Song of the Week: “First Train Home,” by Imogen Heap - “I want to run in fields, paint the kitchen, and love someone”

Last month, my dad texted me to tell me that he and my mom were finally redecorating my bedroom in their house.

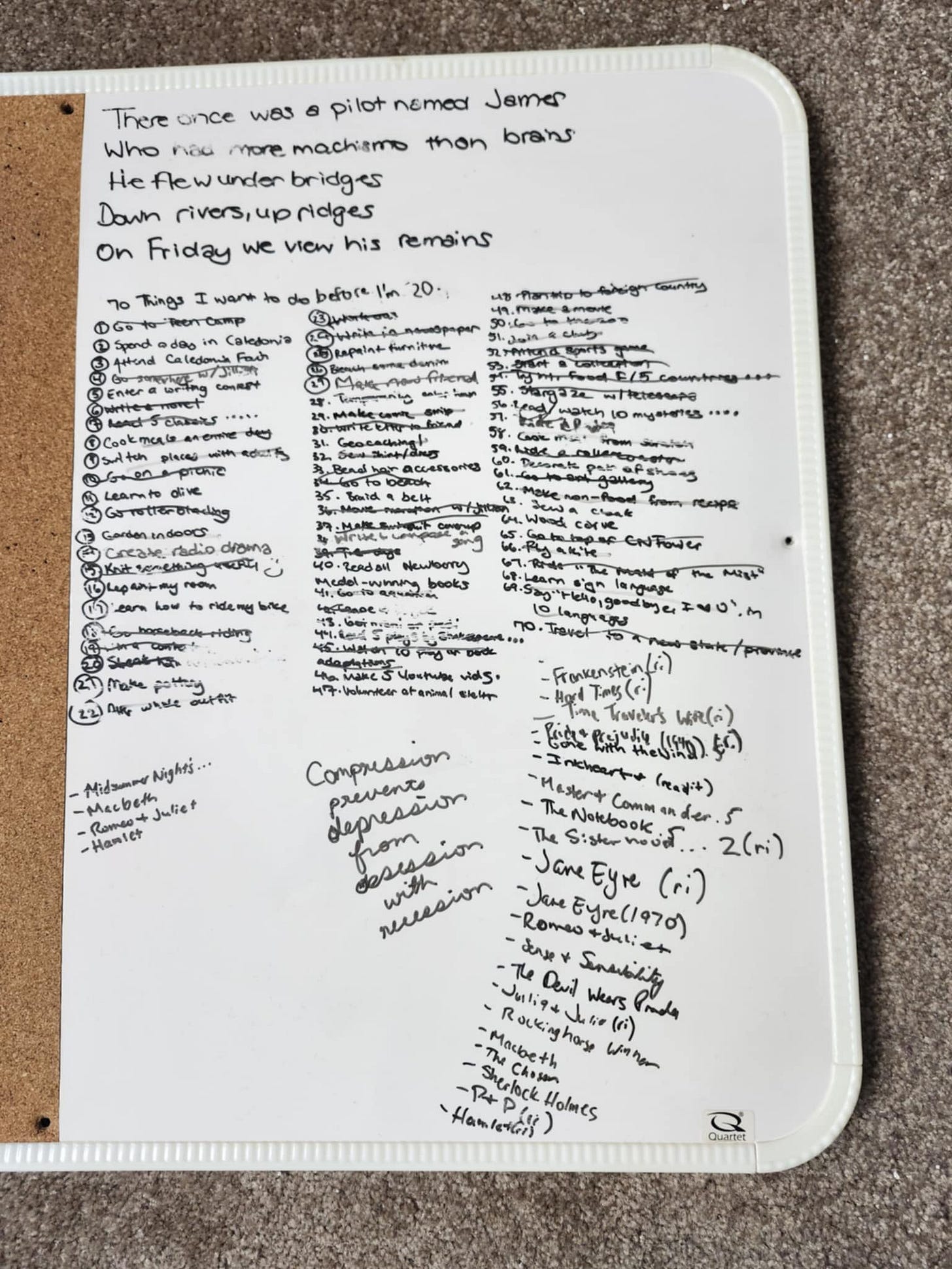

This was not an upsetting text to receive; my parents bought that house the same year I started graduate school, and I only lived in it for a couple of years. My dad told me they would be getting rid of the ugly red curtains that came with the house, the beige walls, and the free posters I had taped up next to the bed in a half-hearted effort to give the room some personality. One thing, however, he was saving: a combination corkboard/whiteboard that had somehow survived multiple moves from its original place in my actual childhood bedroom. On it was an ambitious list: “70 Things I want to do before I’m 20.”1

I must have been 14 or 15 when I made this list: I had already met my best friend Jillian (mentioned in items 4 and 36) but - based on the amount of free time I was trying to fill - I obviously hadn’t yet left home for Kingsway College, the Adventist boarding school I attended for grades 11 and 12.

Seventeen years later, I read the long-abandoned list out loud to that same best friend, and we laughed and reminisced over its contents. Some goals were hilariously dated: “switch places with adults” and “cook meals an entire day” are simply a regular feature of grown-up life.

Others, we were delighted to realize, I had failed to achieve before 20, but had eventually done anyway: I took a wood carving class with Jillian last February, sewed a wool cloak during the pandemic, and went geocaching multiple times with Taylor after we started dating. One item stood out as fodder for teasing: #17, “learn to ride my bike.” I’m thirty-one years old, and I still can’t ride a bike.2

Mostly, however, I was happy to realize that the person I was as a teenager is still so similar to the person I am today. I still love trying new and interesting things, but more importantly, I still love checking them off of a list.

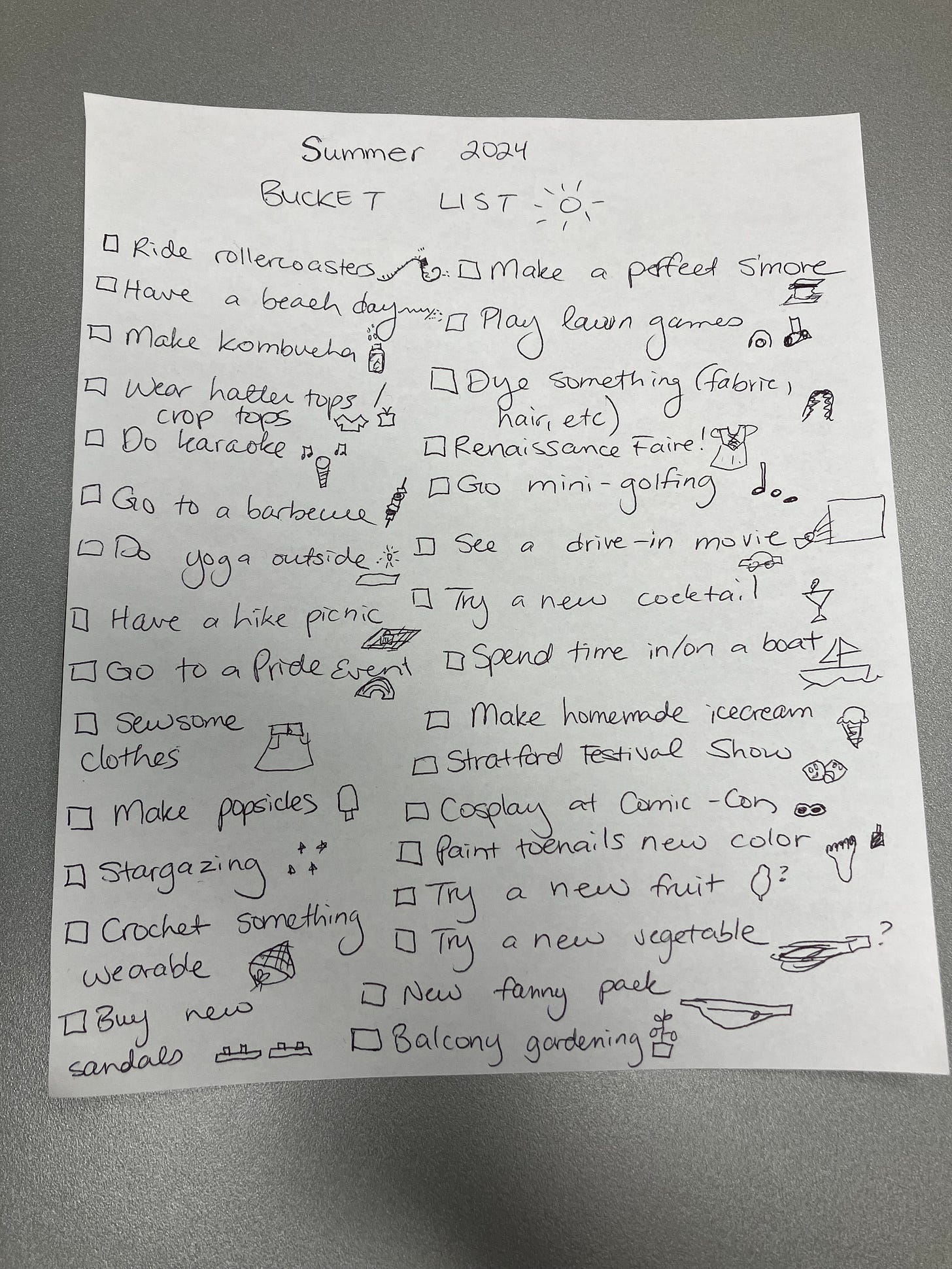

Last April, I saw a TikTok declaring that the reason summers don’t feel as long and exciting as adults is because we don’t fill them intentionally with the kinds of seasonal activities that we did as teenagers. Inspired, I decided to make an old school, doodle-filled “summer bucket list,” outlining 31 things I wanted to do that summer.

Some things were small: I wanted to try a new fruit, and do yoga in the field outside my apartment building. Others were much bigger undertakings, like putting together a cosplay for Toronto Fan Expo or spending time on a boat.

Some items, such as attending a Pride event or trying a new cocktail, would have been alien to the girl I was at 14. But other items appeared much the same as they had sixteen years earlier: every summer, it seems, I decide I’m suddenly going to start sewing my own clothes.

There was one other thing, though, that 14-year-old me probably wouldn’t have recognized about last summer’s list: the term “bucket list.”

Justin’s Bucket List

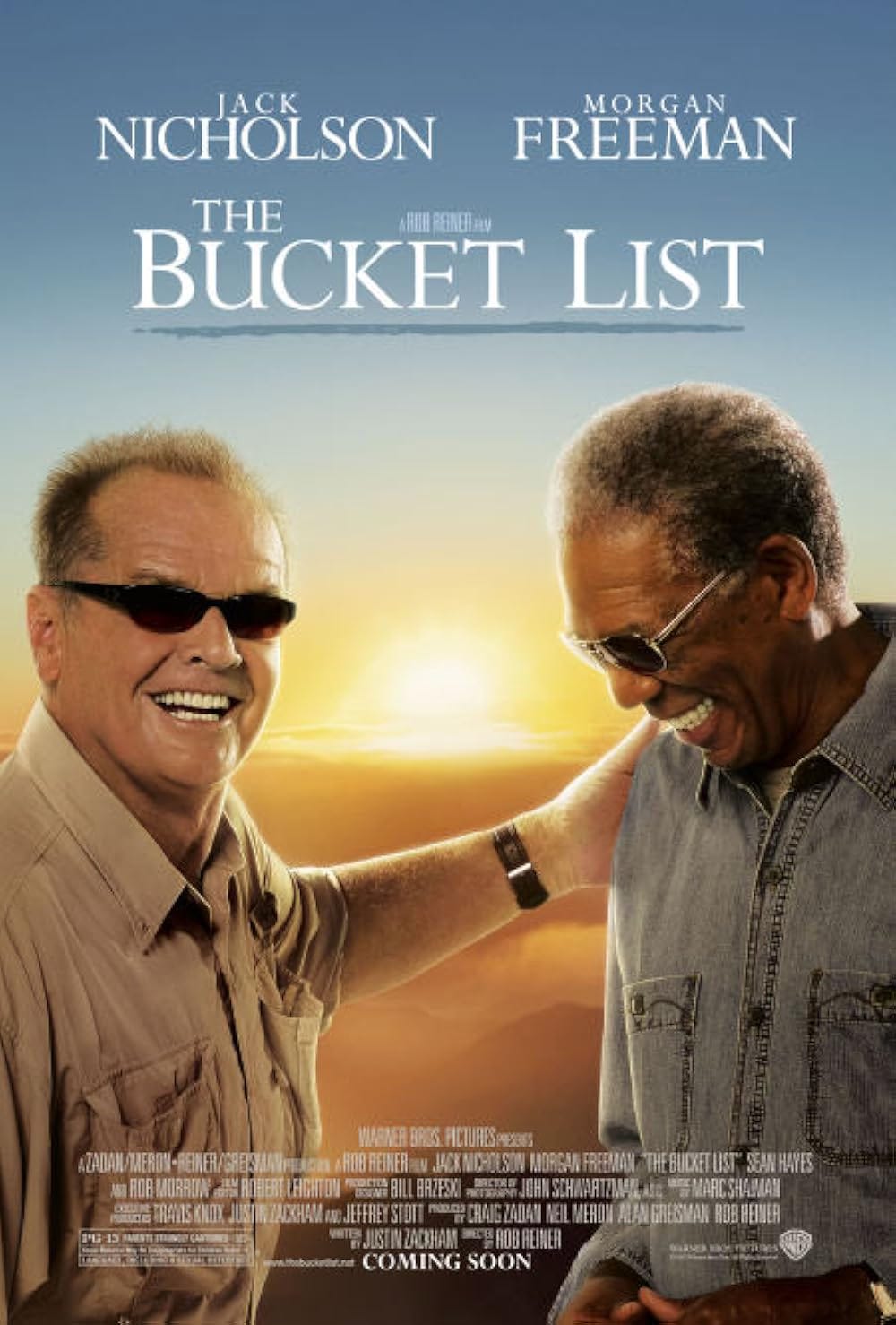

In 1999, the writer Justin Zackham sat down at his desk and made a list of things he wanted to do before he died, including “meet the perfect girl,” “go skydiving,” and “have a movie made at a major Hollywood studio.” He titled it “List of Things to Do Before I Kick the Bucket,” then shortened this title to “Justin’s Bucket List.”

Within just a few years, he checked off several things on that list: most famously, he made a movie with legendary director Rob Reiner about two men with terminal cancer (played by Jack Nicholson and Morgan Freeman) who break out of the hospital together and take a whirlwind trip around the world. That movie was, of course, called The Bucket List (2007).

The movie itself has largely been forgotten: critics thought it was schmaltzy, with Roger Ebert (who lost his lower jaw to cancer the year before) complaining that the movie “thinks dying of cancer is a laff riot followed by a dime-store epiphany.”

Much more importantly, however, The Bucket List gave us the term “bucket list”: a term that has become so ubiquitous, in fact, that people refuse to believe it didn’t exist prior to the 2007 movie.

Part of the reason why it’s hard to believe the term “bucket list” is a recent invention is because it perfectly labels a category of lists that already existed. In 2003, for instance, Patricia Schultz published a book she had been working on since 1995 called 1,000 Places to See Before You Die. The subtitle? “A Traveler’s Life List.”

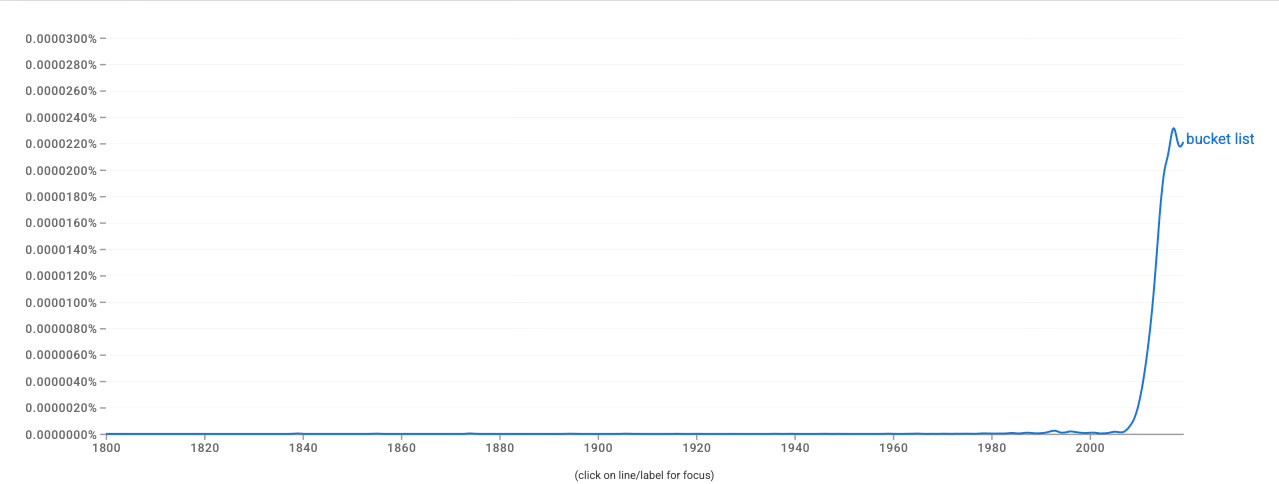

Despite multiple claims from redditors that they remember making bucket lists decades prior to the movie (ironically enough, in the Mandela Effect subreddit), there is no proof that the term was widely used prior to Zackham’s movie. Take, for example, this Google Ngram graph, charting mentions of the term “bucket list” in literature from 1800 to 2019.

Nevertheless, the term spread quickly. As the Oxford English Dictionary notes, by 2009 an article in the New York Times describes a trip to the Galapagos Islands as being on a traveler’s bucket list. A year later, Stanley Tucci’s character in the teen comedy Easy A gleefully announces that after he watches The Bucket List he can “cross “watch the Bucket List” off our bucket list” - implying that the term had already become culturally distinct from the movie by 2010.

Soon, people were using “bucket list” in the same general way I would use it last summer: to refer simply to a list of things to accomplish within a set period of time, not necessarily before death. In his appearance at the 2015 White House Correspondents Dinner, for example, Barack Obama talks about a staffer asking him if he has a “bucket list” of things to accomplish before he leaves office. Well, he smirks, “I have a list of things that rhymes with ‘bucket.’”

It’s too bad that Zackham didn’t have “be cited in the Oxford English Dictionary” on his bucket list.3

His Imminent Death

[spoilers in this section!]

One of my favorite movies of all time, Stranger Than Fiction (2006), is about a boring, emotionally closed-off IRS agent named Harold Crick who begins to hear a British woman’s voice narrating his life. Harold, it turns out, is a character in a novel that famously cynical author Karen Eiffel is currently writing.

At first, Harold thinks he is going insane, and attempts to rid himself of the voice while continuing to go about his orderly business. Things start to change, however, when the voice matter-of-factly states “little did he know that this simple, seemingly innocuous act would lead to his imminent death.”

Unsure as to how much time he has left, Harold begins to do new things that take him out of his routine. He eats warm, homemade chocolate chip cookies for the first time. He buys an electric guitar and learns to play. He falls in love with a punk rock baker whose business he’s been assigned to audit.

As he does these things, of course, Harold’s life transforms. He opens himself up to the world. He makes friends. He notices how extraordinary ordinary life can be. And - even though he realizes he does not want to die - he accepts his mortality.

Ultimately, Karen Eiffel decides to change the ending of her novel - even though it lessens its artistic value - and spare Harold’s life, moved by the way that she’s seen him change and grow. Harold is still badly injured in a bus accident, but he is able to recover thanks to the love that now surrounds him. In the film’s final moments, the newly hopeful Eiffel narrates:

Sometimes, when we lose ourselves in fear and despair, in routine and constancy, in hopelessness and tragedy, we can thank God for Bavarian sugar cookies. And fortunately, when there aren’t any cookies, we can still find reassurance in a familiar hand on our skin, or a kind and loving gesture, or a subtle encouragement, or a loving embrace, or an offer of comfort. Not to mention hospital gurneys, and nose plugs, an uneaten danish, soft-spoken secrets, and Fender Stratocasters, and maybe the occasional piece of fiction.

And we must remember that all these things - the nuances, the anomalies, the subtleties - that we assume only accessorize our days are in fact here for a much larger and nobler cause: they are here to save our lives.

Before I sat down and made that bucket list last summer, of course, I was already living a far more varied and vibrant life than Harold Crick. But I was also very busy: busy dealing with article deadlines and dentist’s appointments and chores that always needed doing.

And then I found a quote by the memoirist Annie Dillard, from her book The Writing Life, that stopped me in my tracks. “How we spend our days,” she writes, “is of course how we spend our lives. What we do with this hour and that one is what we are doing.”

If I wanted to live a more adventurous life, I realized, I would have to plan to take adventures. If I wanted to make sure that I was enjoying my life, I would have to make sure it was filled with enjoyable things. And I needed to do it now: not after I bought a house, or made six figures, or landed my dream job, or had my kids. Now.

Rhythms

So I made my little list for the summer, and as I checked the items on it off one by one, I documented my adventures on Instagram for my friends to see. Some things went exactly as planned: a trip to the Stratford Festival to see the musical Something Rotten; a hike and picnic with Taylor at a nearby conservation area we had never visited before.

Other items on the list encouraged me to be more spontaneous, like when I tagged along on Jillian’s family trip to Canada’s Wonderland one weekend so I could ride rollercoasters. Seemingly simple tasks led to dramatic misadventures: Taylor and I took a short ride in a rowboat while visiting his parents in Wisconsin, and I accidentally tipped the boat and dumped him into the lake, prematurely ending both our excursion and the life of his cellphone.

By the time September rolled around, I had been to my first drive-in movie and brought down the house singing Train’s “Drops of Jupiter” at karaoke. But something else I hadn’t expected happened, too: I was chatting on Instagram with dozens of people, some of whom I hadn’t spoken to in years, about my current and future adventures. A lot of them had the same question, one I already knew the answer to: will you be making a new list for fall?

Despite the fact that I was going to New Zealand for almost three weeks in October, I planned another list full of autumnal plans, and I checked every one off. I went camping. I read Misery, my first-ever novel by Stephen King. Taylor and I went for an evening walk and took photos on disposable cameras that looked like childhood memories.

One sunny weekend right before we left for New Zealand, Jillian’s sister Jenna came to visit, and we checked off a record number of items in one day: exploring a corn maze, visiting an apple orchard, mulling cider, watching When Harry Met Sally. “I’m so thrilled that I get to be part of the list!” Jenna exclaimed as she took a quick video of me picking an apple and grinning.

By the time I made my list for winter, it felt like my seasonal bucket lists had taken on a life of their own. Close friends and distant acquaintances told me they were inspired to make their own seasonal or annual lists. I scheduled group plans weeks in advance to make sure I’d check off more difficult items. This week, despite being incredibly busy, I blocked out hours of time to make sure I could finish the last item on my winter bucket list (“finish a 600+ page novel”) before the official end of the season.

Sometimes, unfortunately, I lost sight of why I had started this project in the first place. The list began to stress me out: I was performing for an audience, adding items to an already long to-do list. “Put on your coat,” I brusquely ordered Taylor one Sunday afternoon last month. “We’ve got a free half hour and we have to make a snowman.”

And yet, despite the fact that I sometimes approached the items on my bucket list as obligations, they still fulfilled their purpose. They forced me to slow down, to breathe deeply, to notice the particularity of each season. In the past year, I’ve basked on a sunny beach and gone snow-shoeing, attended a rugby game and made candy with maple syrup and freshly fallen snow.

My bucket lists have become not a grand set of plans in the face of my imminent death, but rather an ongoing spiritual practice of noticing and honoring the much smaller births and deaths that make up our daily lives: the death of the roses growing along a neighbor’s fence, the death of the lemonade stands and yard sale flyers stapled to utility poles, the creation and drawn-out, welcome death of the enormous hills of frozen snow that litter the Giant Tiger parking lot next to my apartment building.

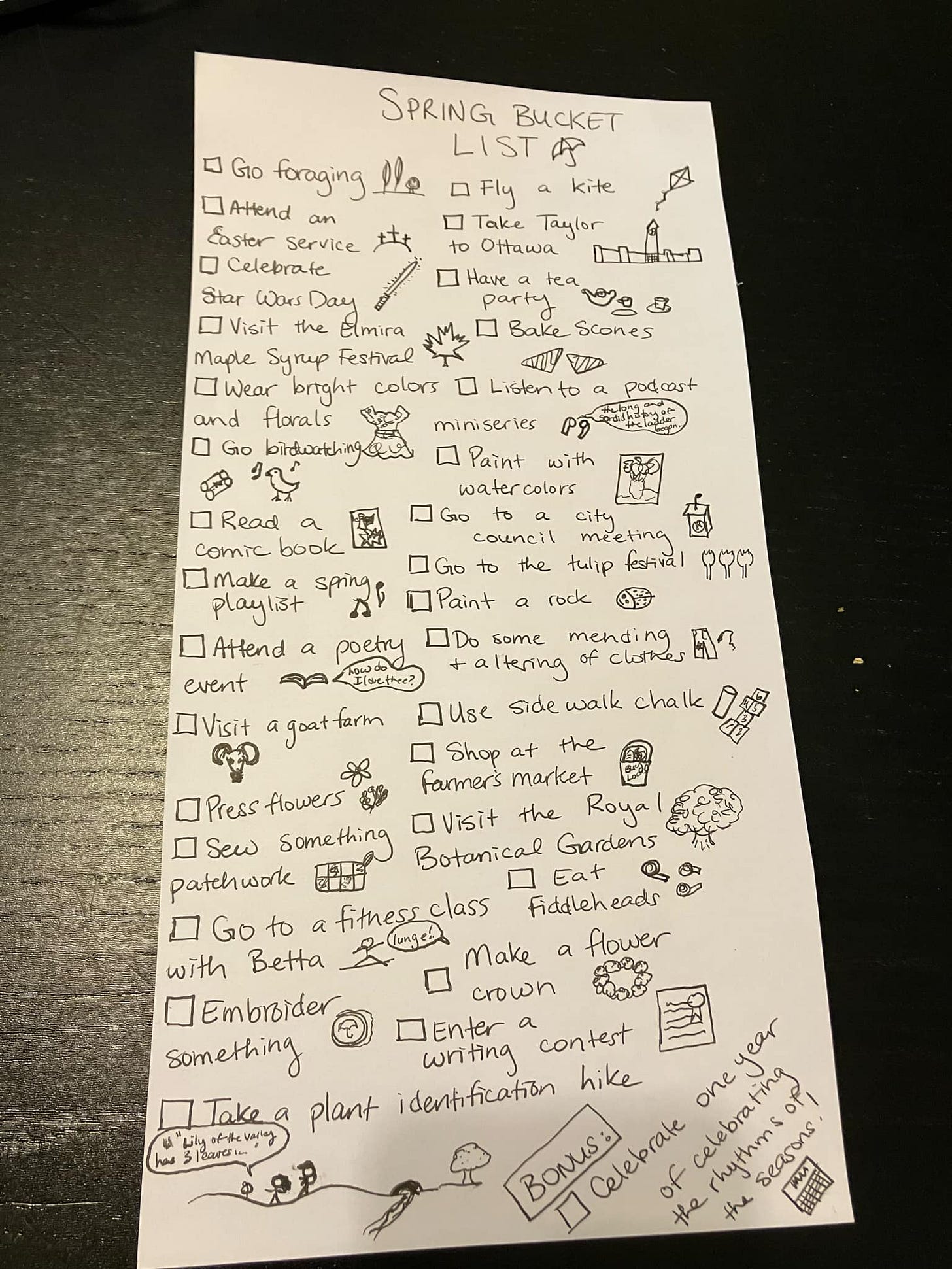

And now, with the first day of spring (and its accompanying list, of course!): the eager anticipation of wild leeks in the woods, and chalk drawings on the sidewalks, and the return of the mourning doves that coo softly at dawn and at twilight.

In his satirical novel The Screwtape Letters (1942), C. S. Lewis imagines a veteran demon advising his nephew on how to tempt humans away from the “Enemy,” (God). In one letter, Screwtape discusses his particular distaste for the cycle of the seasons:

“The horror of the Same Old Thing is one of the most valuable passions we have produced in the human heart—an endless source of heresies in religion, folly in counsel, infidelity in marriage, and inconstancy in friendship. The humans live in time, and experience reality successively. To experience much of it, therefore, they must experience many different things; in other words, they must experience change. And since they need change, the Enemy (being a hedonist at heart) has made change pleasurable to them, just as He has made eating pleasurable. But since He does not wish them to make change, any more than eating, an end in itself, He has balanced the love of change in them by a love of permanence. He has contrived to gratify both tastes together on the very world He has made, by that union of change and permanence which we call Rhythm. He gives them the seasons, each season different yet every year the same, so that spring is always felt as a novelty yet always as the recurrence of an immemorial theme. (74)

In a dissatisfied, consumerist culture that puts out Easter decorations in January, my seasonal bucket lists have grounded me in the present. In an individualistic world that tells us to always focus on self-improvement and self-interest, they’ve connected me to communities near and far. I’ve become a little better at prioritizing joy for its own sake. I’ve spent more time dancing to the rhythms.

“Oh my God,” writes Anne Lamott, in a 2014 Facebook post:

…what if you wake up some day, and you’re 65, or 75, and you never got your memoir or novel written, or you didn’t go swimming in those warm pools and oceans all those years because your thighs were jiggly and you had a nice big comfortable tummy; or you were just so strung out on perfectionism and people-pleasing that you forgot to have a big juicy creative life, of imagination and radical silliness and staring off into space like when you were a kid? It’s going to break your heart. Don’t let this happen.

When it comes to bucket lists, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

Also featured on this whiteboard are a limerick by the comic poet Ogden Nash, a list of book adaptations I watched, and a weird little poem I made up that has nothing to do with the looming Great Recession of 2008 and everything to do with my teenage desire to lose weight. I weighed 120 lbs at the time.

The explanation as to why is too long for a footnote, but it involves the tragic loss of a pink tasseled bicycle with training wheels, getting laughed at by my crush, and multiple injuries involving a bike chain.

Wait, should I add an OED citation to my bucket list?

I love following your progress on your lists! It’s great to learn more backstory.

Seriously one of my favorites!! I need/want to make at least one list before I kick the bucket.