Song of the Week: “Mom,” by Earth, Wind & Fire - “Mom, she gave me pains and joy”

I still remember the first Mother’s Day gift I ever picked out.

My dad took my brother and I to a craft store – I couldn’t have been older than six – and I carefully selected a rubber stamp depicting a mouse eating an enormous strawberry. The woman at the store demonstrated how one could stamp the strawberry in a vivid reddish-pink ink, then use clear glaze and a heat gun to add a glossy plastic shine to the fruit’s surface. My father bought the entire kit on our behalf, and I truly could not imagine a more magnificent and fitting present for my craft-loving mother.

For months afterward, whenever she incorporated that mouse and his strawberry into a card, I looked upon the finished product as proudly as if I had been its sole architect from idea to delivery.

My pride at this first tiny Mother’s Day gift reminds me of one of my favorite poems by the American poet Billy Collins, entitled “The Lanyard.”

The other day I was ricocheting slowly

off the blue walls of this room,

moving as if underwater from typewriter to piano,

from bookshelf to an envelope lying on the floor,

when I found myself in the L section of the dictionary

where my eyes fell upon the word lanyard.

No cookie nibbled by a French novelist

could send one into the past more suddenly—

a past where I sat at a workbench at a camp

by a deep Adirondack lake

learning how to braid long thin plastic strips

into a lanyard, a gift for my mother.

I had never seen anyone use a lanyard

or wear one, if that’s what you did with them,

but that did not keep me from crossing

strand over strand again and again

until I had made a boxy

red and white lanyard for my mother.

She gave me life and milk from her breasts,

and I gave her a lanyard.

She nursed me in many a sick room,

lifted spoons of medicine to my lips,

laid cold face-cloths on my forehead,

and then led me out into the airy light

and taught me to walk and swim,

and I, in turn, presented her with a lanyard.

Here are thousands of meals, she said,

and here is clothing and a good education.

And here is your lanyard, I replied,

which I made with a little help from a counselor.

Here is a breathing body and a beating heart,

strong legs, bones and teeth,

and two clear eyes to read the world, she whispered,

and here, I said, is the lanyard I made at camp.

And here, I wish to say to her now,

is a smaller gift—not the worn truth

that you can never repay your mother,

but the rueful admission that when she took

the two-tone lanyard from my hand,

I was as sure as a boy could be

that this useless, worthless thing I wove

out of boredom would be enough to make us even.

The absurdity of Mother’s Day is also its charm, I suppose. Here is breath and food and love and care, our mothers say, and we reply: here is a lanyard, or a scribbly construction paper card, or a mason jar covered in spray-painted macaroni, or a rubber stamp of a mouse eating strawberries. How could we be clearer in our gratitude?

These gifts, of course, as any mother will tell you, truly are meaningful in their sweetness and sincerity. Less meaningful are the ways that our society has neatly co-opted Mother’s Day - as it co-opts all holidays - as an excuse for buying things. In this segment from Last Week Tonight, comedian John Oliver presents increasingly absurd things advertised for Mother’s Day, from commemorative baseball flower pots to a special at Hooters where moms eat free.

These crass and ridiculous suggestions for Mother’s Day are particularly absurd, he argues, in the United States, which is one of only only a handful of countries in the world that does not guarantee people some kind of paid parental leave.1 Oliver points to the example of Minnesota politicians who made public messages thanking their mothers and wives, but then voted against bills increasing protections for new moms because they claimed it would hurt the economy.

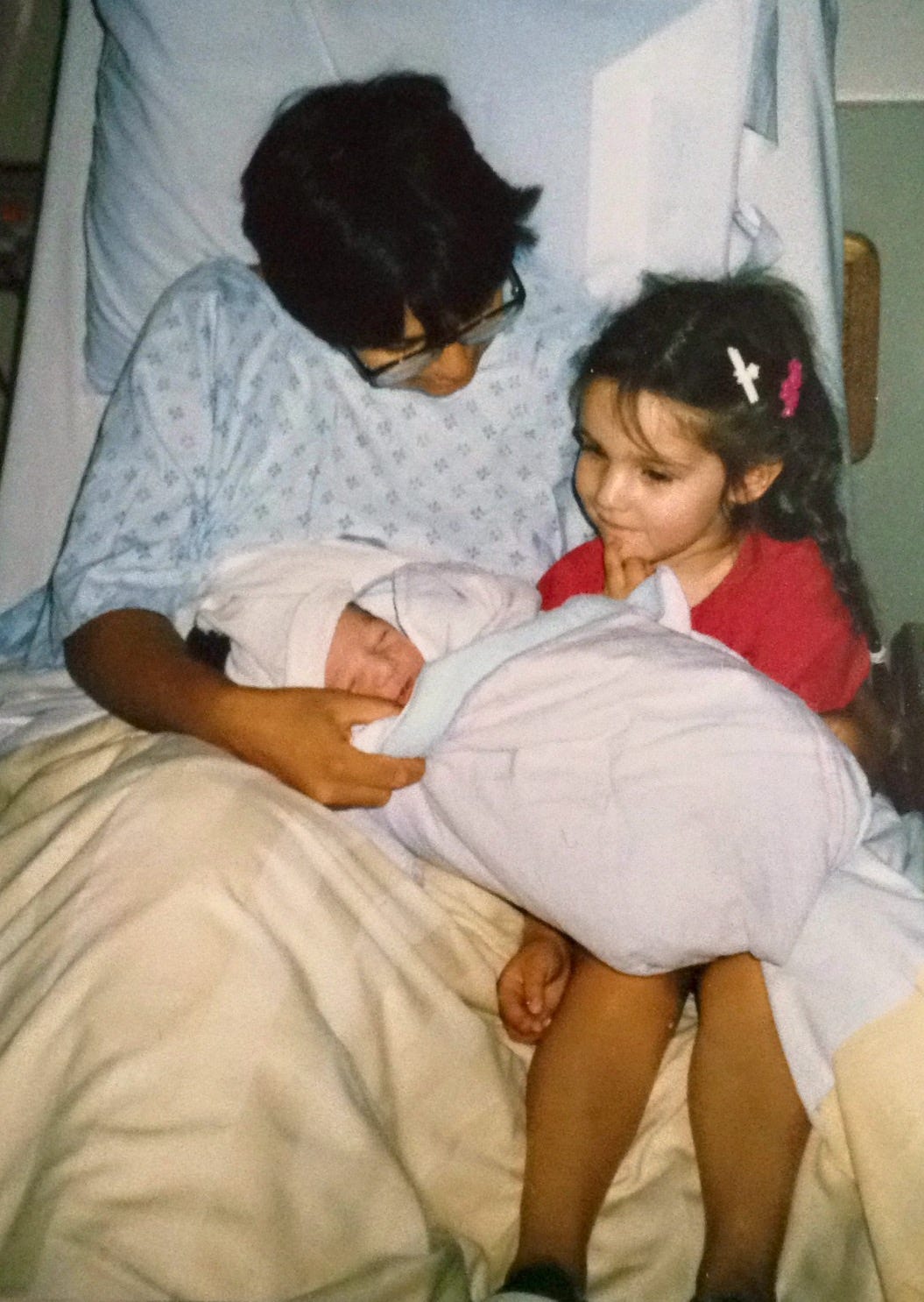

Loudly claiming to love and appreciate mothers, it would seem, is not the same as giving them the gift they desperately want: the gift of time with their babies.2

The Spectrum of Motherhood

As much as Hallmark cards and advertising campaigns might push a homogenous picture of mothers, not all motherhood looks the same. It can be easy to act as if motherhood is always an uncomplicated question of right and wrong, and then to judge everyone who does not conform to your preference: unmedicated vs. medicated birth, breastmilk vs. formula, stay-at-home mom vs. career woman with childcare, free-range parenting vs. regimented schedule of extracurriculars.

In her memoir Yes Please, comedian Amy Poehler describes how motherhood forced her to adopt a mantra that she repeats frequently: “Good for her, not for me.”

Of course, there are some instances where I think there are clear right and wrong choices - for example, vaccinating your children - but for the most part, motherhood is a far richer and more complex tapestry than we often imagine it to be.

I love the spectrum of motherhood highlighted on Cup of Jo, the enormously successful lifestyle blog founded in 2007 by Joanna Goddard. Cup of Jo balances chatty makeup tips and easy dinner recipes with serious conversations about race, sexuality, aging, grief, and relationships, but it is particularly interested in questions surrounding parenting. From 2013 to 2017 Cup of Jo featured a wonderful series about parenthood around the world, from Namibia to Iceland.3 Other coverage has included honest accounts of miscarriage and infertility, questions about transracial adoption, and discussions of the pain and joy of foster parenthood..

One of my all-time favorite posts from Cup of Jo is this 2021 article, “”What Is Disabled Motherhood Like?” The author, Kelly Dawson, talks about growing up with cerebral palsy and not having any cultural images of what motherhood might look like for her. “I don’t have any pop culture references of an effortlessly calm disabled mom telling her child that it’ll all be better in the morning,” she writes, “or even everyday observations of visibly disabled moms running errands while their kids ask for cookies in the background.”

That’s why discovering Rebekah Tausig’s Instagram account was so important for her. Tausig is a disability advocate, and parents her son Otto from a wheelchair. In the article, Dawson interviews Tausig about the challenges and joys of disabled motherhood. Being disabled, Tausig writes, prepared her for motherhood in unexpected ways:

I know with my body, everything can be figured out and nothing stays the same. I will find the resiliency I need until it changes, and the same goes with raising a baby. I think my disability has given me the skill set to know how to work with unpredictability and frustration, and that flexibility and endurance flows over into motherhood as well.

I also think, like motherhood, having a disability is like being in a secret club. You and I have never met in person but we understood each other on a deep and personal level. And that’s true with parenting, too.

Tausig also talks about how strange it was to be described, for the first time in her life, as medically “normal” - pregnancy came with a script that she was able to follow, which she found simultaneously disquieting and freeing.

I encountered a different kind of unrepresented motherhood when I recently picked up Amie Klempnauer Miller’s She Looks Just Like You at the thrift store. The book is the memoir of a lesbian woman whose partner gave birth to their daughter – in other words, she is in the relatively unique position of being a woman who is about to become a mother without adopting or being pregnant herself.

I just started reading the book this week, but I’m immediately struck by how little space our culture makes for situations like the author’s – and how much less space there was when the book was published in 2010. Klempnauer Miller talks about the frustration and disappointment she went through during a year and a half of trying to get pregnant, and the mingled envy and joy she felt when her wife Jane was immediately able to get pregnant on her first try.

She describes the weirdness of shopping for donor sperm, and the women’s shared anxiety that if they asked for sperm from a man they knew then he might ultimately have more of a legal right to their child than one of the child’s mothers. Unable to find much advice for anyone in her situation, Klempnauer Miller buys a book for stay-at-home dads, one of the only resources that both acknowledges she will not be pregnant while also trusting her to be both competent and nurturing. As she and her wife start their family together, she contemplates how simultaneously strange and familiar their experience feels:

We were part of intersecting modern phenomena: medically assisted conception and the so-called gayby boom. But we were also part of a timeless tradition: two people coming together in love, hoping to make a new life. The possibility of becoming pregnant felt like venturing into a rushing stream, not knowing where the current would take us. I closed my eyes and trusted that there were stepping stones under the water, made of history and dreams, and that our feet would find them. (18)

Sins of the Mother

The dark side of our cultural adulation of mothers, of course, is that not all mothers are good mothers.

This week, I read Abby Jimenez’s wonderful romance novel Just For the Summer, which follows two people trying not to fall in love with each other while coping with the ways that their mothers have profoundly failed them.

Justin, a software engineer in his mid-twenties, suddenly has to become the legal guardian of his younger siblings after his mother is sentenced to prison time for embezzling from the non-profit where she works. For Justin, who grew up in a happy and stable household until his father was killed by a drunk driver three years earlier, his mother’s crime is a failure of responsibility and a betrayal of his image of her. Still, by the end of the novel he is able to further understand her grief and remorse for these actions, and reassures her that he is able to care for his siblings because “you showed me how” (193).

Justin’s love interest Emma, on the other hand, has had a far more tumultuous childhood, including periods of abandonment and multiple stints in foster care. Raised by an erratic single mother who constantly uprooted their lives and sometimes left her behind for days or weeks at a time, Emma struggles both with an inability to form deep relationships and with an enduring love for and allegiance to her mother even as an adult. Emma constantly finds herself cleaning up her mother’s messes even as she makes excuses for her behavior, until she is finally able to recognize the ways that her mother neglected and abused her. “My mother’s neglect wasn’t the product of mental illness, or lack of resources, or circumstances beyond her control, the inability to do better,” she realizes. “My life was chosen for me. It was chosen by her” (353).

Even typing those words - acknowledging that mothers can be vindictive, abusive, and cruel - feels taboo. Our culture has plenty of space to talk about the ways that fathers fail us, but we rarely acknowledge how painful holidays like Mother’s Day can be for those whose mothers failed them.

Child actress Jeanette McCurdy’s shockingly-titled memoir I’m Glad My Mom Died details the ways in which an overly involved and narcissistic mother can also leave deep psychological wounds. A shy child in a deeply dysfunctional family, McCurdy was forced to begin acting at a young age by her mother, who had never achieved her own dreams of stardom. McCurdy’s mother intentionally gave her an eating disorder to delay puberty, insisted on bathing her until she was eighteen, and controlled every aspect of her career from what jobs she took to her sleeping arrangements. When her mother died of cancer, McCurdy was devastated. Only after years of therapy was she able to acknowledge and heal from her mother’s abuse - and find meaning and a career outside of the one forced upon her.

At the end of the memoir, standing over the tombstone memorializing her mother as brave, kind, loving, insightful, and on and on and on, she reflects bitterly:

Why do we romanticize the dead? Why can’t we be honest about them? Especially moms. They’re the most romanticized of anyone.

Moms are saints, angels by merely existing. NO ONE could possibly understand what it’s like to be a mom. Men will never understand. Women with no children will never understand. No one but moms know the hardship of motherhood, and we non-moms must heap nothing but praise upon moms because we lowly, pitiful non-moms are mere peasants compared to the goddesses we call mothers. (303)

Fortunately, for most of us, our mothers fall somewhere between pervasive abuse and angelic perfection. It’s easy to forget that our own mothers were also learning how to be mothers for the first time, and doing the best they could. My friend Amy sent me this video the other day, in which the author reflects on how, as she grew up, she was watching her mother grow up too:

Her mother, the video creator realizes, was “just a girl herself who brought a daughter into this world, and when she’s anxious or contemplative or sad wants to talk to no one other than her own mother.”

Under Her Raincoat

While Billy Collins’s “The Lanyard” makes me laugh, my favorite poem about motherhood is Ada Limón’s “The Raincoat,” in no small part because my mom drove me to weekly physiotherapy appointments for much of sixth and seventh grade.

When the doctor suggested surgery and a brace for all my youngest years, my parents scrambled to take me to massage therapy, deep tissue work, osteopathy, and soon my crooked spine unspooled a bit, I could breathe again, and move more in a body unclouded by pain. My mom would tell me to sing songs to her the whole forty-five minute drive to Middle Two Rock Road and forty- five minutes back from physical therapy. She’d say, even my voice sounded unfettered by my spine afterward. So I sang and sang, because I thought she liked it. I never asked her what she gave up to drive me, or how her day was before this chore. Today, at her age, I was driving myself home from yet another spine appointment, singing along to some maudlin but solid song on the radio, and I saw a mom take her raincoat off and give it to her young daughter when a storm took over the afternoon. My god, I thought, my whole life I’ve been under her raincoat thinking it was somehow a marvel that I never got wet.

Thank you, Mommy, for always holding me under your raincoat. Happy Mother’s Day.

When it comes to Mother’s Day, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

In this segment, from 2016, Oliver names the United States and Papua New Guinea. This 2023 New York Times article lists six: the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Nauru, Palau, Papua New Guinea, and the United States.

I won’t spend too much time talking about the pregnancy and childbirth aspects of motherhood in today’s Syllabus, both because they represent only a small (albeit dramatic) part of motherhood, and also because I’m planning to spend an entire future issue on the subject.

Though the series has its limitations - many of the featured subjects are Americans who moved to these countries to work or study and then got married and started families. In recent years, Goddard has made a concerted effort to not only feature American voices.

Well thanks, I'm sobbing