Song of the Week: “Riddle Song,” by Doc Watson - “How can there be a cherry that has no stone?”1

July, when I was a kid, meant the Cousins Birthday Party: a full day extended family celebration of all of the young cousins’ birthdays at once. We would gather at my Aunt Rosemary’s house to spend hours in the pool, decorate cupcakes, and open gifts. For me, however, the highlight was the treasure hunt. After impatiently spending an hour of precious sunshine cooped up in the basement, we would be released in teams of two to solve riddles on color-coded slips of paper that led us through fields, under rocks, between berry bushes, and into the mailbox. In my memory of it, at least, my cousin Heidi and I always won, propelled to victory by my deep love of puzzles.

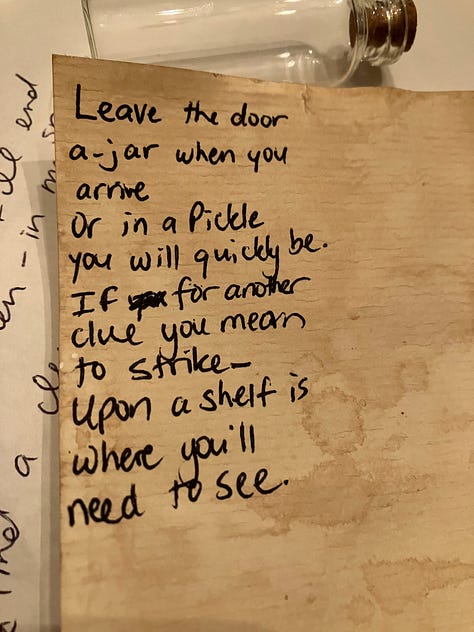

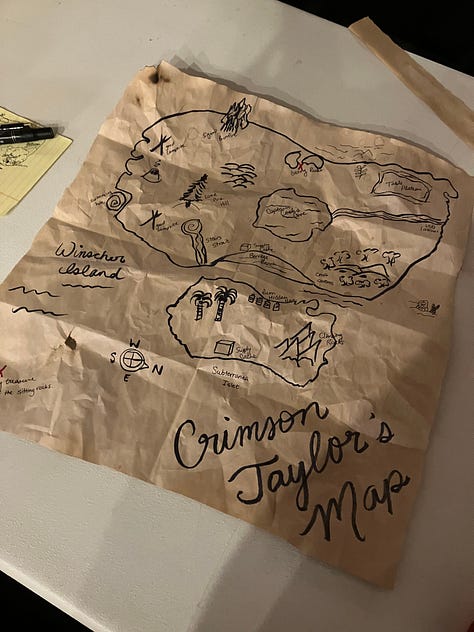

Over the years, the Cousins Birthday Party diminished; one of my mom’s sisters moved too far away to drive up every summer, and big family parties were traded for more subdued dinners and gift cards on our actual birthdays. But my love for treasure hunts endured. Two years ago, Taylor and I bought our nieces and nephew a book about pirates for Christmas, and created a treasure hunt for them to go with it: we crafted an aged map that transformed their grandparents’ house into a mysterious island, and throughout the house we hid tiny glass bottles filled with rhymed clues written on parchment.

You could have heard the shrieking and pounding of feet the next town over: for half an hour the three of them ignored their screens in favor of racing at breakneck speed around the house, deciphering our riddles and peering behind knicknacks. Finally, hidden in the body of an ornate clock, they found their treasure: a chest filled with personalized “piratey” necklaces I made them, and a generous heap of shiny chocolate loonies and toonies.2

I love puzzles of all kinds, of course: jigsaw puzzles, crosswords, video games like Chants of Sennaar that test your wits more than your reflexes. But I have a special affection for experiences that combine puzzles with themes or narratives and turn them into something social, propulsive, exciting: a category of activities that a creative group of folks over on Reddit collectively term “constructed adventures.”

Immersive Theater

Silly and uncritically patriotic as it may be, I love National Treasure (2004), which follows Benjamin Franklin Gates (Nicholas Cage) and his friends as they attempt to find a treasure hidden by the Founding Fathers. Armed with an encyclopedic knowledge of American history and a knack for puzzles, their adventures take them from the Arctic to the Smithsonian, as they crack ciphers, decode riddles, and look for a possible treasure map on the back of the Declaration of Independence.

As absurd as National Treasure is, I love the way that the movie - like Indiana Jones before it - captures the thrill of solving a really good puzzle. After staring at what seems like incomprehensible nonsense, suddenly something clicks, and you feel like the cleverest person in the world.3

For most people, the closest that they’ll come to National Treasure is doing an escape room. Escape rooms, despite being a relatively modern phenomenon, need little introduction: in the last twenty years they’ve popped up everywhere, with more than 50,000 escape rooms worldwide. If you haven’t tried one yet, the premise is simple: a group of people (usually 4-8) work collaboratively to solve a series of puzzles within a themed environment, usually in a tight time frame. Whether you’re looking for combinations for simple locks, or interacting with elaborate special effects, the best escape rooms combine puzzles with storytelling elements to create immersive narratives that make you feel like a character in a movie or video game. This isn’t a coincidence: the first proto-escape room, “True Dungeon” created in 2003 by Jeff Martin for GenCon Indy, was inspired by video games and Dungeons & Dragons.

Our first escape room experience was a particularly unique one. Playing against two other teams, we had to find the codes for a series of locks on our assigned treasure chest, all while actually cruising Hamilton Harbour on a real boat decorated to look like a pirate ship! My favorite puzzle involved throwing a bucket tied to a rope over the side of the boat and pulling up lake water to extract a key hidden inside the treasure chest.

Returning to dry land victorious, skull-and-crossbones medallion around my neck, I knew I was hooked. A couple months later, we did another escape room experience from the same company - a creepy nighttime hunt at Black Creek Pioneer Village - and won that too. A series of more traditional escape rooms followed, each of them wonderful: a cold war spy vs. spy room that I cracked with my team at work; an investigation of a tomb beneath the Sphinx that my friends did last weekend; and best of all, an alien invasion that we unmasked as part of Taylor’s birthday celebrations last year.

Most people think about escape rooms primarily as intellectual exercises. Haley ER Cooper, however, argues that the difficulty of the puzzles isn’t really the point. Cooper is an expert on immersive theater, which includes both nontraditional theatrical productions as well as escape rooms. Escape rooms, she argues, are just as much about engaging with other people in the real world as they are about intelligence or problem-solving. “Escape rooms…give us our bodies back,” she writes “Too often we chain ourselves to chairs to stare at screens - we might as well be those brains in vats. But escape rooms don’t come with seats. You’ll need your hands, feet, and knees to find the clues…The tactile experience adds immeasurable value.”

One example? At the Ancient Egypt-themed escape room we did last weekend, we discovered a carving depicting priests performing a ritual around the recently-mummified pharaoh. After a moment, we realized we’d have to replicate it: Taylor and Andy stood on either side of the empty sarcophagus in the middle of the room with their arms outstretched, and Jillian climbed in, triggering the next phase in the puzzle a moment later!

Enigmatologists

For some people, however, the intellectually punishing puzzle solving is the point: and for those people, there are puzzle hunts. Much as in escape rooms, teams work together to solve a series of obscure puzzles - this time over the course of a weekend or week. The first and most famous puzzle hunt, unsurprisingly, comes from MIT: the annual MIT Mystery Hunt was created by graduate student Brad Schaefer in 1981, and today attracts more than 3,000 participants from around the world. Unlike tactile escape rooms, these puzzle hunts often happen partially or completely online, and the individual puzzles frequently take hours, not minutes, to solve.

Recently, I got to be part of creating a puzzle hunt at the University of Waterloo. Math professor and “chief enigmatologist” Ty Ghaswala had been a huge fan of the puzzle hunt at his alma mater, the University of Melbourne, so three years ago he created a small puzzle hunt for math students called “Key Clues.”4 It was a big success, and opened up the following year to faculty, staff, and students across the university. The participants, however, were still mostly from math, despite the fact that the puzzles didn’t require mathematical knowledge to solve.

Enter my coworker Elisabetta and I. We volunteered to create a theme and story for Key Clues, eventually settling on a Hitchcock-inspired narrative about lost archives and forgotten secrets. We created a viral marketing campaign that blanketed campus with mysterious posters featuring a shadowy figure and the words “You have forgotten too much.” We planted cryptic messages in the student newspaper. And, perhaps most importantly, we told literally everyone we encountered to sign up. It worked: more than 700 people on 130 teams from across the university signed up to play.

Seventeen volunteers crafted the puzzles that went out last week to those teams. Despite my love for puzzles, I only helped write one: a puzzle called “Tragedies,” which you can try your hand at here, if you’re curious. Most of the time, I was busy transforming that collection of puzzles into a satisfying story about an ominous figure named “The Watcher” who lurked just out of sight, toying with the player’s mind.

I spent days tramping all over campus with a paper map and notebook in hand, taking note of anything interesting or strange I could find. I climbed stairs, explored tunnels, talked to museum curators, and called librarians, and used what I learned to craft a sequence of eighteen “chapters” that together told a story about what our society remembers, and what we choose to forget. It was, by far, the most fun thing I’ve ever gotten to write for work.5

Storytelling, it turns out, comes much more easily to me than puzzle crafting.

Meaningful Worlds

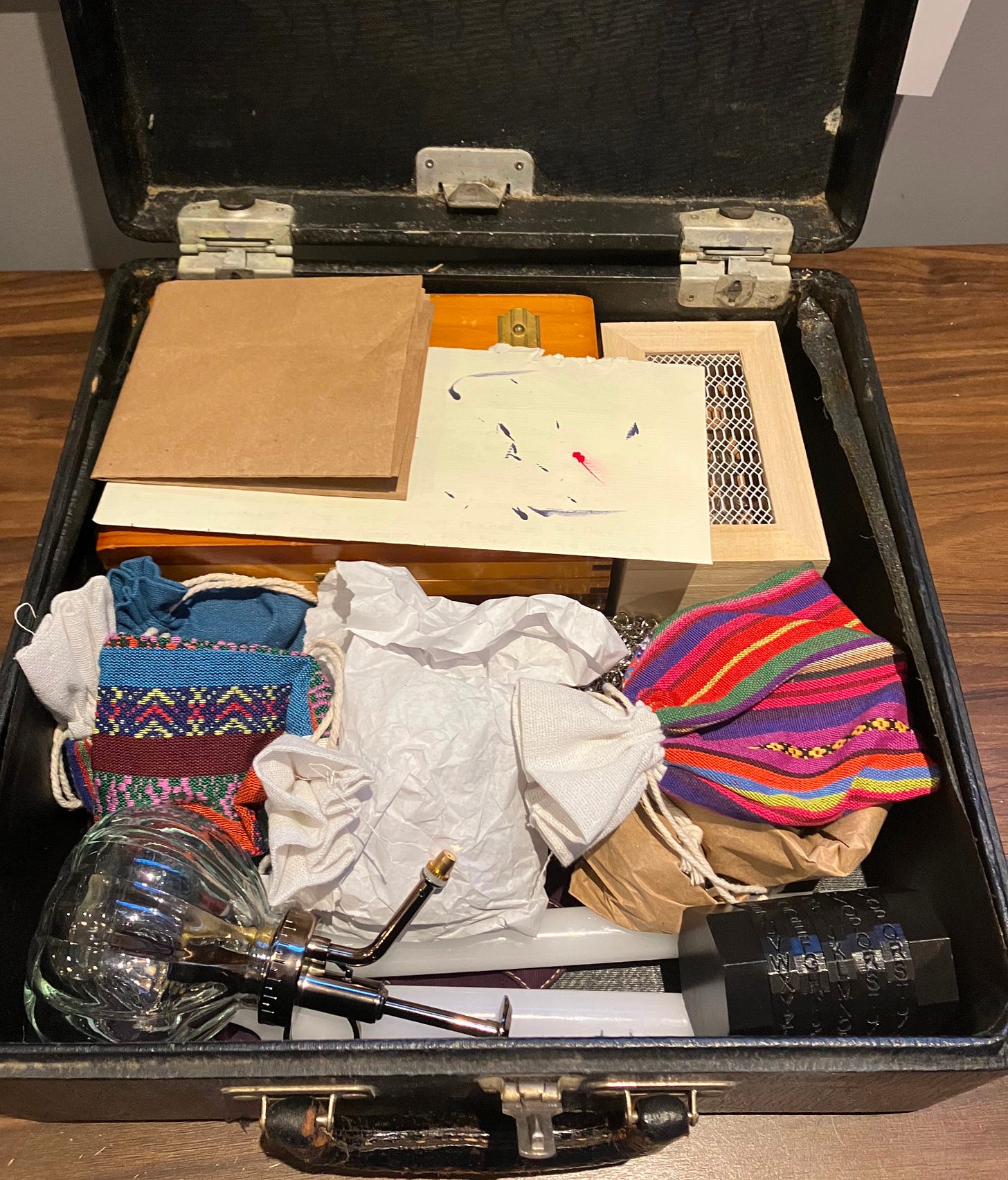

Two and a half years ago, before I had ever completed an in-person escape room or even heard of puzzle hunts, I decided to create an “escape room in a box” for my friend Jillian’s thirtieth birthday. I presented her with a mysterious package containing a sealed letter and the personal effects of a suspected witch who lived on the edge of a fantasy village. There was a box of strange substances in cryptically labelled jars, bags containing souvenirs from far-off lands, a 3D printed cryptex, an annotated map, and - the piece de resistance - a leather notebook filled with drawings, spells, and journal entries. With the advice of the fine folks at r/constructedadventures, I constructed three (I thought!) simple puzzles, whose solutions would together give her the passcode to the cryptex.

As it turns out, puzzle construction is way harder than it seems! Jillian cracked my cipher without even needing the key I had hidden in the notebook’s pages, then spent hours increasingly frustrated by the other two puzzles. Though, with hints, she eventually opened the cryptex, the fault for her struggles was all mine: I had gotten so carried away creating props and spinning a story of lost love that I accidentally created hundreds of red herrings that made my puzzles much harder to solve!

Nevertheless, she loved the gift, because she understood that at their best, constructed adventures are expressions of love. In a world of intellectual laziness and willful ignorance, they reward critical thinking and persistence. In an era when we spend so much time alone staring at screens, they encourage us to spend time with each other, and work together. They are a celebration of creativity and imagination and play.

Creating puzzle hunts and escape rooms and treasure maps can seem frivolous at best in a time where it feels like the world is falling apart. But in a moment where cruelty is celebrated and chaos rules the day, created adventures insist on the importance of thoughtfulness and craftsmanship and meaning.

Even the little puzzle I’ve created for you here.

When it comes to constructed adventures, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

A popular Appalachian folk song, “Riddle Song” dates back to 15th century England. I first learned it from Song of the Unicorn, a Classical Kids CD about Medieval music.

Canadians call our one dollar coins “loonies” because they have loons, a kind of bird, pictured on them. We call our two dollar coins “toonies” because they’re worth two loonies. We are not a serious people.

In the case of Indiana Jones, often something literally clicks, and then 1-4 hapless extras die horribly.

Fun and somehow unsurprising fact: the University of Melbourne’s puzzle hunt was co-created in 2004 by WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, who was a student at the time. Apparently he got bored with existing puzzles and decided to move on to something more challenging.

If you’re curious, you can click through the hunt and see all the puzzles, solutions, and narratives now that it’s finished. The prologue is currently listed on the “Story” page below the epilogue and a Q&A with me, and the narrative “chapters” accompany each puzzle on the “Puzzles” page.

I will attempt later, but for now, WOW! Way to engage the student body and even some old folk like me.

I'm very sleep-deprived and handed this to Andy to solve the puzzle, and he got it very quickly and revealed it to my sleepy brain. I agree wholeheartedly.