Song of the Week: “I’ll Make a Man Out of You,” from Mulan - “Be a man.”

One of the great delights of this week has been falling in love with Tim Walz, the governor of Minnesota and Kamala Harris’s pick for vice president. Walz rose to prominence in the last few weeks for his clear, no-nonsense style of communication, particularly in his identification of Donald Trump and J.D. Vance as “weird.”

Walz, who grew up in a small town in Nebraska, served in the U.S. Army reserves for more than twenty years, and coached high school football, feels like a prototype of the average American dad - a fact that has led to a lot of memes this week.

“I just know Tim Walz could teach me how to drive stick shift without making me cry once,” Carrie Courogen tweeted.

“Tim Walz pays the bill at Denny’s and then says ‘Let’s rock n roll’ to his family” wrote one fan.

“Tim Walz started putting together his front yard world famous Christmas display in May #BigDadEnergy” quipped another.

Walz is such a delightful figure, I think, because he combines Midwestern sincerity, warmth, and practicality with progressive politics that appeal to common sense.

In the late 1990s, he was the sponsor of his high school’s gay-straight alliance because he believed that a straight football coach was the kind of ally LGBTQ+ kids needed.

He has pushed for affordable day care and paid family leave because he wants to make Minnesota “the best state to raise a family.” Walz is an advocate for reproductive freedom, in no small part because his own daughter, Hope, was born after a long and painful journey with IVF.

His administration passed universal free breakfast and lunch for Minnesota schoolchildren, so that hungry kids could have the nutrition they needed to learn without being singled out or embarrassed.

Walz would be a compelling figure to me in any election, but he feels particularly important in an election where - among other things - masculinity itself feels like it’s on the ballot.

Critics - myself included - have written extensively about the racist, misogynistic, toxic masculinity of Donald Trump and his political hangers-on. Walz himself recently quipped that it seemed like Trump and his running mate, J. D. Vance, were running not to govern America but to be the leaders of the “he-man women-haters club.”

As Amanda Becker wrote in 2021, Trump’s presidency was “marked by his adherence to an amped-up version of hegemonic masculinity, which researchers define as a cultural ideal that prioritizes the dominance of White, cisgender, heterosexual men and traits such as strength and power, over women, LGBTQ+ people, those with disabilities, racial minorities and traits such as cooperativeness and kindness.”

White men as a demographic support Trump more than any other group, and that support holds true even among young people; in fact, as demographic researcher Melissa Deckman writes, young white men “look very conservative compared to even older white men.”

In her book Jesus and John Wayne, Kristin Kobes Du Mez argues that Trump is so popular because he embodies an American heritage of “militant masculinity, an ideology that enshrined patriarchal authority and condones the callous display of power, at home and abroad” (3).

Many of Trump’s supporters, however - especially young white men - see things differently. They feel unwanted, unloved, forgotten, as if there isn’t a place for them in modern society.

As journalist Ezra Klein explained in a recent interview with Gov. Walz:

“There’s also this kind of anger that you see more represented by the Vance side among young republicans. This feeling of families breaking down, that there’s no role for men anymore, that you can’t say anything…“Democrats talk so much about toxic masculinity…They talk about femininity - that the future is female - and that’s good. But one thing I hear when I watch what these young men are watching, when I watch these podcasts or whatever, is this sense from a lot of young men that they’re not wanted in this moment in politics. And Trump wants them and likes them.”

This is a theme, actually, that I’ve been seeing again and again in the last few years: we’re having lots of conversations about toxic masculinity, and what men do wrong, but we are worse at saying what they do right.

What alternatives do we offer for straight white men to the cruelty and dominance of Trump? What role models do we offer our sons? With that question in mind, I wanted to spend the rest of today’s newsletter talking about four more men who - much like Tim Walz - exemplify the best that straight white men can be.

Good Neighbors

There are few cultural figures as universally beloved as Fred Rogers, the Methodist minister and long-time host of the PBS children’s show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. With his cardigans, quiet voice, and frequent songs, Rogers is remembered as a gentle, nurturing presence in millions of children’s lives.

He is less frequently remembered, however, for his courage.

As the excellent documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor? explains, Fred Rogers was a fierce advocate for equality, justice, and accessibility. In 1969, he testified before Congress against proposed cuts to PBS funding, ultimately helping to secure funding for years afterwards.

Going against common wisdom of the time, Mr. Rogers insisted that children deserved to learn hard truths about the world around them in age-appropriate ways: over the years he explained the Vietnam War, the assassination of Robert Kennedy, and 9/11 to his young audience.

Mr. Rogers also used his show to make political statements, so quietly and graciously that it’s easy for modern audiences to miss them entirely. My favorite example is this scene from a 1969 episode of the show in which Mr. Rogers invites Black police officer and frequent character Officer Clemons to share a wading pool with him on a hot day.

At the time, Civil Rights activists were fighting against segregation in public pools across the United States. In his quiet, unassuming way, Mr. Rogers pushed back against structural discrimination, insisting that diversity and inclusion are a vital part of being a good Christian and a good neighbor.

Responsibility

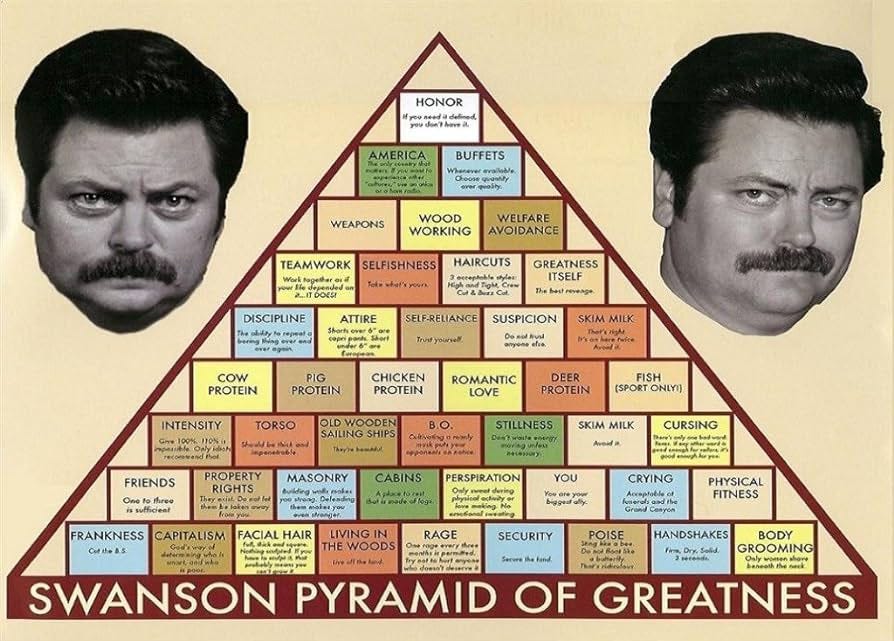

There are few manlier figures in pop culture than Ron Swanson, the libertarian outdoorsmen from Parks and Recreation played by Nick Offerman. Ron hunts, fishes, effortlessly carves wood into furniture and canoes, and prides himself on his business sense and self-sufficiency.

Ron has become a hero for many, in spite of (perhaps because of) his disdain for government services, vegetarians, child labor laws, bicycles, and other things he perceives as weak or dependent.

Ron Swanson comes by a lot of his most impressive traits honestly: his creator, Nick Offerman, shares Ron’s gravelly voice, woodworking prowess, and work ethic. As he explains in this Hot Ones interview while eating spicy wings, Ron’s advice to “never half-ass two things; whole-ass one thing” comes directly from his father.

Self-sufficiency and craftsmanship, Offerman argues, are values everyone should prioritize, regardless of gender.

Sean Evans: You’ve been upheld as a paragon of manhood in this day and age where the very tenets of masculinity are probably more hotly debated than ever. When people can survive perfectly well without knowing how to build a fire or fix a leaky faucet, what do you think is lost when people stop being handy?

Offerman: First thing - I get accused a lot of being manly or masculine, and I suppose some of that must be true, but I come by it honest. It’s what I was born with. I look and sound like this. But I’m actually a very talented ballet dancer, you’d be surprised to learn. I feel like everybody across the spectrum of sexuality should know how to use a screwdriver or change a tire…you know, things break, and those of us who know how to fix things when they break end up being better responsible members of our community.

Crucial to Offerman’s ethos - and missing from Ron Swanson’s libertarian mindset - is the role that individuals should play in supporting each other. When we work hard and build skills, he argues, we can use those skills to show up for each other and take care of each other.

Brother, Captain, King

The Lord of the Rings is, in many ways, a text about masculinity. As I have discussed before, there are very few female characters in the book, and even less in the films.1

That is, in large part, because the books can be read as Tolkien’s response to his experience as a soldier in World War I. The relationship between the nine members of the Fellowship - particularly the relationship between the four hobbits - exemplifies the courage, loyalty, and self-sacrifice that Tolkien saw demonstrated by his fellow soldiers in the face of violence and horror.

Though Lord of the Rings serves as the blueprint for much of modern fantasy, however, it does not share the glamorization of violence, sexual exploitation, and individual glory that shows up in so many modern fantasy works. Though the books feature their share of great warriors, such as Boromir and Eomer, its protagonists are those who heal both creatures and creation. As Lore Arnold writes, “The goal of the heroic men of The Lord of the Rings is to build a world in which they can stop fighting - and that goal is achieved.”

Though the cast is largely made up of men, it is Aragorn, the heir to the throne of Gondor, who has stood out to me since I was a kid as the ideal of masculinity.2

As therapist Jonathan Decker and filmmaker Alan Seawright describe in their analysis of Aragorn, Aragorn is a rich, complex character who demonstrates the weakness and insecurity of toxic masculinity through his own confidence and strength. A better term than “toxic masculinity,” they suggest, might be “limiting masculinity” - in which men are not able to experience a full range of emotions because of their own fear of being perceived feminine, weak, or incompetent.

A skilled outdoorsmen and warrior, Aragorn leads the hobbits through the wilderness, protects them from the Nazgul, leads armies in Rohan and Gondor, and unites the people of Middle Earth in their final stand against Sauron. He also sings and recites poetry, respects and empowers Eowyn, cries and is physically affectionate with other men, and heals people’s wounds. As one prophecy predicts, “The hands of the king are the hands of a healer.”

Curiosity

One of my favorite TV shows of the last decade is about another midwestern football coach: Ted Lasso.

Ted Lasso depicts how a cheerful football coach from Kansas leads a struggling English football (soccer) team, AFC Richmond, to victory. Ted begins the show as a seemingly naive Ned Flanders figure in a sea of cynical, competitive, and cruel Brits, but as the show progresses he transforms the attitudes of the people around him even as he is forced to confront his own buried trauma. Even as Ted encourages his players like Jamie Tartt and Roy Kent to repair their relationships with others and build more secure senses of self-worth, he has to grapple with his own anxiety disorder and fears about how to be a long-distance parent while going through divorce.

By the end of the show, Ted is a better coach and a better father specifically because he is able to confront and accept his own fear, grief, and failure. Paradoxically, that willingness to be vulnerable and accept negative emotions makes his joy, good humor, and curiosity even stronger.

In one of my favorite scenes from the show, Ted plays darts at a local bar against Rupert Mannion, the wealthy, cruel, and womanizing former owner of AFC Richmond. Rupert has been nothing but condescending to Ted since his arrival, assuming that his cheerfulness and folksy wisdom translates to incompetence.

You know, Rupert, guys have underestimated me my entire life. And for years, I never understood why. It used to really bother me. But then one day, I was driving my little boy to school and I saw this quote by Walt Whitman and it was painted on the wall there. It said, ‘Be curious, not judgmental.’3 I like that. So I get back in my car and I’m driving to work and all of a sudden it hits me. All them fellas that used to belittle me, not a single one of them were curious. They thought they had everything all figured out. So they judged everything, and they judged everyone. And I realized that their underestimating of me - who I was had nothing to do with it. Cause if they were curious, they would have asked questions.

Ted Lasso teaches us that the kind of masculinity exemplified by Donald Trump and his followers is a masculinity based on insecurity and fear.

True masculinity lies in having the confidence to know that other people’s success does not threaten your own. It means being curious about the perspectives and stories of others, using your strength to protect others who can’t protect themselves, and lending your voice to advocate for the voiceless.

It means knowing how to build a table - and then ensuring that everyone has a place at it.

When it comes to straight white men, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

There are actually less named women than horses in LOTR!

Indeed, Aragorn is such an ideal man that real-life men struggle to measure up, as cheekily noted by this Reductress article, “Why I’m Settling for a Man Who’s Not My High School Poster of Aragorn.”

As far as I can tell, Walt Whitman never said this, so we’ll attribute this wisdom entirely to the creators of Ted Lasso.

Great piece! When it comes to real men in the public eye, I feel like the Green brothers have to make the list of good masculine role models, too.