Song of the Week: “Quiet,” by MILCK - “I can’t keep quiet for anyone anymore.”

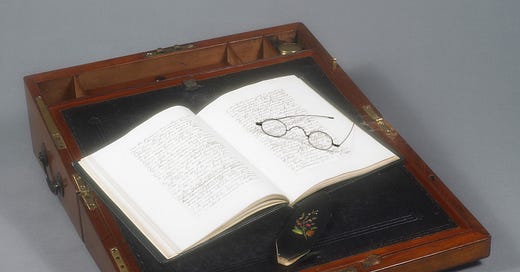

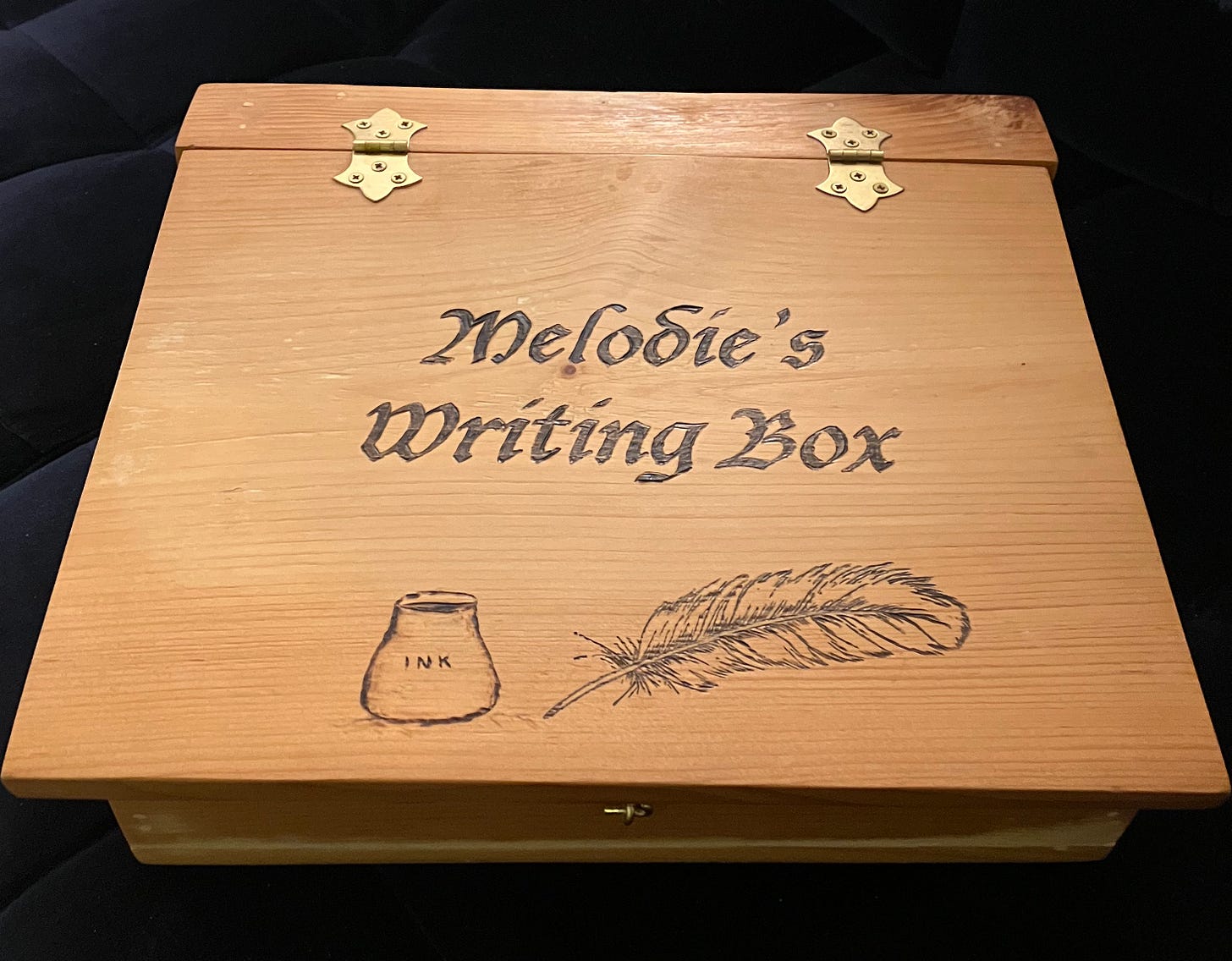

For my tenth birthday, my mom and grandpa built me a lap desk.

I don’t remember, now, whether it was a surprise or whether I watched them make it, but I can see them in my mind’s eye: my grandfather picking out aromatic wood at Home Depot, cutting the pieces to size and smoothing them with sandpaper, attaching hinges and a small metal hook, rubbing in stain with a rag to emphasize the texture of the wood grain. My mom painstakingly lining it with velvet, and then woodburning into the lid a quill and ink pot below the words “Melodie’s Writing Box.”

It was a beautiful gift, one that reflected not only craft and care but also belief: belief in my dreams of being a writer, and belief that writing was something appropriate for a little girl to dream of.

Years later, while I was working on my master’s degree in English, my best friend gifted me with a hand-drawn collage labeled: “Great Women of Lit.” It featured portraits of writers including Jane Austen, Louisa May Alcott, Maya Angelou - and, smack dab in the middle - me.

I don’t know how to measure the impact it has had on me, as a woman and a writer, to encounter nothing but encouragement and support throughout my life from the people who matter most. What I do know is that my experience is a rare one - and one not shared by many of the other women in that collage.

Shakespeare’s Sister

Without a doubt, the most famous essay ever written about women’s writing is Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own [AROOO] (1929).12 In this feminist classic, which grew out of two lectures given at women’s colleges, Woolf explores women’s literary heritage. Why, she asks, do contemporary female writers have so few literary foremothers to look to for inspiration and guidance? Are women inherently less talented thinkers and writers than men? Are they just more interested in marriage and children than in philosophy, history, and literature?

Woolf dismisses these possibilities quickly and with the sarcasm and derision they deserve. Rather, she argues, for much of history women have lacked those essentials needed to thrive as writers: a room of one’s own, and five hundred pounds a year. In other words, financial independence and physical and social space. Woolf recalls how she had an aunt who died, and left her a life-changing gift of five hundred pounds a year for the rest of her life. “Indeed my aunt’s legacy unveiled the sky to me,” she writes (39).

Even if women do have this independence, however, Woolf acknowledges that they still face the immense challenge of loved ones - and a larger society - that doubt their talent or pressure them to give up their careers. Historically, women have often been barred from universities, coffee houses, and professional societies, not to mention government offices and professional positions.

Even when women did write - and this remains painfully true today - their writing was frequently dismissed as trivial, or sentimental, or suitable only for women and children, not serious literature at all. “What genius, what integrity it must have required in the face of all that criticism, in the midst of that purely patriarchal society, to hold fast to the things as they saw it without shrinking” (74).

In AROOO, Woolf draws particular attention to the poor and working class women of history, women who received very little education, who never learned how to read, who certainly never had an income and space of their own. We will never know what these women would have written, she reflects, but we can find traces of them.

When, however, one reads of a witch being ducked, of a woman possessed by devils, of a wise woman selling herbs, or even of a very remarkable man who had a mother, then I think we are on the track of a lost novelist, a suppressed poet, of some mute and inglorious Jane Austen, some Emily Brontë who dashed her brains out on the moor or mopped and mowed about the highways crazed with the torture that her gift had put her to. Indeed, I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman. (49)

Woolf imagines one such woman: a sister to William Shakespeare. Shakespeare’s sister, she argues, would have all of his talent, but none of his opportunities. Instead of being educated, her parents would call upon her to peel potatoes or mend clothes when she wanted to read or write. When she ran away to London, she would be turned away from the stage and preyed upon by opportunistic men. Shakespeare’s sister, Woolf concludes, would end up pregnant, desolate, and alone, dying by suicide and buried “at some cross-roads” in an unmarked grave (48).

Notebooks on Laps

Though Woolf invokes her example throughout AROOO, Jane Austen had neither a room of her own nor 500 pounds a year for her own spending. She never married, her family struggled financially throughout much of her life, and she never lived alone. She wrote most of her novels in gasps and starts, in small notebooks she held on her lap while in the family drawing room, that she could conceal whenever someone came in.

Austen was, however, fortunate enough to have the love and support of her siblings - who worked to publish Mansfield Park and Persuasion after she died. She also had some high-profile fans like the Prince Regent while she was alive, despite the fact that her novels only identified their author as “A Lady.”

In her wonderful essay “‘The Real Mr. Darcy’: A Literary Pilgrimage,” Constance Grady discusses her trip to the very touristy Jane Austen Centre in Bath, UK. When I was in Bath in 2018, I walked across town to visit the Jane Austen Centre, only to discover it was closed. According to Grady, I didn’t miss much. The real treasure, she argues, is elsewhere:

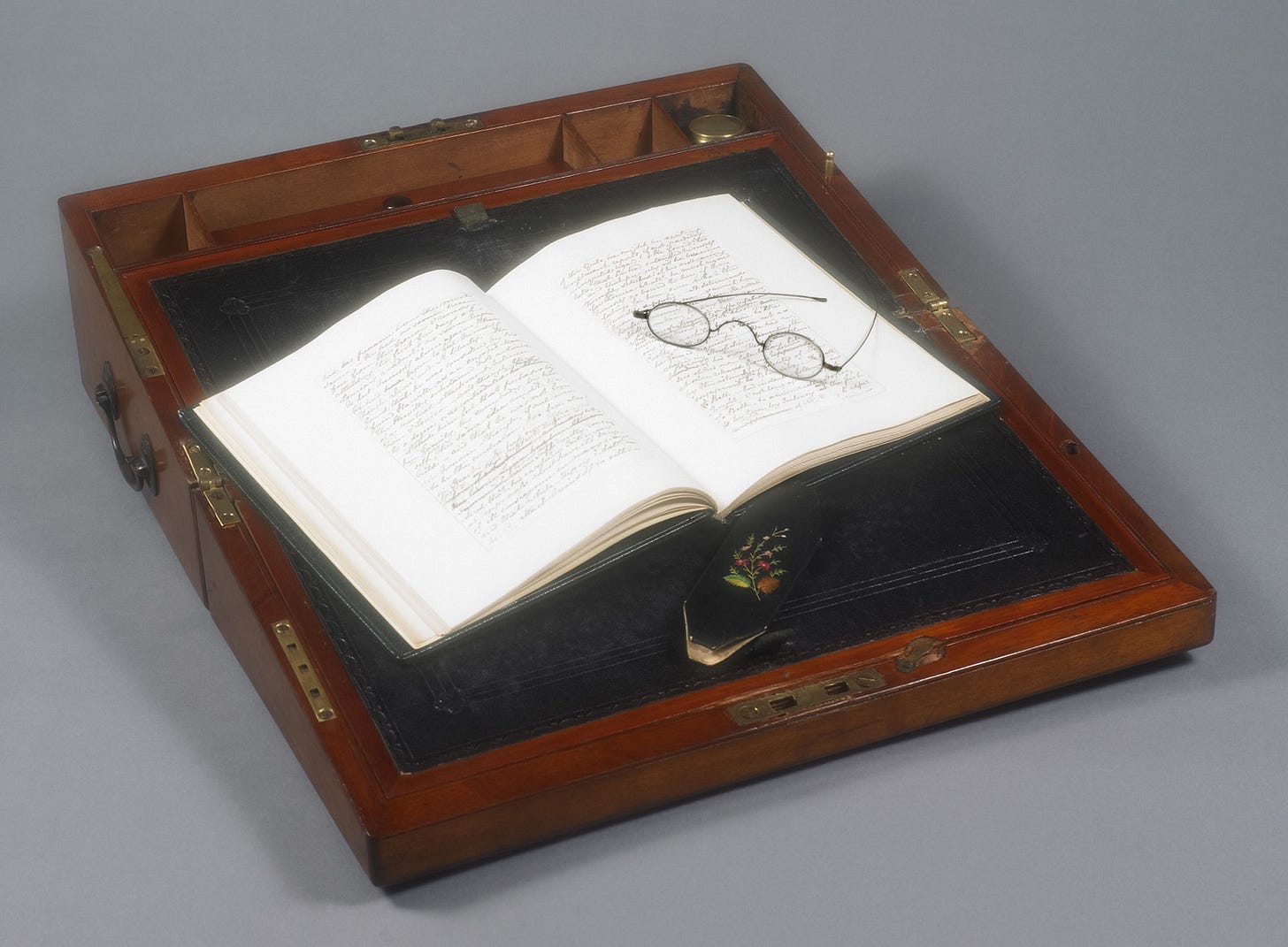

To see Jane Austen’s writing desk, you have to go to the British Library in London. It’s in a glass case in their Treasures of the British Library display, across from one of Shakespeare’s folios and a few cases away from some Beatles sheet music. It is a very small desk, and foldable, designed to be easily stowed away, which it must have been often; Austen wrote in her parlor and would hide her writing whenever callers stopped by. At the British Library it is open, with very small spectacles pinned to one corner and the tiny notebook that held the first draft of Persuasion lying on top of it, splayed flat so you can see Austen’s fine, precise handwriting. Under the shadow of that desk, the disciplined confinement of her novels acquires visceral force. This much space was she permitted, and no more.

In the display case next to Austen’s desk is Dickens’s first draft of Nicholas Nickelby, in a notebook that dwarfs Austen’s entire desk, with generous margins and looping, scrawly handwriting. It is impossible for me to imagine what Austen might have done with that kind of freedom, that kind of certainty of her own right to take up space.

Unlike the Jane Austen Centre, I have been to the British Library twice, and both times I have paid homage to Austen’s writing desk.

Grady leaves out one detail, by the way, about that writing desk, which I find especially poignant: it was a gift from her father.

Forgotten Voices

During my PhD, I took a class on Romantic-era British woman writers, motivated by frustration with modernist novels and my enduring love of Jane Austen. Alongside Pride and Prejudice and Northanger Abbey, we read an array of texts by women I had never heard of, including Anne Lister, Maria Edgeworth, and Phebe Gibbes. In some cases, it was clear why Austen’s work has endured while her peers faded into obscurity: for one thing, in an era without modern editors, she wrote brilliant prose marked by an economy of wit.

In other instances, however, I was moved by the kinship I felt with these female writers who have been condemned to obscurity. Some of them were queer. Many of them were not wealthy. All of them dealt with societal and personal obstacles to agency and success.

I did not realize, until I took that class, that the poet William Wordsworth had a sister, Dorothy. In her Grasmere and Alfoxden Journals, Dorothy intersperses anxieties about expenses, descriptions of menial household chores, and accounts of her brother’s frequent illnesses with flashes of insight and beauty. On one page, we get Dorothy’s own description of the famous daffodils: they “tossed & reeled & danced & seemed as if they verily laughed with the wind that blew upon them over the Lake, they looked so gay ever glancing ever changing” (85). A page later, she returns to her chief employments: copying out her brother’s poetry more neatly, and asking their friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge for money.

Wordsworth’s money troubles pale in comparison to those experienced by Charlotte Smith, the author of novels including Desmond (1792), which looks favorably upon the politics of the French Revolution. When she was 15 years old, Smith’s father married her against her will to Benjamin Smith, a violent man and compulsive gambler. Four decades later, Smith complained that her father had made her a “legal prostitute.”

The couple had twelve children, only six of whom outlived their mother. Benjamin was so financially irresponsible that he ended up in debtor’s prison; Charlotte moved into the prison with him, wrote a book called Elegiac Sonnets while living there, and paid their way out with the profits from its success. As her husband, Benjamin had the legal right to all of the money from the sales of her work, creating a pattern that endured for years: he fell into debt, Charlotte wrote their way out, and then the cycle repeated using her earnings for fuel.

There is always much talk, when speculating about time machines, about what action one would take to change history - killing baby Hitler, stopping the JFK assassination, and so on.

Me? I would go back to 1765 and rescue 15-year-old Charlotte. Imagine what she might have written, with a room of her own.

Even with these obstacles, however, the women we studied in my Romantic Women Writers class still had many privileges: they were white, they were educated, and they lived in one of the most powerful countries in the world.

The same semester that I was taking that class, I was also taking a class on feminist theories. In that other class, we read Gayatri Spivak’s famous essay “Can the Subaltern Speak?”

In this foundational piece of post-colonial criticism, Spivak considers the position of the “subaltern” - a term she borrows from the military. Spivak’s “subaltern” is a person who occupies the most marginalized position in society, silenced and oppressed by the powerful on all sides. The most famous example she gives is that of low-caste Indian widows, forced by their own people to burn on their husbands’ funeral pyres, and both ignored and abused by British colonizers at the same time (93). What can we know, she asks, of the dreams and desires of these women? “One never encounters the testimony of the women’s voice-consciousness,” Spivak writes. “As one goes down the grotesquely mistranscribed names of these women, the sacrificed widows, in the police reports included in the records of the East India Company, one cannot put together a ‘voice’” (93).

Though Spivak uses the specific case of these burned widows - which she explores in great detail for several pages - she applies her concept of the subaltern to people across nations and times. There are some people, she concludes, whose thoughts were never transcribed, who were so thoroughly silenced, that we will never be able to incorporate them into our record-keeping. Their voices are lost to history.

A Silent Home, Just to Herself

Mexican-American writer Sandra Cisneros’s semi-autobiographical novella The House on Mango Street (1984) uses a series of vignettes to illuminate a working-class Spanish-speaking neighborhood in Chicago, and a young girl named Esperanza (“hope”) who lives there. As Esperanza goes through puberty, she encounters the grinding impacts of poverty, grapples with her parents’ and neighbors’ disappointed dreams, and watches as girls her age are sexually objectified, assaulted, and often married off in their teens. Esperanza wants many things - money, glamor, sex, family, home - but she also lives in constant dread of the ways that these desires might betray her and trap her in the same cycles of violence and poverty that she watches so many of her neighbors inhabit.

At the end of the novel, driven equally by fear of and love for her neighborhood, she resolves to leave to pursue her dream of being a writer.

One day I will pack my bags of books and paper. One day I will say goodbye to Mango. I am too strong for her to keep me here forever. One day I will go away.

Friends and neighbors will say, What happened to that Esperanza? Where did she go with all those books and paper? Why did she march so far away?

They will not know I have gone away to come back. For the ones I left behind. (110)

The promise that Esperanza makes, Cisneros kept. In the introduction to my copy of The House on Mango Street, “A House of My Own,” Cisneros describes the apartment she lived in as a young writer. It was freezing cold, shabby, and in a bad part of town - and it was hers, and hers alone: “as a girl, she dreamed about having a silent home, just to herself, the way other women dreamed of their weddings” (xii).

Cisneros tells us that she worked stubbornly towards this dream, ignoring her father’s pressure to settle down and get married, and her own feelings of being an imposter, without any knowledge of potential literary foremothers. She wanted a room of her own, she says, without having yet read Virginia Woolf. She wanted to be a writer without having read any of her Latina foremothers or contemporaries: Sor Juana Inéz de la Cruz, Rosario Castellanos, Gloria Anzaldúa, Cherríe Moraga (xv).

Cisneros achieved a room of her own through a mixture of stubbornness and love: an insistence on the validity of her dreams, and a deep love for stories. She did it for her brilliant mother who only received a ninth grade education, and for the ones whose voices might be forgotten otherwise, out of a belief that “art should serve our communities” (xvii). And she did it for herself: for the stubborn little girl she had been, and the independent woman she wanted to be.

In the Flesh

Nineteen years after my grandfather and mother gifted me that writing desk, I gave myself a gift: a tattoo of a fountain pen on my right forearm. I paid for it with money I made writing.

When I posted a photo of my new tattoo on Instagram, I captioned it with the passage from A Room of One’s Own that I quoted above, about lost novelists and suppressed poets. But today, looking at that tattoo again as I finish this essay, I am reminded of the privilege I have to write, and the weight of the debt I owe to my foremothers, literary and otherwise.

“Now my belief,” Woolf concludes, returning once more to the image of Shakespeare’s sister, “is that this poet who never wrote a word and was buried at the crossroads still lives. She lives in you and in me, and in many other women who are not here tonight, for they are washing up the dishes and putting the children to bed. But she lives; for great poets do not die; they are continuing presences; they need only the opportunity to walk among us in the flesh” (113).

When it comes to “a room of her own”, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

What sound does a Woolf make? Arooooooo

Shortly after my local Indigo bookstore remodeled to devote more square footage to gifts and home goods, they featured a shopping area titled “A Room of Her Own.” It contained yoga mats, silky pajamas, scented candles, fashion accessories, twinkle lights, and absolutely no books.

Inspiring, Melodie! Quite sad about the Indigo bookstore remodelling.

That was very compelling. Many things I’d never heard before, and beautifully written, Melodie.