poured hot syrup on each plate of snow. It cooled into soft candy, and as fast as it cooled they ate it…There was plenty of syrup in the kettle, and plenty of snow outdoors. As soon as they ate one plateful, they filled their plates with snow again and Grandma poured more syrup on it. (151)

After making candy, they eat bread and cold pork, pickles and fresh pies. They reduce the syrup further and make cakes of crumbly maple sugar. The next morning, sleepy after the festivities, the whole family eats pancakes drenched in more maple syrup.

“They could eat all they wanted,” the narrator tells us, “for maple sugar never hurt anybody.”

The World’s Largest Sap Bucket

On Saturday morning, we woke early, made coffee, and dressed carefully: old boots we could get muddy, rain jackets, knit hats that we would normally call beanies, but felt like toques today. As we drove through the rain shortly before 9 am, we were relieved to see that the nasty weather had kept away some of the crowds.

Soon, we were enjoying all the delights the festival had to offer: we bought enormous pancakes cooked on outdoor griddles by an army of volunteers, then ate them inside the Lion’s Club hall at long tables, shoulder to shoulder with damp and cheerful strangers. One table over, we saw a young man who looked exactly like Justin Trudeau save for his mustache and mullet, and speculated that he was enjoying some time under cover after finishing his term as prime minister. On our way out of the hall, we saw a volunteer refilling a jug of maple syrup from a full keg of the stuff, and Jillian spotted Amber, the festival’s syrup bottle-shaped mascot.

There was outdoor curling on an inflatable plastic rink. There was maple taffy made with syrup thickened over an open fire and then chilled on snow saved for the occasion.3 There was a pancake flipping contest featuring local political candidates, which we tragically missed.

We also saw the world’s largest sap bucket! Honestly, it was smaller than I expected.

But, best of all, we took that trip to the sugar bush that I was so nostalgic for. We climbed on a school bus that looked like it hadn’t been updated since I was a kid, and rode it ten minutes to a Mennonite-owned patch of maple woods. The path through the trees was thick with mud, and we occasionally squelched off to peek inside the plastic buckets attached to slender maples and see the precious clear sap inside.

Most of the trees, however, were connected by thin blue plastic tubes that led to a shed in a clearing. The man standing next to the door explained that a vacuum machine pulled the sap through the woods to a reservoir, where it traveled through a reverse osmosis machine and collected in a tank.

Next, in the sugar shack proper we saw, instead of the large kettle I remembered from childhood, a large wood-fired evaporator table that quickly concentrated the sap into syrup. “In half an hour, it goes from being 4% sugar to at least 66%,” explained the shy young man who was keeping an eye on the process.

Back outside, we finally tried the family’s fresh syrup, which tasted like butterscotch and botanicals and sunshine. We also ate the best maple cream donut I have ever had, and popcorn made by a little boy using an enormous cast iron kettle suspended over a fire in the yard.

And then, after a bus ride back and a brief browse through the vendors as the rain grew heavier and soaked us to the skin, we went home. We didn’t even buy any syrup; I already have a full liter in my fridge.

What did stay with me was the memory of all the kids I saw that morning: kids carried on shoulders and pushed in strollers and jumping in puddles, speaking languages from around the world, united by the pure euphoria of an event dedicated to eating as much sugar as their hearts desired.

Sticky Business

I first heard about 2012’s Great Maple Syrup Heist from my friend Mercedes back in university. “Did you hear there was a maple syrup heist?” she cackled. “That’s the most Canadian thing I’ve ever heard of!”

In Canada today, maple syrup is serious business. Since 1967, our flag has featured an iconic red maple leaf, and Toronto’s NHL team is the Toronto Maple Leafs. Until we abolished pennies in 2012, they bore an imprint of two maple leaves.

Nowhere is syrup more serious, however, than in Quebec: Quebec produces 91% of all maple syrup in Canada, and 71% of the world’s maple syrup. Last year, Quebec farmers produced 239 million pounds of maple syrup. Altogether, the Quebec maple syrup industry contributes more than $1 billion to Canada’s GDP every year.

Life for maple syrup producers in Quebec, however, is far more regulated than it is for the Mennonite farmers whose sugar bush we visited at the festival in Ontario. Since 1989, all large scale maple syrup production in Quebec must take place through Quebec Maple Syrup Producers (known until 2018 as the Federation of Quebec Maple Syrup Producers). The Federation determines how much syrup farmers may sell each year, and forces them to contribute the rest of their syrup to the Global Strategic Maple Syrup Reserve. Producers only get paid for their reserved syrup when it sells - and the Federation only sells syrup when production that year is low, allowing them to keep maple syrup’s export price stable from year to year.

As you can imagine, not all maple syrup producers are happy with this arrangement. In defiance of the Federation, a thriving black market transports syrup to the neighboring province of New Brunswick, which has much laxer rules around production and export. There, producers can sell their syrup for $1,200 a barrel - almost twenty times the price of oil.

One of the Federation’s most prominent critics is Angèle Grenier, who has been battling the Federation since 2002 for the right to sell her syrup independently. Grenier has paid over $150,000 in legal fees over the last two decades, and finally settled in 2018, agreeing to pay the Federation over $300,000 in fines as punishment for selling her syrup independently. Grenier maintains that, despite the fact she pays taxes on her syrup, she has been treated like a criminal and has lost her freedom. “We don’t own our syrup anymore,” she complained in 2015, referring to the Federation as the maple syrup “mafia.”

With prices high and the Federation making so many enemies, the scene was set for the great Maple Syrup Heist: a crime so absurd and sensational that it inspired not only the highly fictionalized comedy miniseries The Sticky (starring Margo Martindale), but also an episode of the Netflix true crime documentary series Dirty Money.

That Dirty Money episode explains how, in 2012, Federation officials discovered that thieves had stolen almost 3,000 tons of maple syrup, valued at $18.7 million, over the last several months. This was perhaps easier than it should have been: despite the Strategic Reserve being worth hundreds of millions of dollars, at the time it had only one security guard, no cameras, and was inspected only once a year.

Over several months, a trio of thieves stole barrels a few at a time, siphoned off the syrup, and then refilled them with water before returning them to the warehouses undetected. As the operation got greedier, they stopped bothering with this step, simply replacing the barrels empty.

Their crime was revealed when an unsuspecting inspector almost fell while climbing one stack of barrels in the warehouse: he was expecting to be able to support his climb on the 600-pound full barrels, and instead they tumbled out of his way!

The ensuing investigation faced a series of dead ends: maple syrup carries no serial number or tracking information, and stolen syrup tastes just as sweet. The key to the case ended up being marks left on the barrels by a unique kind of forklift the thieves had rented: the police found the rental records, recovered much of the stolen syrup from an exporter in New Brunswick, and arrested five co-conspirators, who paid hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines and served months or years of prison time.

As it turned out, it was partially an inside job: co-conspirator Avik Caron was married to the woman who owned one of the Strategic Reserve’s warehouses!

Despite the heist, the Quebec Maple Syrup Producers are stronger and more powerful than ever, and popular sentiment is still divided between them and the sweet-toothed thieves.

As Grenier concludes bitterly in Dirty Money, “Here in Quebec drugs are decriminalized, but they have criminalized maple syrup.”

The Maple Leaf Forever

The other day in our apartment elevator, a man asked if we had been watching the Toronto Maple Leafs vs. Ottawa Senators game. We hadn’t.

After the man exited the elevator, Taylor turned to me. “I have to pick a hockey team,” he said. “How else will I connect with Canadians?”

I was dubious. “If you start caring about hockey, then I’ll have to care too,” I complained.

Before this year, I’ve always been something of an ambivalent Canadian. I never cared for hockey, or Tim Hortons, or Shania Twain. Honestly, despite all this research and fuss, I don’t even eat that much maple syrup. Outside of the Olympics, where my patriotism knows no bounds, I am far more likely to criticize my country for its violent settler colonial history than I am to express any unconditional love.

I have spent two-thirds of my adult life in the United States, where I was much more comfortable being loudly Canadian. It’s more fun to be a smug international student criticizing gun violence and for-profit health care (while also shopping at Trader Joe’s) than it is to be just another left-leaning citizen.

Then Donald Trump declared an unprovoked trade war on Canada and started threatening our national sovereignty. As he repeatedly referred to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau as “governor” and called Canada the “51st state,” ambivalent Canadians like myself suddenly realized that we could lose a home that we have taken for granted for so long.

As Alberta writer Sarah Bessey reflects in a recent blog post, Trump’s attacks on Canada have reminded her of all the things she loves about this flawed, beautiful, half-frozen place where we live.

Her litany includes silly and inconsequential things, like House Hippos and Mr. Dressup, as well as more serious ones: the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, “Minister and politicians Tommy Douglas bringing universal healthcare to us in the 1960s precisely because of his faith convictions,” and the fact that she is not afraid her children will get shot at school. When she witnesses “bright yellow fields of canola under blue skies in Saskatchewan,” or hears “the call of a loon on a lake” she is reminded that “it isn't perfect and most of us are trying to be honest about that / Canadian culture is as diverse as we are, always evolving / it's ours, ours, ours.”

In the last three months, I have seen more patriotism and national unity among Canadians than I have since Sidney Crosby scored the gold medal-winning goal in overtime during the 2010 Vancouver Olympics. People are planning vacations to Vancouver Island or Newfoundland instead of the United States, cancelling their Amazon Prime subscriptions, and boycotting American brands and groceries. Liquor stores have stopped selling American beer, wine, and liquor altogether. Everywhere you look, store shelves are labeled with little maple leaf stickers proclaiming that potato chips, cheese, apples, and - of course - maple syrup were made by our fellow Canadians.

“Elbows up!” we remind each other, borrowing a term for self-defense during hockey games. As we face economic struggles and global uncertainty, we’re on this team together. Elbows up.

When it comes to the Elmira Maple Syrup Festival, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

As with many such superlatives, the specificity of the title somewhat undermines the impact of the claim.

In more recent years, readers and educators have reckoned with the complicated legacy of the Little House books, which romanticize pioneer life and perpetuate damaging racist stereotypes about Indigenous People. As Sharon Smulders writes in “‘The Only Good Indian’: History, Race, and Representation in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie,” “Insofar as this [mythologization] supports the treatment of frontier culture as the quintessential expression of American values in the Little House books, Wilder simplifies the process of settlement and denies the realities of native experience” (192). Louise Erdrich’s Birchbark House books, which I reference above, were written as a direct response to the Little House books.

Back in February when we went up to the cabin we made maple candy, which French Canadians call la tire. I ate so much of it that I essentially lost my appetite for candy for the remainder of the winter.

What a hardy bunch! I still consider myself a proud Canadian and support my beautiful homeland. Maple syrup and all.