Song of the Week: “In the Aeroplane Over the Sea,” by Neutral Milk Hotel - “How strange it is to be anything at all”

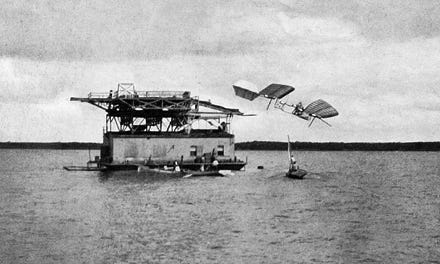

On October 7, 1903, Samuel Langley, the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and an accomplished astronomer, failed to build a working airplane.

With more than $50,000 of government grants and a series of successful glider tests, he had high hopes for his powered, manned airplane, which would be launched by a catapult over the Potomac River. The plane’s wing, unfortunately, got caught on the catapult during launch and it immediately crashed into the river, leaving its pilot unhurt and Langley embarrassed.

Two days later, the New York Times published an editorial mocking Langley and his fellow aspiring aviators for their aspirations of flight. “It might be assumed that the flying machine which will really fly might be evolved by the combined and continuous efforts of mathematicians and mechanicians in from one million to ten million years,” they proclaimed. “No doubt the problem has attractions for those it interests, but to the ordinary man it would seem as if effort might be employed more profitably.”

Two months later, of course, Ohio brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright took their first successful powered flights at Kitty Hawk.

In a speech in their hometown of Dayton five years later, Wilbur Wright observed that they were able to finally unlock the secret of flight when they realized that their flying machine would require both power and resistance. “In aeronautics,” he said, “we must have something to push against or we cannot go up. And in the game of life it is the same way.”

Frequent Crier

I don’t remember my first flight. I was around three years old, barely recovered from chicken pox, flying standby, miserable. What I do remember is that, for my entire adult life, I have cried on airplanes.

Now, to be fair, I am a frequent crier on the ground as well. I cry over Sufjan Stevens songs, roadkill, and this Tim Hortons commercial that ran during the 2010 Vancouver Olympics.12

But something special happens when I’m on a plane. Not all the time, mind you - sometimes I am exhausted and manage to just pass out for the duration of the flight. But if I am awake, and watching a movie, or reading a magazine article, or listening to music while looking out the window, or writing - I will usually shed a few tears.

I cried while writing topics for Syllabus - including this one! - in a notebook while I flew back from Colorado last year. I cried when I saw the first green hills of the North Island emerge from the fog last year on my flight to Auckland. I sobbed till I had to blow my nose while binge-watching season one of The Last of Us on a flight to Los Angeles.

[eight-year-old spoilers ahead]

Most memorably, however, on a 2017 flight from Denver to Toronto, I wept on and off for half an hour, overwhelmed by love for Taylor, excitement about the PhD offer I had just accepted at the University of Colorado Boulder, and a deep appreciation of the simultaneous beauty and horror of the world that lay below me.

The piece of art that inspired these revelations? Marvel’s Doctor Strange.

Specifically, the Ancient One’s death scene.

I haven’t rewatched Doctor Strange since that flight eight years ago, and I’ve never been that fond of the character. The fact that I watched the movie for the first time on a plane, instead of seeing it at midnight in theaters like other Marvel movies, tells you how invested in the story I wasn’t.

Rewatching that scene now - unlike the Tim Hortons commercial - I feel nothing. Out of context, in fact, it’s rather silly. Both characters are astrally projecting as ghosts, and they bob up and down gently throughout the scene like buoys in shallow water. They talk about channeling dimensional energy, and say things like “only together do you stand a chance of stopping Dormamu.3

And yet, as the Ancient One reflects on how mortality has given her work meaning, and then admits that she has stopped time just so she could watch the snow fall once more, I burst into tears. This movie, I thought, is one of the most profound things I’ve ever seen.

Perspective

As it turns out, I’m not alone in my propensity for crying on airplanes. In the segment “Contrails of my Tears” from a 2015 episode of This American Life, writer Brett Martin talks about how whenever he watches a movie on a plane, he ends up crying. It doesn’t matter what the movie is: Sweet Home Alabama, What a Girl Wants, Daredevil. His friend Lindsey cried to Freaky Friday without even having the sound on. Greg, a man he met at a party, got choked up over the ending of the famously terrible Dirty Dancing 2: Havana Nights.

“Let me be clear,” Martin says. “I am not afraid of flying. I like flying. And I’m not a crier, at least not on land. Like many men I know, even sensitive ones who know that having a cry can be healthy and good, I passed some invisible line in adolescence where I simply stopped doing it. There have been many times in life that I probably should have cried, actually tried to cry and wasn’t able to - because, of course, I didn’t happen to be at 30,000 feet.”

I’m not afraid of flying, either. I enjoy it: people watching at the airport, getting my tiny package of pretzels and can of ginger ale, tracking the progress of the plane on the little map. And, as I’ve established, I cry plenty on the ground.

A moment later, however, Martin identifies a plausible reason for our tears:

It was in Big Night, Stanley Tucci's movie about paternal love and Italian food. Midway through the movie, Tucci's character and his brother stage a feast in their New Jersey restaurant and at one point bring out a whole roast pig.

The camera pans across the faces of the guests, just amazed by this unbelievable bounty being wheeled into the room, and a lump began to rise in my throat. I found myself brimming over with joy, with the sense that somewhere in the darkness miles below, just like on the screen, people were laughing, communing, sharing a meal. It was impossibly beautiful, and there was just nothing to do but cry.

As Martin notes, being in an airplane is an entirely modern experience. For most of human history, travel happened at the speed of your own two feet, or a wagon slowly rolling down a rutted dirt road, or at best, on a galloping horse. And then, within the last century, we built astounding and improbable machines that allow us to board a metal tube in one city, rocket through the stratosphere at improbable speeds without any perspective or control over the experience, and then emerge in a different city, culture, and time zone.4

Airplanes are a liminal space - that is, a threshold, or “between” space - and as such, they often make us feel uneasy, unsettled, unmoored from our daily routines. We become anxious, irritable, or - occasionally - overcome with emotion.

In a 2010 travelogue video titled “I’m Not Going Down: Thoughts from Amsterdam,” John Green discusses his love for Amsterdam’s beauty and contradictions: maps of the Red Light District dominated by churches, ancient buildings perpetually under construction, and canal boats that manage to stay afloat despite being half full of water themselves.

As he walks, jet-lagged, along the cobblestone streets, he reflects that he is “grateful to be a little boat, full of water, still floating.”

Before John arrives in Amsterdam, however, he has to take three flights that gradually transport him from his hometown of Indianapolis to the Netherlands. His second flight, from Atlanta to Munich, is mostly miserable. He’s tired, his seat is uncomfortable, and the sleeping pill he takes to ease his transition across the Atlantic doesn’t work right, leaving him delirious in the airplane’s minute bathroom, staring bleary-eyed into the mirror. “I am like a tranquilized elephant,” he mutters. “I will not go down.”

And yet - despite the discomfort, despite the fact that his “mouth tastes like dead rat,” he is momentarily overcome by the beauty and profundity of flying. As he looks out the window at the sun rising at 36,000 feet, he marvels that “Until around a century ago, no one in human history had ever seen that.5

Aeronauts

As it turns out, John Green was only partially right about his observation that no one in human history had seen the view from 36,000 feet until a century earlier.

Humans have always dreamed of flight: civilizations from around the world have made art of birds in flight, told stories of flying gods and bird-men and magic enabling people to rise above the treetops and zoom from one place to another. In 1755, before anyone had flown, we find the first recorded use in English of the idiom “bird’s eye view,” implying that we had been dreaming for years of a shift in perspective.

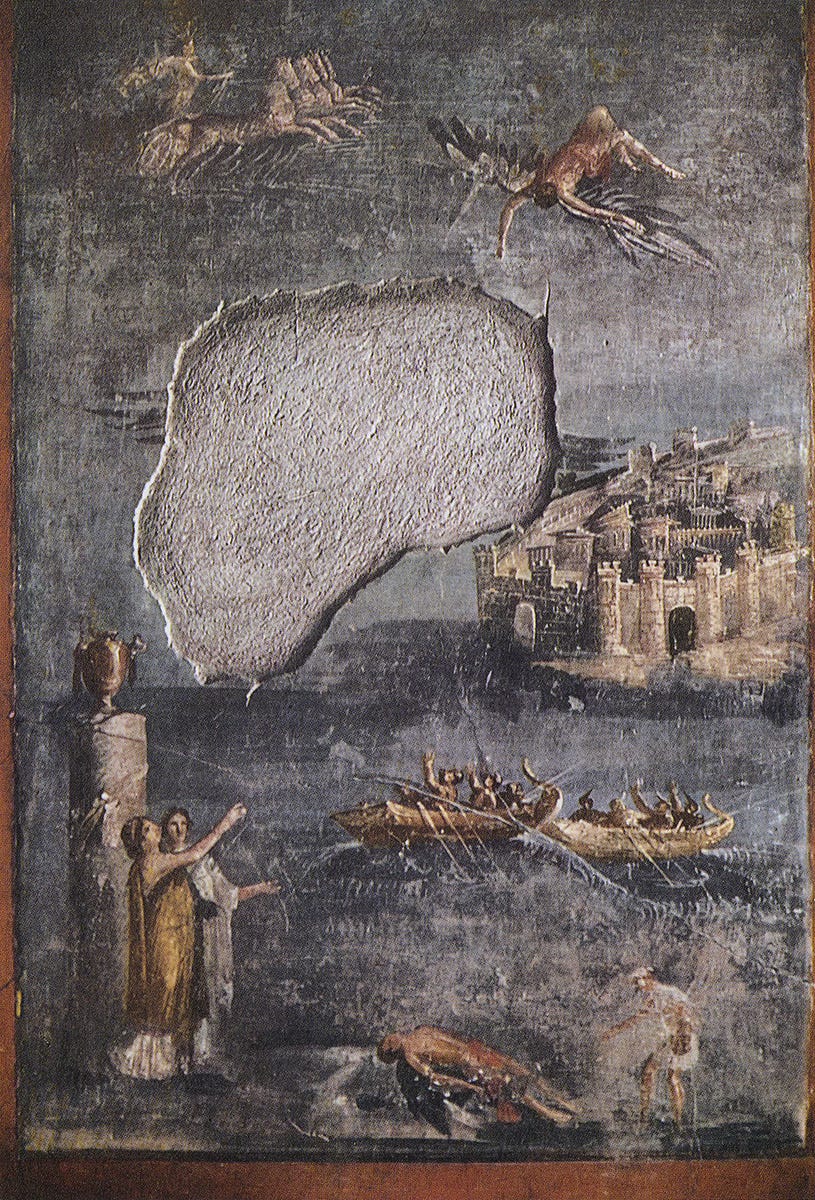

The most famous ancient story of attempted flight, of course, is the Greek legend of Icarus.

Icarus and his inventor father Daedalus had been imprisoned by King Minos, and Daedalus built them wings of birds’ feathers, wax, and leather to escape. He cautioned his son, however, not to fly too close to the waves below, lest his feathers become soaked, nor too close to the sun, lest the wax on his wings melt. Icarus, however, ignored his father’s warnings, dazzled by flight and the glory of the sun’s rays after so long in captivity. As his father looked on helplessly, the wax melted, the wings disintegrated, and he plunged to the ocean below where he drowned.

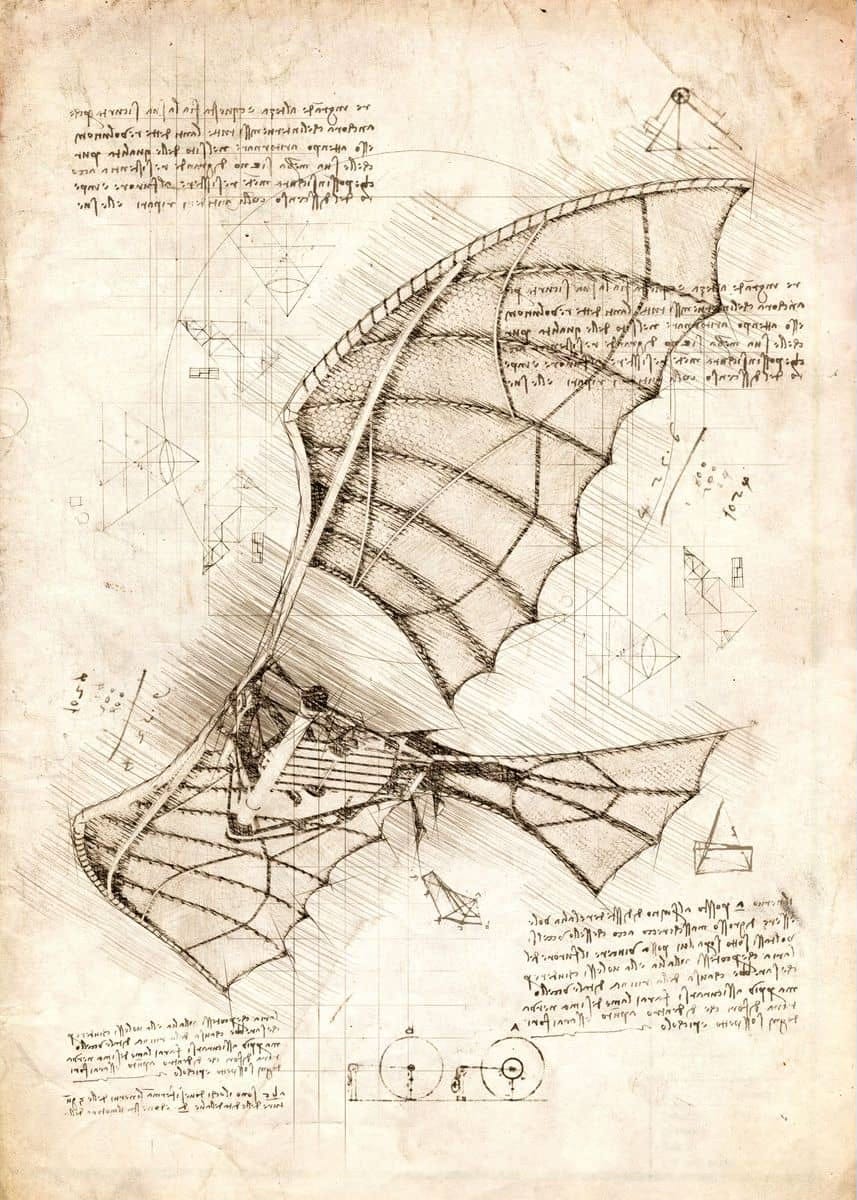

Centuries later, another inventor dreamed of flight - though he stayed safely on the ground. Leonardo da Vinci, the ultimate Renaissance Man, filled his journals with designs for proto-helicopters, airplanes, and other flying machines inspired by animals, plants, and the kites that traders had brought back from China.

He created over 500 sketches and wrote more than 35,000 words on the subject of flight, including one codex: Codice sul volo degli uccelli (Codex on the Flight of Birds) (1506).6 While we now understand that Da Vinci’s machines would not have worked, you can try your hand at piloting his ornithopter as he imagined it if you play Assassin’s Creed II!

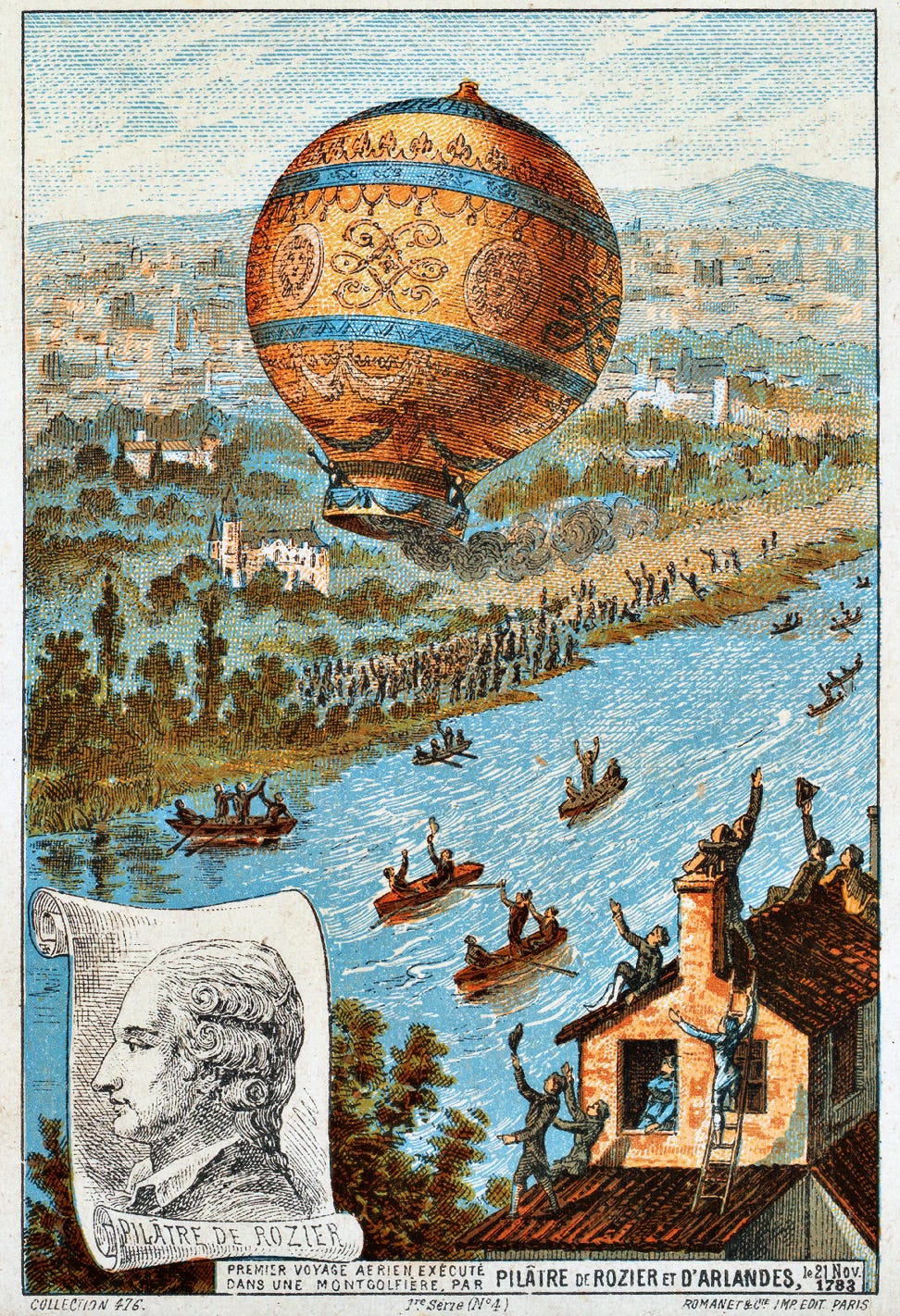

Two and a half centuries after Da Vinci’s death, however, his dreams were realized. Humans finally successfully took to the sky - and survived to tell the tale. Inspired by Chinese sky lanterns, French brothers Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier invented the first manned hot air balloon, and in 1783 two brave pilots took an eight minute flight from the grounds of Versailles Palace, rising to an impressive 1,500 feet before safely returning to the earth.

As was often the case in aviation history, the adrenaline-loving aristocrat Jean-Francois Pilatre de Rozier and his friend the Marquis d’Arlandes were the ones who actually first went up in the Montgolfiers’ balloon, not the Montgolfiers. The inventors of flying machines seldom piloted them, fearing that the frequent injuries and deaths resulting from testing their creations would cut their research short. And with good reason: de Rozier died in a hot air balloon crash eight years later, making him the first victim of an aviation accident in history.

In the century that followed, daring aeronauts tested the limits of humans’ capacity to take to the sky. Improvements in balloon technology and safety equipment allowed people to climb higher and higher, and in July 1901 - two years before Kitty Hawk - Arthur Berson and Reinhard Süring reached 35,000 feet in Streußen, an open-basket hydrogen-powered balloon equipped with oxygen cylinders. Remarkably, despite going numb from the below zero temperatures and temporarily losing consciousness, they both survived the flight, contributing to the discovery of the stratosphere and witnessing the same beautiful view of the earth that would inspire John Green more than a century later.

Kitty Hawk, of course, was not the end of humanity’s dream of flight, but the beginning: in the decades that followed, we would witness both horrors and wonders enacted by humans in flight. And we have flown ever higher.

High Flight

In 1966, three years before Neil Armstrong took his first steps onto the surface of the Moon, another famous spacefarer appeared on television screens for the first time: James T. Kirk, the captain of the U.S.S. Enterprise on Star Trek. Captain Kirk, played by Canadian actor William Shatner, began each episode by narrating the Enterprise’s mission to explore “space: the final frontier.”

In 2021, the then-90-year-old William Shatner finally got a chance to really go to space for himself, on a short Blue Origin flight. His experience in space profoundly moved him, in ways he did not expect. When he looked out the window for the first time into space, he recalls:

…there was no mystery, no majestic awe to behold…all I saw was death.

I saw a cold, dark, black emptiness. It was unlike any blackness you can see or feel on Earth. It was deep, enveloping, all-encompassing. I turned back toward the light of home. I could see the curvature of Earth, the beige of the desert, the white of the clouds and the blue of the sky. It was life. Nurturing, sustaining, life. Mother Earth. Gaia. And I was leaving her…I discovered that the beauty isn’t out there, it’s down here, with all of us. Leaving that behind made my connection to our tiny planet even more profound.

It was among the strongest feelings of grief I have ever encountered.

Last week, I flew from Toronto to Chicago to Austin, Texas to attend SXSW Edu, a conference for educators ranging from preschool teachers to higher-ed professionals like me. As I boarded my connecting flight, I was experiencing so many emotions at once: excitement for the conference and for Texas’s warm and sunny weather; anxiety about threats to education and intellectual freedom and the environment and democracy itself from the Trump administration; dread over Trump’s repeated threats to Canadian sovereignty.

By the time the plane took off, and the surrounding buildings and roads rapidly transformed into tiny points of light, I was - of course - crying. And then, through my tears, I typed out a message to my husband Taylor, which I knew would not be delivered till I had safely returned to the earth. Part of it read:

I always get emotional when I fly - how special, how improbable, that we have done this at all. How fragile and immense the world below: each tiny light representing a whole life.

Anyway, the plane was rising from Chicago to the clear dark sky, and I was thinking about how beautiful and terrible everything is at once - the cruelty and evil down there, but also the creativity and love and joy. Feeling this sense of not knowing what was ahead, but a calm resolve to face it, as so many people before me have faced terrifying and terrible things, without even having the sight of a million lights twinkling like fireflies or stars below them to give them courage.

And I was thinking about how the world is impossibly large, and I am impossibly small in it, and there probably isn’t much I can do to change it one way or another, when you realize how big it is. But also that the world is so vast and full of people, and how incredibly improbable with all of those people that I managed to find you in it, and that you’re down there right now, watching TV and eating dinner and loving me back. And how lucky I am, to be alive at the same time as you, to get to fly on planes and see stars and drink airport gin and tonics with olives, and love you.

I don’t know what’s ahead, whether I’ve got five years left or fifty, but I’m just immensely lucky to have been here and now.

I was crying, no doubt, for many reasons, but most of all, I was crying from gratitude.

On December 11, 1941, 19-year-old Royal Canadian Air Force pilot John Gillespie Magee Jr. was killed mid-flight during a combat training exercise. Three months before his death, however, he sent his parents a letter which included a sonnet he had written, which his father - a minister - printed in several church publications.

That sonnet became the official poem of the Royal Canadian Air Force, and the British Royal Air Force. When President Ronald Reagan addressed the nation following the horrific explosion of the Challenger space shuttle in January 1986, he quoted from that poem.

It’s called “High Flight.”

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings; Sunward I've climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth of sun-split clouds,—and done a hundred things You have not dreamed of—wheeled and soared and swung High in the sunlit silence. Hovering there, I've chased the shouting wind along, and flung My eager craft through footless halls of air... Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue I've topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace Where never lark, or even eagle flew— And, while with silent lifting mind I've trod The high untrespassed sanctity of space, Put out my hand, and touched the face of God.

When it comes to crying on airplanes, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

I don’t even like Tim Hortons that much. But it was late when I saw it, and I had strep throat, and my mother’s family immigrated to Canada, and the coats he buys his kids are so small! And yes, I did cry again while rewatching it for this Syllabus.

I’m not alone in crying over this one either - in a blog post, the commercial’s art director Winston Lee Chan reflects that “Welcome Home” is one of the projects he is most proud of, and resonates with many Canadians’ story of being immigrants.

Don’t worry, Doctor Strange fans, I’m perfectly aware that my favorites like Lord of the Rings often seem just as absurd without context. That is the gift and the curse of fantasy and science fiction.

Time zones were only invented after the creation of the railroad system, which allowed people to travel fast enough between communities stretched across a long distance for the difference in time to affect them.

Two years later, in his novel The Fault in Our Stars (2012), John Green gives his character Augustus Waters more open enthusiasm for the view on his own first flight, a direct flight to Amsterdam from Indianapolis. “We are flying,” Augustus declares. “NOTHING HAS EVER LOOKED LIKE THAT EVER IN ALL OF HUMAN HISTORY” (145).

I’m going to pay more attention to how I feel when I fly from now on.

I was at Lee Valley just before this came out and was admiring a kit to build a mini version of Da Vinci's ornithopter! Movies really hit different on a plane :p Though I expect I'd have sobbed to Inside Out 2 on the ground as well :p