Song of the Week: “A Musical,” from Something Rotten! - “Out of nowhere, he just starts singing?”

By season six of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, things have taken a dark turn. What had started as a bright and quippy show about a 90s Valley Girl and her friends fighting vampires, demons, and monsters has quickly become an exploration of grief, guilt, and mortality.

The superpowered Buffy Summers is depressed and self-isolating from her friends, who can’t figure out how to communicate with her or each other. Romantic relationships are fraying or struggling to begin. And then, one day, for reasons no one in town can understand, everyone begins to sing. Some of the songs are practical vehicles for plot, such as in this scene where the cast speculates about what is causing these unexpected musical interludes.

But the most important moments in the episode “Once More With Feeling” are the ones where characters burst into song because their emotions have become too powerful to suppress. Unable to hide their feelings any longer, they confess love and doubt, despair and devotion - often accompanied with playful choreography!

While Buffy’s musical episode is explained away by a showbiz-loving demon, most musicals - whether on stage or on screen - provide no such explanation as to why characters suddenly burst into song. Sure, a disproportionately large number of musicals are about musicians and performers, but many of them are not. The characters in Les Miserables, Wicked, and Hamilton don’t often acknowledge that they’re singing. So why do they?

Simply put, characters in musicals sing for the same reason Buffy and her friends do, demon or no demon: because their feelings are too big to be contained by mere words. Musical theater scholar Katie Birenboim calls this the “hierarchy of expression”: “when you can’t speak anymore, you sing, [and] when you can’t sing anymore, you dance.” Rather than attempting to convey the sense of realism pursued by much non-musical theater or film, Birenboim argues, musicals embrace a larger-than-life emotional realism. “I think leaning into what a musical inherently is,” she concludes, “even embracing what some might see as the ‘weirdness’ or ‘fake’ aspect of musical theatre, makes for more interesting, exciting and groundbreaking art.”

One of my favorite recent projects to embrace that weirdness isn’t a stage show or movie, but rather a podcast: the improvised musical show Off Book, starring Jess McKenna and Zach Reino. In each episode, Jess, Zach, and a guest spontaneously create a comedic musical on a random theme, such as small town baseball or a “train corruption” court case. It’s always funny, and sometimes actually results in genuinely good songs. More than anything, however, the show just reminds me how much I love musicals in all their strange, over-the-top, genre-defying glory.

Tradition!

Last summer, Taylor and I went to see Something Rotten! at the Stratford Festival. Set in 1595 London, the show is a loving send up of both Shakespeare and musical theater. Struggling theater runner Nick Bottom is jealous of rockstar William Shakespeare, and visits a soothsayer to find out what the next big thing will be after Shakespeare’s comedies, tragedies, and history plays. Looking into the future, the soothsayer predicts the blockbuster success of musicals, and Nick sets out to create one and steal the crowds away from Shakespeare.

While Something Rotten!’s narrative of the transition from Shakespearean drama to musicals is a neat (and hilarious one), it’s also deeply simplified. The real story, as usual, is far more complicated.

As John Kenrick’s Musical Theatre: A History explains, contemporary musicals can be traced back to ancient Greek drama, which featured both spoken dialogue and musical comment provided by a chorus.

When Renaissance artists looked to the Greeks for inspiration, they mistakenly believed that the plays were entirely sung. “In the 1570s,” he writes, “this error led Monteverdi and a group of artists known as the Florentine Camarate to use Greek drama as the model of the first grand operas. So, instead of musical theatre being a descendant of opera, it turns out that opera is actually a descendant of musical theatre.”

Kenrick traces the development of numerous theatrical forms through the 1500s to the 1900s, including British ballad operas and music hall shows, racist American minstrel shows, German singspieles like The Magic Flute (1791), and forms of dance ranging from ballet to vaudeville and burlesque.

He points to the 1866 Broadway show The Black Crook as the first show that combined many of these pre-existing elements together in a form that would be recognizable to modern audiences. The wildly successful show, which ran in revivals and toured across the country for more than thirty years, was a happy accident. A theater was adapting a contemporary fantasy novel, and the director was uninspired by the result. When a visiting ballet company’s host theater burned down, he suggested they join forces, resulting in an all-singing, all-dancing special effects extravaganza that wowed audiences.

Early musicals tended to be both comedic and sentimental, with wacky plots, a focus on romance, and guaranteed happy endings. Like modern jukebox musics built from existing pop songs such as Mamma Mia!, they often incorporated existing popular songs, or included barely-relevant musical numbers that only existed to show off an actor’s singing or dancing chops.

Then, in 1927, a young lyricist named Oscar Hammerstein II adapted a popular novel into a musical called Show Boat and changed musical theater forever. Show Boat is notable for a couple of reasons. First and foremost, it is a dramatic epic, taking place over decades and featuring heartbreak, disappointment, and a melancholy ending. As Mark Lubbock wrote in 1962, “Here we come to a completely new genre - the musical play as distinguished from musical comedy. Now…the play was the thing, and everything else was subservient to that play. Now…came complete integration of song, humor and production numbers into a single and inextricable artistic entity.”

In the 1940s and 1950s, Hammerstein would collaborate on dozens of musicals with composer Richard Rodgers, all of which shared Show Boat’s complete integration of plot, music, and characterization, including Oklahoma! (1943), Carousel (1945), South Pacific (1947), and The Sound of Music (1959).

Just as importantly, Show Boat featured a Black character who wasn’t there to provide racist comic relief. As I noted before, one of the major ancestors of the modern musical was the racist minstrel show: shows in which white actors wearing blackface performed comical skits and musical numbers mocking enslaved people and free Black people. The originator of the genre, 1820s entertainer Thomas Rice, called his character “Jim Crow.” By the early 1900s, some Black actors and musicians were putting on their own minstrel shows, but these productions were usually just as racist and stereotypical as the ones starring white actors. It would be more than fifty years before successful 1970s musicals like The Whiz (1974) centered Black creative visions on Broadway.

While the main plot of Show Boat is about a young woman who wants to be a stage performer, its most memorable character is Paul Robeson’s Joe, a Black riverboat laborer who has endured decades of racism. His spiritual-inspired showstopper “Ol’ Man River” is the highlight of Show Boat; I saw the musical live when I was 19, and it’s the only song I remember.

Show Boat also made headlines because of its integrated cast and interracial romance plot, both of which were unheard of at the time. While mainstream musicals would continue to struggle with explicit and implied racism for decades to come, Show Boat represents the first major attempt to use the musical as a vehicle for social critique and progressive reform.

Unfortunately, only two years after Show Boat’s premiere, the Great Depression Hit, and theaters started going bankrupt left and right. While the booming WWII economy would eventually bring patrons back to Broadway, in the meantime many of the most successful actors and musicians headed west to Hollywood to translate their art to the big screen.

No Business Like Show Business

As soon as silent films became talkies, they used their newfound sound to make musicals. The first sound film ever, The Jazz Singer (1927), is a musical starring Broadway sensation Al Jolson.1

Film’s strength compared to live theater was also its weakness: it was accessible and replayable. Rather than having a limited run in a theater where tickets were expensive and the experience ephemeral, movie musicals allowed fans to revisit a favorite show again and again. At the same time, diehards maintain, filmed musicals lack the immediacy and magic of live theater.

Throughout the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, Hollywood musicals were enormously successful, driven by the songwriting talent of Broadway creators and the star power of celebrities like Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers, and Judy Garland. Many film adaptations of existing properties like The Wizard of Oz (1939) and White Christmas (1954) became more enduringly popular than their stage counterparts.2

In the decades that followed, movie musicals remained financially successful even if they were often critically panned. Broadway superstars like Andrew Lloyd Weber and Stephen Sondheim saw not only success on stages both sides of the Atlantic, but also on the silver screen, with movie adaptations like West Side Story (1961) and Jesus Christ Superstar (1973) proving to be reliable box office hits.

In the twenty-first century, we’re in a new Golden Age of movie musicals: though some films such as Cats (2019) and Dear Evan Hansen (2021) have been notorious flops, others such as Moulin Rouge! (2001), La La Land (2016) and Wicked (2024) were enormously popular.

The 1930s also saw the introduction of a genre so successful that for many people it became synonymous with musicals as a whole: the animated Disney musical. Even as the popularity of movie musicals and Broadway shows waxed and waned throughout the twentieth century, Disney’s animated musicals provided the soundtracks for generations of childhoods. From classics like Pinnochio’s “If You Wish Upon a Star” (1940) and Sleeping Beauty’s “Once Upon a Dream” (1959) to contemporary chart toppers like Frozen’s “Let It Go” (2013) and Encanto’s “We Don’t Talk About Bruno” (2021), Disney songs have a life of their own.

While the success of Disney musicals stems from the labor of thousands of animators, actors, writers, and musicians stretching for almost a century, one composer stands out: Alan Menken. An accomplished composer who also created the Broadway hits Little Shop of Horrors (1982) and Newsies (2012), Menken wrote or co-wrote a staggering number of Disney musicals: The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Pocahontas (1995), The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996), Hercules (1997), and Tangled (2010).3 Unsurprisingly, he is one of a tiny group of people who have achieved an EGOT: he has won an Emmy, a Grammy, an Oscar, and a Tony.

Despite Menken’s enormous success, he isn’t afraid to poke fun at himself and his style either. In Enchanted (2007), Menken’s score takes us from a picture-perfect animated film to a live-action New York, where Disney princess Giselle sings to rats and cockroaches instead of woodland creatures.

And in the criminally underrated musical TV series Galavant (2015-2016), Menken gives us episode after episode of musical numbers that satirize not only Disney movies but also musical theater, high fantasy, and prestige television more broadly.

Menken’s work is often overlooked by critics because he writes primarily for children, but he doesn’t mind. He doesn’t even see himself as a composer of children’s music. “I never write for kids,” he says in a 2008 interview. “I write for me. I write for myself. I want to tell a story. I want to make those kids feel like I felt when I saw those earlier movies.”

My Favorite Things

Growing up Seventh-Day Adventist, there was one musical that stood above all the rest: The Sound of Music.

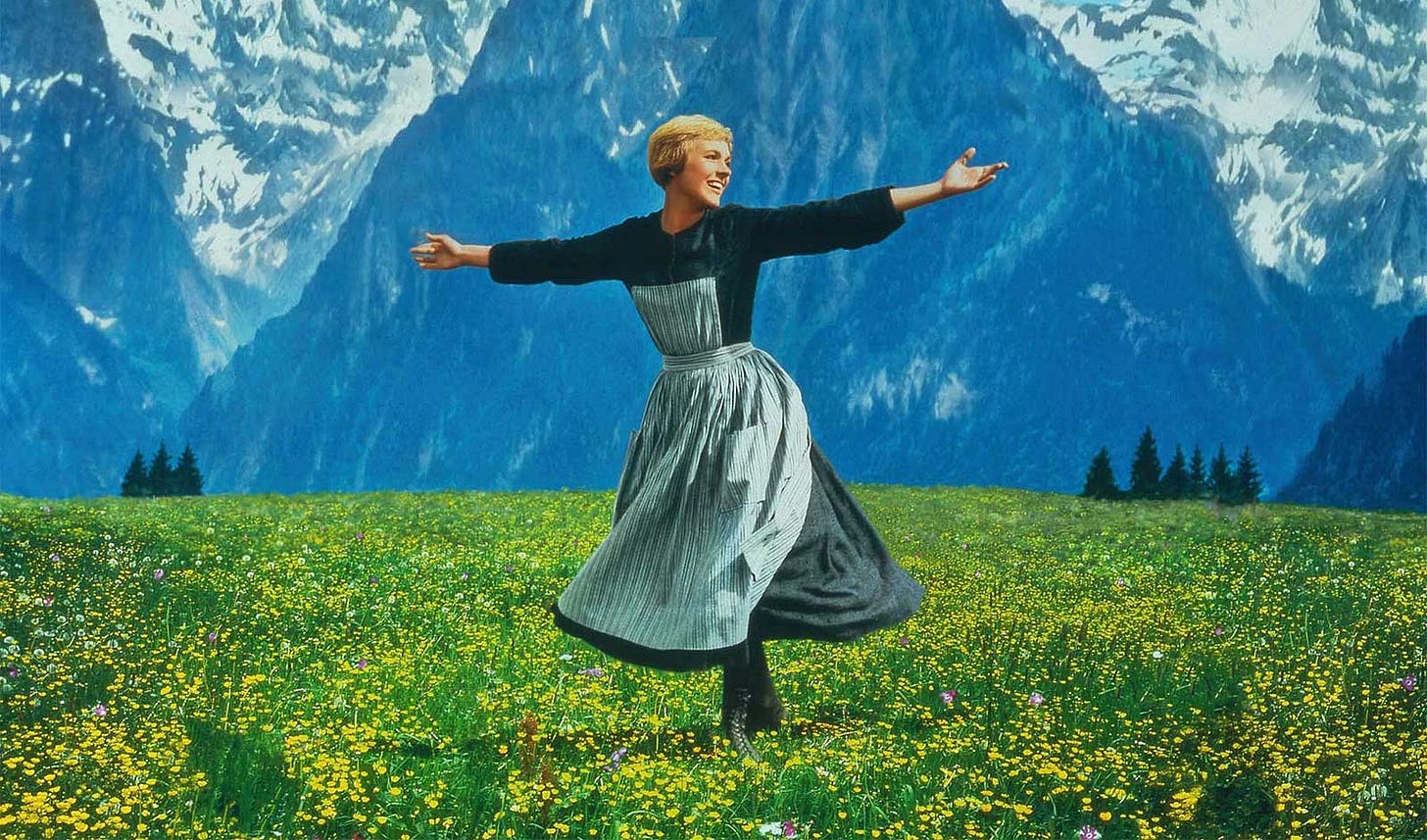

The Sound of Music needs no introduction: based loosely on the true story of the Von Trapps, a musical family that fled Austria following the Nazis’ takeover, it was adapted by Rodgers and Hammerstein into a successful musical in 1959, then into a film starring Julie Andrews in 1965. While The Sound of Music is regarded as a wholesome, sentimental story by the general public, for contemporary Adventists it is a foundational text.

As Adventist professor (and my beloved student newspaper sponsor!) Dr. Scott Moncrieff reflects in his book Screen Deep: A Christian Perspective on Pop Culture (2007), “The Sound of Music is at the heart of Adventist cultural literacy…It is the film we all hold in common” (80).

Traditionally, Seventh-Day Adventists didn’t attend movie theaters; my mom didn’t visit one until I was a teenager. To get around this prohibition, in the 1960s onward many Adventist high schools and universities hosted sold-out fundraiser screenings of the film. My mom remembers her family driving from Ontario to southwest Michigan to visit her sister at Andrews University - and, thrillingly, catch a screening of The Sound of Music that evening in Johnson Gymnasium. Years later, one of her sisters used the film’s wedding music as her own processional march!4

As Moncrieff explains, the film has multiple appeals for Adventist viewers: beyond its family friendly wholesomeness, the film’s central themes of deep religiosity and escaping persecution resonated deeply with Adventists. Like most Adventists raised to expect the end of the world, Moncrieff reflects, “Fleeing to the hills was part of the topography of my imagination” (83). Sure, The Sound of Music features Catholics fleeing Nazis instead of Adventists fleeing Catholics, but the plot still translates neatly.

Not all Adventists, of course, love The Sound of Music so deeply. I’ll never forget the rant that my boss, Professor Gary Gray, went on one afternoon while I was organizing the bookshelves in his office. “The Sound of Music,” he fumed, albeit with a twinkle in his eye. “I’ll tell you what. Women don’t want nice boys, they want Austrian naval captains.”

When he was newly Adventist and a university student, he explained, his girlfriend at the time asked him to accompany her to a screening of The Sound of Music at (where else) the school gym. He didn’t get the appeal, but she - and the rest of the audience - were rapt.

Midway through the film, the soundtrack briefly stopped working. “And what did these people do?” he scoffed. “They started singing all the songs themselves until it was fixed!”

Shortly after the screening, Prof. Gray’s girlfriend broke up with him. He begrudgingly admitted that the relationship had already been on the rocks, but “I’m telling you, that Christopher Plummer was partly to blame!”

Professor Gray would be comforted, perhaps, to learn that Christopher Plummer agreed with his take on The Sound of Music. Plummer, who plays the dishy Captain Von Trapp, famously loathed the movie at the time, considering it cheesy and overdone. He even privately referred to it as “The Sound of Mucus”!

That being said, his attitude changed over the years; at the film’s fiftieth anniversary screening in 2015, Julie Andrews recalled: “He started out of love and fell in love. He very quickly realised that it was so well crafted and so well done. In fact, he’s been wonderful about it for many years.” When Plummer died in in 2021, it was a gif of his appearance in The Sound of Music that went viral: one of him tearing up a Nazi flag.

Unsurprisingly, The Sound of Music was also central to my Adventist experience. I grew up loving the film and watching it with my cousins, and was thrilled in high school when our drama club decided to put on a production. The choir and band were conscripted for accompaniment, and the casting call was attended by students from across the school. Nine girls auditioned to play “16-going-on-17” Liesl, including yours truly.

Unfortunately for me (and several other aspiring Liesls), we - like many other high school theater programs - severely lacked male actors, and I was cast not as the beautiful Liesl but as Admiral von Schreiber, a secondary Nazi villain who doesn’t even make it into the film.

In retrospect, I like to believe that this was at least partially because I worked for the drama teacher (who was also the math teacher) and ended up as the assistant stage manager as well. But still: what a blow to the ego! It’s probably for the best that filming and photography were banned as part of the licensing process, so my turn as von Schreiber is lost to history.

Nevertheless, we had a marvelous time. I sang in the choir, learned a scandalous waltz step to be part of the ensemble, and practiced informing Captain von Trapp that he had to “report to the naval base at Bremerhaven by the next morning.” Sets were built and painted, costumes were sewn, and an overly productive smoke machine was rented. Maria and the Captain perfected their duet, our diverse and enthusiastic cast grew close, and if in retrospect it might raise a few eyebrows to cast a Black student as the aspiring Nazi Rolf, we thought little of it.

The entire cast took a field trip to Toronto to see a touring production of The Sound of Music on stage, and came back with our eyes shining. We were like them: real performers.

The show was an enormous success. Parents and friends drove for hours to pack the auditorium for all three shows, giving us rave reviews. “You’ve made something really special here,” a prominent church leader told our director after the show. “You did The Sound of Music and the school proud.”

Even my ponytail tumbling down from beneath my hat during my one scene in the final performance couldn’t quash my high spirits. I’ll never forget the electricity we all felt when we took our choreographed bows at the end of each night. We were part of something ephemeral and wonderful and created by and for each other. We were transcendent.

Wrote My Way Out

For me, my stint in high school theater stayed just that. I did a bit more acting after The Sound of Music, including a groan worthy cowboy comedy and some selections from Moliére and Shakespeare in university, but I soon discovered that I was happier writing than acting (not to mention far more gifted!).

For many others, however, those first brushes with musical theater - whether it’s in a school production or a local community theater - are the beginning of lifelong dreams. That’s the sentiment shared by Neil Patrick Harris at the end of his rip-roaring opening number for the 2013 Tony Awards, “Bigger.”

“There’s a kid in the middle of nowhere who’s sitting there living for Tony performances,” he sings, “Singin’ and flippin’ along with the Pippins and Wickeds and Kinkys, Matildas, and Mormonses / So we might reassure that kid / and do something to spur that kid / ‘Cause I promise you, all of us up here tonight - we were that kid / and now we’re bigger!”

Or consider the exuberant opening number of La La Land (2016), a love letter to the Hollywood musical, in which strangers stuck in traffic sing about the inspiration behind their dreams of stardom:

“Some day as I sing a song,” one man imagines, “A small-town kid’ll come along / That’ll be the thing to push him on and go.”

It should come as no surprise that two of my favorite musicals are about writers. In the gorgeous Greek mythology-inspired Hadestown, Orpheus is obsessed with writing the song that will bring the spring back, and in the hip-hop American history musical Hamilton, Alexander Hamilton writes “like he’s running out of time.”

Last night I discovered a new favorite: I finally watched tick…tick…BOOM! (2021), a movie musical starring Andrew Garfield as Jonathan Larson, the creator of Rent (1996). Larson tragically died of an aneurysm at the age of 35 the night before Rent’s opening, and never witnessed its incredible impact on musical theater.

Director Lin-Manuel Miranda, however, focuses not on Larson’s most famous work, but rather on the process that he goes through attempting to produce an earlier satirical science fiction musical called Superbia, which never successfully reached the stage.5

As he approaches 30, Larson questions whether he should continue to create art and struggle to make ends meet, or settle for a comfortable but soulless career in advertising. His all-consuming focus on his art is hurting his relationships to others and leaves him constantly scrambling to pay the bills, but he knows that there is nothing else he would rather be doing. At the same time, he worries that his time is running out, and wonders whether he will ever leave behind a work of art worth remembering.

In my favorite song from the film, “Why,” Larson reflects on his childhood performances with his best friend, and the lifelong passion for theater they inspired in him. “Hey, what a way to spend a day,” he reminisces. “I make a vow right here and now / I’m gonna spend my time this way.”

Watching that scene on my laptop in bed, I unexpectedly started sobbing. Because I saw myself in Larson’s dreams, struggles, and questions: in the frustration and joy of the creative process, as well as the continuous tug-of-war between making practical decisions and spending your time in a way that makes you feel completely fulfilled and alive.

I’ll always love musicals: not only because they’re clever and well-crafted, beautiful and funny, but because they bring me back to myself when it seems like I’ve drifted away.

They’re not larger than life, exactly - but rather life on the scale that we feel it.

When it comes to musicals, what should I add to my syllabus?

I want to hear from you, whether it’s in the comments on this post or in emails to me directly at roschmansyllabus@substack.com!

As, it must be noted, a blackface performer. While the film is a valuable historical artifact, there isn’t much there that will be entertaining or moving to contemporary audiences.

At the same time, in India, Bollywood began making enormously popular film musicals and never let up. A parallel history of the musical’s development in Bollywood is beyond the scope of this essay, but it is a long and rich one!

In his earlier work, Menken frequently collaborated with Howard Ashman, who died tragically of complications from HIV/AIDS in 1991 at the age of 40. Beauty and the Beast is dedicated to Ashman: “To our friend, Howard, who gave a mermaid her voice and a beast his soul, we will be forever grateful.”

Minus the “How Do You Solve a Problem like Maria?” part, of course.

The film takes its title and music from a semi-autobiographical “rock monologue” called tick…tick..BOOM! that Larson performed in various forms throughout his career, but supplements it with additional biographical material.

I love musicals too. Thanks for the awesome clips, especially Neil Patrick Harris and Andrew Garfield!