Song of the Week: “Tiny Glowing Screens Pt. 1,” by Watsky - “When the sun burns out / We'll light the world with tiny glowing screens”

I almost didn’t write a Syllabus today.

Between an unusually busy week at work, plans that took me out of the house until late the last three nights, and a chosen topic that ended up requiring more research than I could do right now, I thought I would have to send you an apologetic “wait till next time” note. I just didn’t have the time.

What I did have time for, however, was spending twenty-eight hours on my phone.

Ever since iPhone introduced the Screen Time feature, I have been haunted by detailed data about how much time I spent actively using my phone: an average of five to six hours a day.

At first, I thought that number must be incorporating time I spent navigating with Google Maps, or listening to music or audiobooks while commuting and doing chores, but no! That figure only includes time when my screen is on.

In other words, I am currently spending 25% of my life on my phone.

WHACK-A-MOLE

When I look at a number as stark as this, I want to find excuses or justifications. I use my phone to pay for purchases, figure out my public transit schedule, organize my to-do list, and take photos of funny things I see throughout my day. Most justifiably, I check out a lot of library books using the Libby app, and read them on my phone.

Also, my husband currently lives in Detroit five days out of seven, and I spend a lot of time texting him, sending him memes or photos, and occasionally having hours-long video calls while we putter around our respective apartments. And the data does reflect that. Last Saturday, a day that I spent delivering an academic presentation, reading and knitting at a cafe with friends, and cooking with Taylor, I clocked a measly three hours on my phone.

Like so many other people today, I know my screen time is making me lonelier, more anxious, and more stressed. I’ve tried different tactics to counteract my screen addiction, but often it feels like playing a game of Whack-a-Mole: I eliminate one source of anxiety or distraction, and another takes its place.

In grad school, I was an active user of Twitter: I followed a lot of writers and comedians, and even had a Tweet go viral once and end up in a Buzzfeed roundup.1

I quit, though, during the pandemic, because the hot takes and emotional whiplash were getting under my skin.

Then, from 2020 to 2024, I spent hours a day on TikTok at the whims of the algorithm. I’d watch a montage of vintage fall outfits, a three-minute scientific explainer by Hank Green, and footage of an atrocity happening on the other side of the world in rapid and jarring succession, leaving me emotionally disoriented but no less absorbed.

The day after the election, to protect my already devastated mental and emotional health, I deleted TikTok. I miss it constantly: I miss discovering new music and being part of The Discourse, seeing high-definition footage of concerts and fan edits of my favorite movies. But I don’t miss the way it made me feel tired and neurotic and overwhelmed.

Right after I deleted TikTok, however, a funny thing happened: every time I was waiting in line or sitting on the toilet, I ended up scrolling mindlessly through Instagram. I have used (and loved!) Instagram for more than a decade, but now I wasn’t using it to see my friends’ dogs or share step-by-step photos of my baking experiments. I was just here to scroll: to laugh, and cringe, and rage, and worry, until my poor overstimulated brain couldn’t handle it anymore.

After a day where I spent multiple hours alternating between scrolling Instagram and tearfully panicking about the Trump administration, I knew I was out of control. So for the first time, I’ve used my phone’s app limiting function to shift the way I use my phone. Between 11 pm and 9 am, I am banned from email, Instagram, and even the NYT Crossword. Perhaps most importantly, I am limited to only half an hour of Instagram use a day, so I have to spend it wisely: to actually post pictures and share with people I love.

I realized I was getting freaked out by breaking news while grocery shopping, so I turned off email push notifications. Every time I checked the time I started scrolling, so I bought an analog watch, which worked for two weeks before the winding pin fell out and it stopped. I went to the library in person and got a stack of physical books so I could read without interruptions.

I tried to give up Reddit for Lent (I doomscrolled for four hours this week not counting my laptop). A couple weeks ago, I managed to spend six hours over the course of the week playing a generic version of Queens, a new game introduced by LinkedIn.2

And now, I regret to inform you, I have started mindlessly doomscrolling on Substack.

Whack-a-mole, whack-a-mole, whack-a-mole.

And I’m not alone in any of this. A recent study showed that 38% of American teenagers, and 47% of parents, believe that they are spending too much time on their respective phones. In 2020, the Oxford English Dictionary named “doomscroll” one of its words of the year. In 2024, they added “brain rot.”

On average, we’re all spending less time with our friends, having less sex, and engaging less in hobbies and community groups than people were in previous decades. We are more anxious and overwhelmed and self-conscious and depressed than ever before. As Magdalene J. Taylor writes bluntly in a 2024 essay, “It’s obviously the phones.”

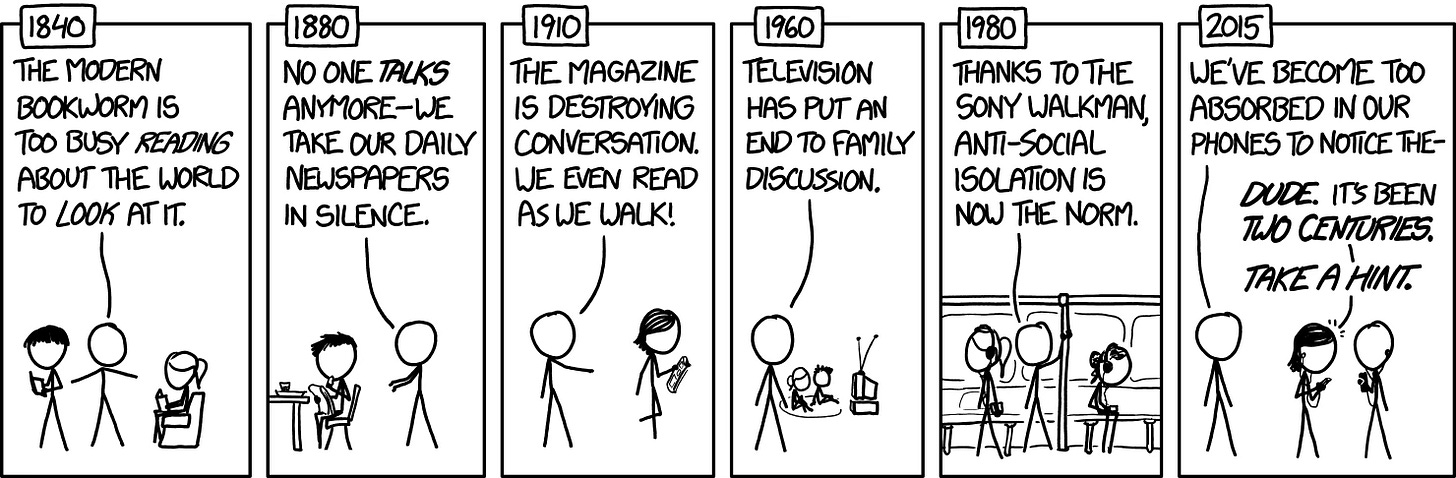

While it’s true that every generation has bemoaned how new technology affects people’s attention spans and interactions, this moment is different. “People have been consuming copious quantities of media for decades now,” Taylor writes, “but it wasn’t until the smart phone, a device we carry with us at nearly every moment, that we began to be so alone. Neither books nor television simulate socialization in the way our phones do.”

Cautionary Tale

This month, my work book club read Ray Bradbury’s dystopian classic Fahrenheit 451. We had chosen it because of our anxieties around book banning and threats to free speech under the Trump administration: the novel is famous for its firefighters who burn books instead of saving homes from fires. I last read the novel in university, and I mostly remembered a scene near the end where the protagonist discovers a group of heroic people who have memorized entire texts, preserving the now-banned books by becoming living books.

What I discovered on the reread, however, was a novel about screentime. Bradbury wrote Fahrenheit 451, which was published in 1951, because of his concerns about the newly-introduced medium of television.

The protagonist, Guy Montag, lives in a world where people spend all of their time outside of work either recklessly seeking adrenaline rushes or watching a never-ending stream of mindless, pointless entertainment. His zombie-like wife Mildred spends her days staring at the three wall-sized screens in their living room where she follows the exploits of characters she refers to as her “family.” Every night, she ignores her husband and listens to music and radio programs through her “Seashells,” her in-ear radios. Sometimes, she pays extra to “participate” in the shows she’s watching, in which the characters occasionally robotically say her name, or pause for her to contribute predetermined lines. Despite this endless entertainment, of course, Mildred is miserable beneath her constant distraction, and the characters’ marriage has withered so entirely that they can no longer remember how they met.

“When we read this in school in the 1980s, it was a cautionary tale,” my coworker Fiona remarked. “Now it feels much more like it’s here.”

But, of course, we’re not quite there yet. In the world of Fahrenheit 451, books have been banned, and possessing them leads to punishment or death. Before such a total book ban could take place, however, society had to stop valuing them. Gradually, Guy’s villainous boss Beatty explains, attention spans shrank, and people grew impatient with the complexity and difficulty of literature and art.

Classics cut to fit fifteen-minute radio shows, then cut again to fill a two-minute book column, winding up at last as a ten- or twelve-line dictionary resume….Politics? One column, two sentences, a headline! Then, in mid-air, all vanishes! Whirl man’s mind around about so fast under the pumping hands of publishers, exploiters, broadcasters that the centrifuge flings off all unnecessary, time-wasting thought! (52).

This lack of individual attention, Beatty explains, leads to general complacency as society changes.

School is shortened, discipline relaxed, philosophies, histories, languages dropped, English and spelling gradually neglected, finally almost completely ignored. Life is immediate, the job counts, pleasure lies all about after work. Why learn anything save pressing buttons, pulling switches, fitting nuts and bolts? (53).

Ultimately, Beatty says, university humanities departments closed in favor of weapons research. People stopped caring about corruption in their government or wars being waged by their country beyond its borders. Instead of seeking to understand the world and the people around them carefully and complexly, they filled their lives with meaningless tasks to do and an endless stream of color and noise.

As a professor in hiding explains to Guy later in the novel, “The public itself stopped reading of its own accord” (83).

More Sense than Reality

When I taught undergrad English, I discovered that my students were often big fans of the 1990s sitcom Friends. This was surprising to me: the show has been criticized in recent years for its lily-white cast, frequent homophobic and transphobic jokes, and other regressive attitudes best left in the 90s.

An article by Melanie McFarland, however, helped shed some insight on Gen Z’s love for Friends. McFarland argues that they see it as a nostalgic period piece about a time when people spent most of their leisure time hanging out together in person and actually interacting. Members of Gen Z, McFarland writes, have grown up in a world where:

…people are more likely to communicate via text than call each other on the phone, more likely to stare into a small screen to consume a show than share the experience with others on a TV, and more likely to search for answers from strangers on the Internet than source knowledge from peers or relatives.

In this world, where people are more likely to seek out romance or make new friendships with the assistance of an online service, Friends makes more sense than reality.

Of course, the friends don’t live an entirely screen-free life: they watch TV (mostly together), and in season 2 (set in 1996), Chandler buys a chunky laptop with a 500 MB hard drive, much to everyone’s bemusement.

For the most part, however, the six friends live a life that seems charmingly analogue, as foreign to contemporary viewers as Marty McFly’s parents’ 1950s world was to him. The friends go on dates with people they meet at bars or waiting for the elevator. They sit around flipping through magazines, and take phone messages down on pads of paper. They talk, about everything and nothing, while drinking lattes at Central Perk.

Of course, there is nothing stopping us today from asking people out at bars, or reading magazines, or talking over lattes. But the absence of phones feels significant: they aren’t there as a seductive alternative.

There’s a 2012 episode of my favorite sitcom, Parks and Rec, where Tom Haverford gets into a car accident because he’s using Twitter while driving, and the judge sentences him to a week without screens as a punishment.

Stripped temporarily of his computer and his cellphone, Tom is unable to navigate to work, and he spends his time pinning pictures to a corkboard (in lieu of Pinterest) and tapping on a cardboard rectangle he’s created to replace his iPhone.

Tom’s screen addiction is played for laughs, of course, as is the absurd amount of different things he’s doing online: every day he visits every major social media site, goes down rabbit holes on Reddit and on Wikipedia, and listens to multiple podcasts. “This is the work of a lunatic,” the grumpy outdoorsman Ron Swanson declares. “You need to detox.”

Thirteen years later, the cardboard iPhone still feels silly. The rest of it? Not so much.

Good Rain and Black Loam

So how do we save ourselves from living in the world of Fahrenheit 451?

The truth is - I don’t know. I don’t think there is a simple solution.

I was at a party where one of the attendees spent a large portion of the evening singing the praises of “dumb phones”: expensive, custom-built devices that only perform a very limited number of functions, such as texting and map navigation. Ironically, that same man spent hours each week moderating a subreddit dedicated to the pleasures of dumbphones.

Dumb phones might work for some people, but I am suspicious of the ways in which our culture sells us a problem, and then sells us a solution to that same problem. Is the cure to our technology addiction really another piece of technology?

Perhaps, for some people, it is.

But the truth is that these devices of ours are immensely useful when we are actively living in the world. We can check decibel levels at concerts, use Google Translate to help a lost tourist, and FaceTime relatives far away.

Teenagers today might romanticize the early 2000s, but I remember how time-consuming it was to load up on everything you would need for the day ahead: a compact to check your makeup, a notebook or day planner, change for payphones, tapes or CDs to listen to in the car, paper maps if you were going somewhere unfamiliar, and on and on. I can rant about screentime as long as I want, but I can’t deny the lightness I feel when I walk out the door in the summer with nothing in my pocket but my phone, my keys, and a pair of earbuds.

The problem, I think, is when our phones stop being tools that empower us as we interact with the world around us, and become the world with which we interact. We buy makeup that promises to give us poreless, TikTok-filter perfect skin. We go to family dinners and then spend our time sitting on our separate devices. We throw parties where we spend more time livestreaming how much fun we’re having for Instagram than we do playing games with our guests. But all is not lost.

Last year, Apple put out an ad for its new iPad Pro that, thankfully, received a swift and immediate backlash.

We see an enormous hydraulic crusher descend from the ceiling destroying all manner of things used for creativity and self-expression: musical instruments, cans of paint, leather-bound notebooks, cameras. As they shatter and explode, the ultra-thin iPad survives: outlasting and replacing them all.

“The destruction of the human experience. Courtesy of Silicon Valley,” actor Hugh Grant wrote (ironically, on Twitter). “Tech and #AI means to destroy the arts and society in general,” said SAG-AFTRA advisor Justine Bateman. But it was filmmaker Reza Sixo Safai’s response that I found the most insightful: she simply reversed the clip.

This time, an iPad is crushed beneath a press, then that overwhelming destruction is pushed back by music, by writing, by art.

As the professor in Fahrenheit 451 notes, the books themselves were not unique: rather, they - along with art, music, film, friendship, and nature - provided complex and truthful looks at human experience. “Now do you see why books are hated and feared?” he asks. “They show the pores in the face of life. The comfortable people want only wax moon faces, poreless, hairless, expressionless. We are living in a time when flowers are trying to live on flowers, instead of growing on good rain and black loam” (79).

I truly believe that it is possible for us to learn to control our phones instead of letting them control us. We can learn to reject the apps and behaviors that destroy us while still using these powerful tools to communicate and navigate the real, messy, complex world. We can replace hours spent on Instagram and Reddit with live music and forest walks and community activism and art projects and epic novels and unpolished, meandering conversations with the people we love.

We have everything we need. We just have to look a little further than the palms of our hands.

When it comes to screentime, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

It was criticizing the Trump administration in their early days, and also got me my very first online death threat!

I hate LinkedIn, but I love a little logic game. Frustrated by the fact that LinkedIn only releases one game of Queens a day and doesn’t have an archive, I sought out a way to waste my week on it