Song of the Week: “Graduation (Friends Forever),” by Vitamin C - ““When we leave this year, we won’t be coming back”

It’s graduation season at schools and universities around the world, and the University of Waterloo is no exception.

I am part of the communications team for the Faculty of Mathematics, and graduation has been constantly on our minds since March: we had to update the website, plan videos and posts for social media, coordinate and staff the reception, and prep for the ceremony itself. In the last month, I’ve put together profiles of award winners and star students, written our dean’s convocation speech, and interviewed the brilliant and winsome mathematician Ian Stewart, who received an honorary doctorate this week.

After all of that work, however, the highlight of graduation for me - one of the highlights of my entire week - was the time I spent volunteering in the reception tent this Wednesday following the Computer Science graduation ceremony.1

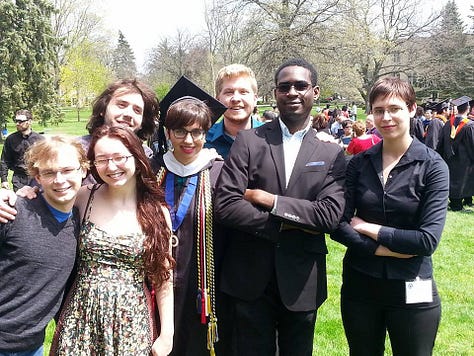

My job was to stand next to the photo background and help families get group photos of their graduates. I navigated the menus of phones in at least five different languages, held flowers and purses and jackets, adjusted gowns and sashes, and made faces in order to get babies to smile for the camera.

As I took photo after photo, patterns emerged: teenage sisters art directing, dads with fancy cameras getting shot after shot, shy graduates fiddling with their bright pink ties and enormous diplomas. I witnessed two moms whose sons were friends meet for the first time and warmly thank each other for their son’s friendship. I watched people get acquainted while waiting in line and then wish each other luck on their summer trips and new jobs. I said “Congratulation, doctor” to a PhD graduate wearing her velvet tam over her hijab and watched her face light up at her hard-earned title.2

As I took a few photos for each group, I tried to maintain care and attention for each one. In a job where graduation comes twice a year, it’s easy to forget that the photos I was taking might be shared with friends and relatives who couldn’t attend, treasured as a symbol of sacrifices and dreams spanning decades. I was having a great time, but I also found myself fighting tears again and again, looking at all these supporters from around the world united by their pride and love for their graduates.

Of the many things the Covid-19 pandemic stole from us, one of the most poignant was graduation. Though it doesn’t compare to the loss of life, financial deprivation, and social isolation that billions of people experienced, I know so many people who weren’t able to graduate in person from high school or university because of the pandemic. Though many institutions tried their best with virtual graduations featuring recorded messages of encouragement and digital slideshows, they were cold comfort, anticlimactic finales after years of hard work and struggle.

There really is no substitute for donning the unfamiliar cap and gown, marching down the aisle, hearing your name called, and posing for photo after photo after photo afterwards in the sunshine. Graduation might not be a matter of life-and-death, but it does matter.

Rites of Passage

We frequently refer to graduation - especially from high school and undergrad - as a “rite of passage” without thinking much about the term we are using.

“Rite of passage” is the English translation of a term introduced by folklorist Arnold van Gennep in his 1909 book Les rites de passage. Van Gennep argues that all human societies are divided up into social subgroups. Some of these groups - for example, children and adults - are biological in origin, whereas others - members of the clergy and laypeople, for example - are entirely constructed. Regardless, he says, people frequently transition from membership within one group to membership within another, and as such all human societies have developed ceremonies or traditions to mark and facilitate these transitions.

These traditions, or rites of passage, have three stages: separation, liminality, and incorporation.

The separation stage, explains anthropologist Victor W. Turner, “comprises symbolic behavior signifying the detachment of the individual or group either from an earlier fixed point in the social structure, from a set of cultural conditions (a ‘state’), or from both” (94). Often, this stage features symbolic alteration of the body, removal of clothing, or putting on of symbolic clothing. A new recruit in the military, for example, may receive a buzz cut, and trade his civilian clothing for a uniform.

In the case of high school or university graduation, this stage is usually the moment at which graduates put on their regalia, say temporary good-byes to their family and non-graduating friends, and line up among their classmates. Hair is checked, ties are straightened, and people fuss with each other’s unfamiliar robes, hoods, and hats.

Then comes the second, and to me, the most interesting stage of the rite of passage: the liminal stage. In this stage, the individual exists in a strange, in-between state, part of both social groups and neither at the same time. Often, this stage takes the form of a ceremony, administered by a well-respected member (or members) of the community, often one who already belongs to the category the individual will enter. Whether the individual is a drill sergeant training recruits, a priest conducting a wedding ceremony, or a village elder tasking an adolescent with a spiritual quest, the purpose is the same: to guide the individual through the ambiguous liminal space to the security of the other side.

In the case of graduation, of course, this stage is the graduation ceremony itself, with its march, speeches, words of advice, tearful songs, and so on.

Finally, the ceremony comes to the end, or vows are made, or a test is passed, and the individual ends the third and final phase of the rite: the incorporation phase. In graduation, this is marked by the moment that the graduate receives their diploma or their tassel moves from one side of their head to the other. As Van Kennep writes, this integration into a new social group is often commemorated by symbols of these “new ties”: thus “in rites of incorporation there is widespread use of the ‘sacred bond,’ the ‘sacred cord,’ the knot, and of analogous forms such as the belt, the ring, the bracelet and the crown” (166). For many graduates, these new ties are commemorated by a souvenir tassel, or a class ring, marking them as members of a new social group: alumni.

And then, of course, the community celebrates: with flowers, and parties, and cake, and stuffed animals wearing little hats, and - naturally - with photo after photo after photo.

When individuals don’t get to participate in these rites of passage, or when they participate in a rite that looks significantly different than they expected - for example, when graduation ceremonies were canceled or moved online due to the pandemic - they often report feeling caught indefinitely in that liminal space, experiencing feelings of anti-climax or incompleteness.

This is particularly important for a ritual like graduation - one of the few collective rituals left in our society. Many of our rites of passage - quinceaneras, weddings, retirement parties - focus on individuals or duos. To be a graduate, however, even as you are individually celebrated by your family and friends, is to be part of the class of something. Perhaps this is why people who were never close often grow sentimental as graduation draws near. Perhaps this is why the most famous graduation song for members of my generation is subtitled “friends forever,” despite the fact that graduates often were not friends prior to the ceremony, and certainly will not remain so after.

This group of people have seldom all been in the same space, and they will never be in the same space all together again - but they will, always and forever, be the class of 2011, or 2015, or 2024.

Valedictory

Both because graduation is a collective ritual that most people experience in some form, and because of its important symbolic weight, graduation ceremonies show up frequently in media, especially in Western media. If a TV or book series is set in high school or university, a graduation scene is nearly inevitable, allowing for characters to celebrate their accomplishments, reminisce with their friends, and consider the changes that lie ahead3

This week, I revisited the graduation episodes or scenes from several pieces of media set in high school, and discovered that despite their instantly recognizable shared trappings - caps and gowns, speeches, and future plans - their emphases were strongly tied to their overarching themes.

In Gossip Girl, students ignored the proceedings of their graduation ceremony to catch up on juicy updates delivered via their mid-2000s flip-phones.

In High School Musical 3: Senior Year, after an improbable sequence in which drama club members swayed and sang “We’re All in This Together” on a stage in full regalia while their university plans were spotlighted, the entire graduating class sang and danced to a raucous song called, appropriately, “High School Musical.”

And, in the two-part Buffy the Vampire Slayer season finale “Graduation Day,” the ceremony itself was an irritating time waster before the real rite of passage: the convocation speaker (the evil mayor of Sunnydale) transforming into a giant monster and trying to eat the students.

The most realistic graduation ceremony - and to me, the most moving - was this one, featured in Gilmore Girls.

Rory Gilmore is a bookish, studious person, and she and her single mother Lorelai work hard and make sacrifices for her to be able to attend private school (and later, to attend Yale University). Her graduation matters to her, and it matters to the show - as a ceremonial ending of this major chapter in her life, and as a vindication of Lorelai’s competence as a parent.

Graduation particularly matters to Rory, by the way, because she is the valedictorian of her graduating class: a fact repeatedly mentioned by her proud family and friends throughout the episode.

An unusually high number of fictional characters, by the way, are valedictorians - no doubt because, in an otherwise collective ceremony, the valedictorian’s speech provides an individual with the spotlight.

Not only does the valedictorian speech highlight an individual character’s accomplishments, but it also allows them to speak to - and on behalf of - their entire class.

In one of my favorite teen comedies, Booksmart, best friends Amy and Molly are dedicated, somewhat sheltered students excited to finish their last week of high school and head off to Ivy League schools. Despite being class president, Molly in particular is not very popular with her classmates, due to her condescension and somewhat sanctimonious attitude. At the beginning of the film, Molly sees her upcoming valedictory address as a reward, a chance to celebrate her superior approach to high school and impart her classmates with her well-earned wisdom.4

After a series of comedic misadventures, however, Molly and Amy learn to see their classmates as their equals: smart, funny, vulnerable, and deeply unsure of what lies ahead. In a raucous scene near the end of the movie, Molly bails Amy out of jail (it’s a long story) and the two of them race to their graduation in a borrowed car just in time for Molly to deliver a new, spontaneous valedictory address that better captures the spirit of her class.

“All I know,” she concludes, “is that we have a lot more to learn.”

Regalia

While the social and symbolic role of graduation may be evident, however, its particulars can be much more esoteric. Why do we use so many strange words - like “valedictorian,” for example? Why do graduates usually wear robes and hoods and strange flat caps? Why do we so often march in to “Pomp and Circumstance”?

The graduation ceremony that most of us are familiar with has its origins, like so many other aspects of culture, in Great Britain: specifically, at Oxford University and Cambridge University. Oxford and Cambridge are, respectively, the oldest and second-oldest continually operating English speaking universities in the world. Oxford’s founding date is unknown, but it dates back at least to 1096; Cambridge was founded by dissidents from Oxford in 1209.

The earliest universities occupied a social space at the junction of monasteries and guild halls: they were places of learning where students trained to be masters of their subject, and learning was conducted primarily in Latin. We owe a lot of specialized academic terminology to these Latin origins, including “valedictory” (“farewell”), “alma mater” (“generous mother”), and, for that matter, “university” (“society/guild,” or “the whole”)

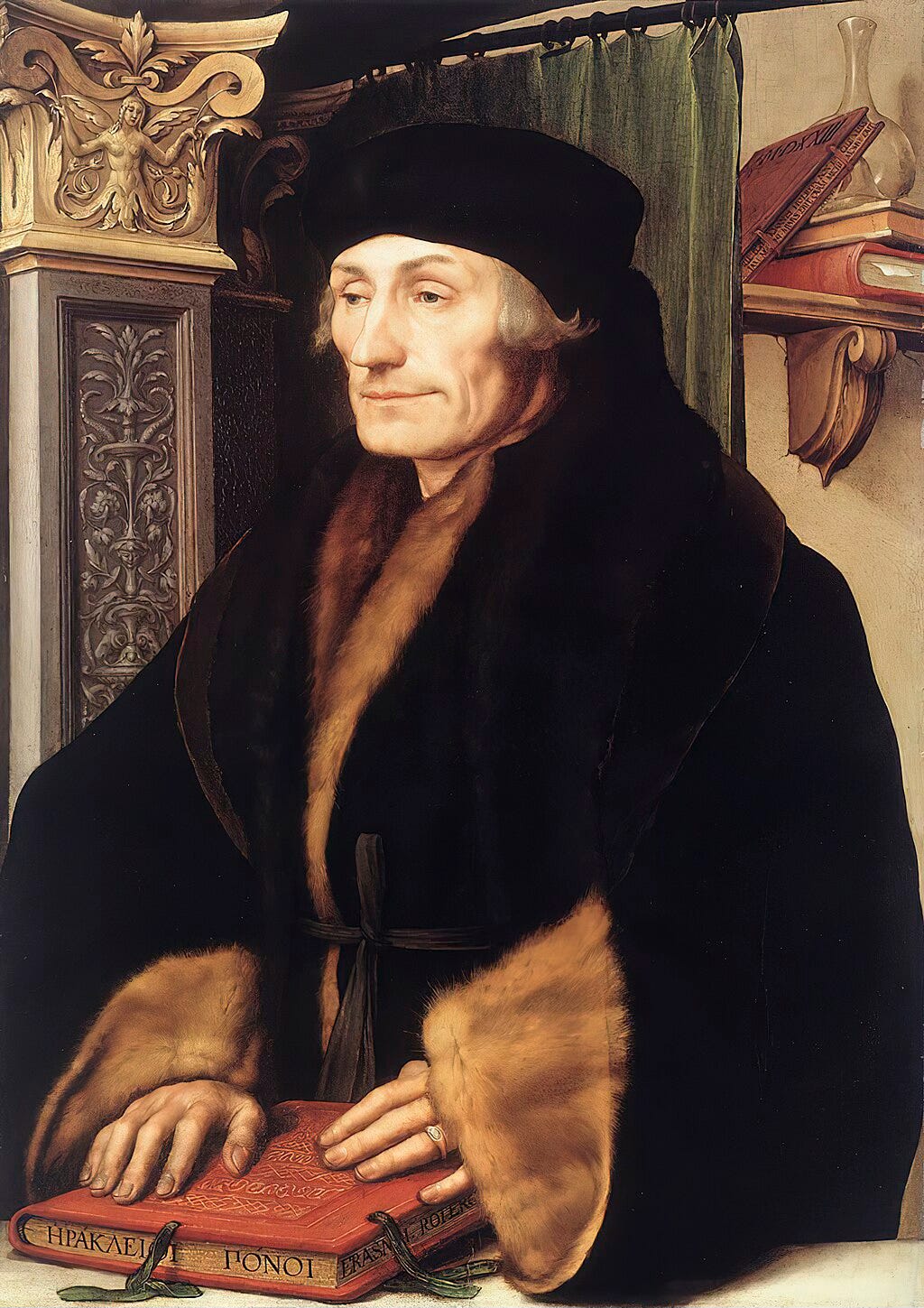

All scholars - both students and teachers - wore gowns full-time. These gowns were partially based on clergy robes, and they served both social and practical purposes. They set students apart from townsfolk, and they kept scholars warm during long periods of sitting and studying - early robes were often lined with fur, as seen in this 1523 painting of Erasmus of Rotterdam by Hans Holbein the Younger.

Gradually, the academic dress of Oxford and Cambridge became both standardized and regimented. Students and professors were expected to be in academic dress at all times; though standards relaxed gradually over the centuries, they still remain quite stringent in their places of origin. Students at Oxford University today don’t just wear their gowns and mortarboards during graduation: they also wear them during a matriculation ceremony at the beginning of the year, during important dinners and meetings, and during final exams - a far cry from the sweatpants and hoodies I wore to my finals in university!5

Those funny hats, by the way, are much more recent than the robes and hoods. Though it’s unclear when exactly mortarboards emerged, their predecessors are the pileus, soft velvet caps worn by medieval clergy. Over the first seven hundred years of Oxford’s existence, scholars wore a variety of soft silk or velvet caps, some featuring tassels. Today, graduates in non-English speaking countries still wear a variety of headgear, and PhD regalia frequently features a velvet tam or Tudor bonnet as further differentiation from undergraduate regalia.6

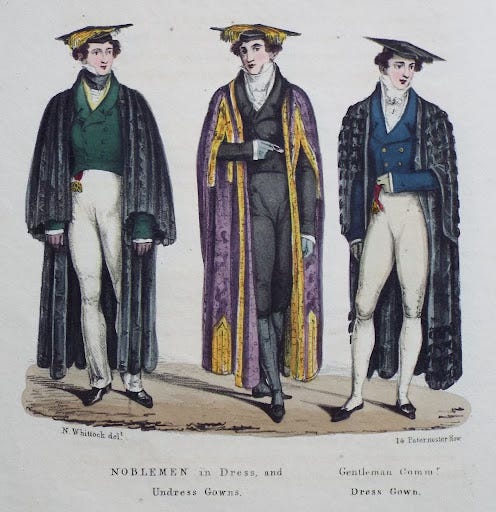

Mortarboards appear in England during the 18th century - legend dictates they are nicknamed “mortarboards” because their peculiar flat square tops resemble the boards used by bricklayers to hold mortar. You can see mortarboards and gowns featured in this Regency-era fashion plate depicting academic dress at Oxford: while the young men’s clothing looks historic, their regalia is instantly familiar.7

Of course, not everyone today wears a derivation of Oxford and Cambridge’s regalia - nor do they want to. The widespread wearing of caps and gowns, for many, speaks to the enormous and lasting impact of British colonization. Today, many individuals will add cords or sashes honoring their cultural heritage, and some countries have moved away from caps and gowns entirely in favor of a form of traditional dress. In 2019, the government of India requested that universities require saris for women and kurta or pyajama for men, preferably made out of fabric hand-woven in the country, instead of caps and gowns.

There are also practical reasons why graduates might not wear regalia. My favorite? Because they’re underwater.

In this clip, graduates of Singapore’s Naval Diving Unit graduate inside of a tank - dressed in full scuba suits, of course - while their family and friends look on from behind glass.

Pomp and Circumstance

One recognizable feature of graduation, by the way, does not stem from Oxford or Cambridge: “Pomp and Circumstance.”

For graduates in the United States, Canada, and the Philippines, “Pomp and Circumstance” is synonymous with graduation, but it’s much less common outside out of those countries. That’s because “Pomp and Circumstance” - the popular name for a section of Sir Edward Elgar’s “March No. 1 in D” (1901), from his larger “Pomp and Circumstances Marches” project, was first played at Yale University in 1905.

Yale music professor Samuel Sanford was personal friends with Elgar, and invited him to attend that June’s commencement and receive an honorary doctorate of music. To honor his friend, Sanford invited the New Haven Symphony Orchestra, the College Choir, the Glee Club, and both university and professional musicians to perform sections from Elgar’s works during the graduation ceremony. The most famous section, which we call “Pomp and Circumstance,” was actually played as graduates and professors marched out at the end of the ceremony, not in.

Even at graduation ceremonies where Elgar’s march isn’t actually played, the song’s shadow looms over the proceedings, suggesting through its title and solemnity the preferred tone for the ceremony. Graduation, after all, is a rite - with all the pageantry, effort, and seriousness that term implies. In a world that has become increasingly casual and unstructured, graduation ceremonies maintain a mysterious air of the antiquated, even the arcane, that imbues them with peculiar power.8

At the same time, however, graduation is also a time of exuberance and joy. One of my favorite examples of that joy is this reel from graduation at my alma mater, Andrews University, last spring. When the university returned to in-person graduation in 2021, graduates were not allowed to shake hands with President Andrea Luxton. Instead, they quickly developed a tradition of gesturing to the president, and she did her best to spontaneously return the gesture.

The reel went viral, and for good reason: it does such a wonderful job of capturing the buzzing energy and overflowing glee that you can feel in the air during a graduation ceremony. The few fuddy-duddies in the comments complaining that the graduates don’t respect the importance of the ceremony remind me, by negative example, not to get too caught up on details.

At the end of the day, it’s all just window dressing. What matters the most, in this shared rite of passage, is not the hat placement, or the music, or even the commencement speaker. I for one couldn’t tell you the content of the commencement address at any of my graduations.9

What we really remember are the ones who helped us reach that moment of transition, and were waiting for us cheering on the other side: the people in our pictures.

When it comes to graduation, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

The University of Waterloo is enormous - more than 42,000 students - and roughly 2,000 students graduate from the Faculty of Mathematics every year, so on Wednesday we held three graduation ceremonies: one for Computer Science, one for Statistics and Actuarial Science, and one for Pure Math, Applied Math, and Combinatorics and Optimization

It’s a truly great feeling. I sometimes joke that I did a PhD in large part to have a cool gender neutral title. It’s not a joke.

High school graduation is not nearly as big a deal in the UK as it is in North America.

I regret to inform you that, in my own high school valedictory address, my speech was very much along these lines, with a not-insignificant portion devoted to the importance of good grammar. A much more welcome resemblance? I have remained dear friends with the salutatorian, Amy.

Men only wear the hats outside, and are otherwise expected to carry them at their sides, in accordance with broader social norms regarding hat-wearing.

As someone whose terrible mortarboard placement earned her a spot in the “how not to wear your regalia” slideshow played during rehearsals for graduates at Andrews University, I was delighted and relieved to get to wear a much more comfortable velvet tam when I graduated with my PhD

Next time you’re rewatching Bridgerton, picture Anthony and Simon running around dressed like that during their wild student days. Not so sexy now, are they?

The seriousness of the ritual, by the way, is also why I hate the recent phenomenon of kindergarten graduation. I know, I know, it’s mostly just a photo op, and they look cute in the little caps and gowns, and I’m sure I’ll feel differently when my own kids do it, but I can’t escape my feeling that kindergarten graduation cheapens the power and meaning of the rite. In the words of Mr. Incredible, “They’re celebrating mediocrity!”

That does not mean, of course, that my desire to give a commencement address someday has diminished. I can at least do a better job than Harrison Butker.

Poignant. Glad that you’re still assisting in a University setting and experiencing the joys of other people’s graduations.